Jannik Sinner just wrapped up a season for the ages. He won both hard-court majors, three Masters 1000s, and the Tour Finals. He led Team Italy to a Davis Cup championship and ended his campaign on a 26-set winning streak.

By November, the Italian was no longer competing against the field: He was gunning for a place in the record books. He went undefeated against players outside the top 20. Not a single player straight-setted him: He won at least one set in each of his 79 matches. Only Roger Federer, in 2005, had ever managed that.

After Sinner won the Australian Open, I wrote that Yes, Jannik Sinner Really Is This Good. Since then, he got even better. In the seven-month span ending in Melbourne, the Italian held 91.1% of his service games, a mark that not only led the tour but put him in the company of some of the greatest servers of all time. For the entire 2024 season, he upped that figure to 91.5%–including thirteen matches on clay.

He also defied the most powerful force in all of sport, regression to the mean. Sinner’s hold percentage was aided by some sterling work saving break points. He won tons of service points, of course, but he was even better facing break point. The average top-50 player is worse: Good returners generate more break points, so it’s a tough trend to defy.

In the 52 weeks ending in Melbourne, Sinner had won three percentage points more break points than overall service points. I wrote then: “I can tell you what usually happens after a season of break-point overperformance: It doesn’t last.” In the Italian’s case, though, it did. In 2024 as a whole, he won 71.1% of service points, and 73.6% of break points. He would have enjoyed a productive season without repeating his break-point overperformance, but those two-and-a-half percentage points explain much of the gap between very good and historically great.

Clubbable

Most players who serve so effectively are middling returners. The Italian has bucked that trend as well.

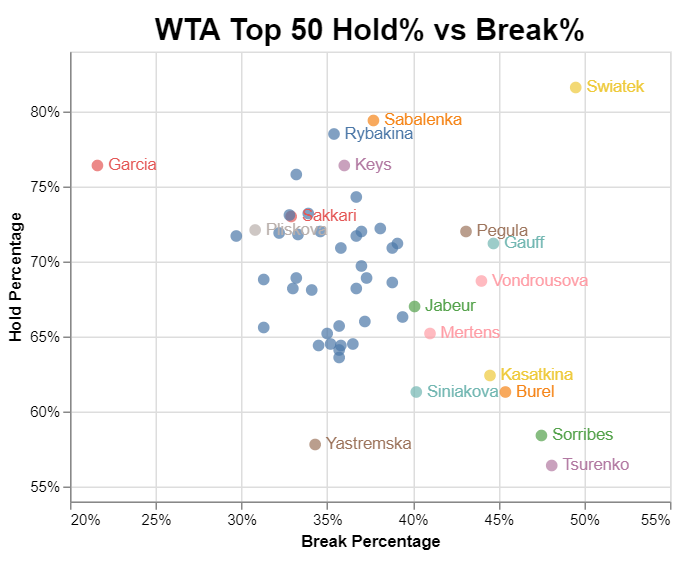

Late in 2023 I wrote about tennis most exclusive clubs–Alex Gruskin’s method for identifying standout players by their rankings in the hold and break percentage categories. It’s rare for anyone to crack the top ten in both. In 2023, Sinner signaled what was coming by finishing in both top fives. He ranked fifth by hold percentage and fourth by break percentage. Most seasons, that would have been enough for a year-end number one, but Novak Djokovic was even better, finishing in the top three on both sides of the ball.

Sinner, as we’ve seen, served even better this year. His 91.5% hold percentage was well clear of the pack, even with the resurgence of countryman Matteo Berrettini and increased time on tour from rocket men Ben Shelton and Giovanni Mpetshi Perricard. Last season, Djokovic led the tour by holding 88.9% of his service games. That’s impressive, especially for a guy known for other parts of his game, but it wouldn’t have cracked the 2024 top three. The Italian set a new standard.

At the same time, his return barely flagged. He fell out of the the top five by the narrowest of margins, winning nearly as many return games as he did in 2023 but falling to sixth place. Still, a “top-six club” showing is plenty rare. The only players who have posted one since 1991 (when these stats became available) are Djokovic, Nadal, Federer, and Andre Agassi. Federer only managed it once. Sinner has now done it twice.

The Italian’s return skills are even more impressive when we compare him the other season-best servers of the last thirty-plus years. The following table shows the hold-percentage leader for each year, along with his break percentage and his rank (among the ATP top 50) in that category:

Year Player Hold% Brk% Rank 1991 Pete Sampras 87.3% 25.4% 40 1992 Goran Ivanisevic 88.8% 20.4% 48 1993 Pete Sampras 89.6% 27.7% 19 1994 Pete Sampras 88.4% 29.3% 19 1995 Pete Sampras 89.0% 26.0% 25 1996 Pete Sampras 90.8% 20.8% 43 1997 Greg Rusedski 91.6% 16.7% 50 1998 Richard Krajicek 89.2% 21.4% 41 1999 Pete Sampras 89.7% 21.7% 44 2000 Pete Sampras 91.7% 18.4% 49 2001 Andy Roddick 90.4% 19.7% 45 2002 Greg Rusedski 88.5% 17.6% 48 Year Player Hold% Brk% Rank 2003 Andy Roddick 91.5% 20.9% 43 2004 Joachim Johansson 91.9% 14.5% 48 2005 Andy Roddick 92.5% 20.8% 45 2006 Andy Roddick 90.5% 22.4% 43 2007 Ivo Karlovic 94.5% 9.8% 50 2008 Andy Roddick 91.2% 19.2% 40 2009 Ivo Karlovic 92.2% 10.3% 50 2010 Andy Roddick 91.1% 17.6% 47 2011 John Isner 90.7% 12.9% 50 2012 Milos Raonic 92.7% 15.1% 49 2013 Milos Raonic 91.4% 15.7% 49 2014 John Isner 93.1% 9.3% 49 Year Player Hold% Brk% Rank 2015 Ivo Karlovic 95.5% 9.6% 50 2016 John Isner 93.4% 10.9% 49 2017 John Isner 92.9% 9.6% 50 2018 John Isner 93.8% 9.4% 50 2019 John Isner 94.1% 9.7% 49 2020 Milos Raonic 93.9% 18.0% 44 2021 John Isner 91.1% 8.8% 50 2022 Nick Kyrgios 92.9% 19.3% 40 2023 Novak Djokovic 88.9% 28.8% 3 2024 Jannik Sinner 91.5% 28.3% 6

If it hadn’t been for Djokovic’s appearance at the top of last year’s list, Sinner’s 2024 campaign would be hardly recognizable. Even Pete Sampras struggled to hold on to a spot in the break-percentage top 20. Circuit-best servers simply aren’t supposed to win so many return games, yet Sinner threatens to make it the new normal.

Carrot yElo

The Italian’s 73 wins, including 18 against the top ten, took his Elo rating to new heights. He began the year with a career-high rating of 2,197, second on the circuit to Djokovic. He quickly took over the top spot, ultimately clearing the 2,300 mark with his victory at the Tour Finals.

Elo is not a perfect measure to compare players from different eras, but in my opinion, it’s the best we’ve got. It’s the basis of my Tennis 128, which Sinner will join as soon as I get around to updating the calculations. 2,300 is rarefied air: In the last half-century, he is only the twelfth player to reach that mark. With three singles victories to secure the Davis Cup, he nudged his rating up to 2,309, surpassing Mats Wilander and establishing the eleventh-highest peak since the formation of the ATP.

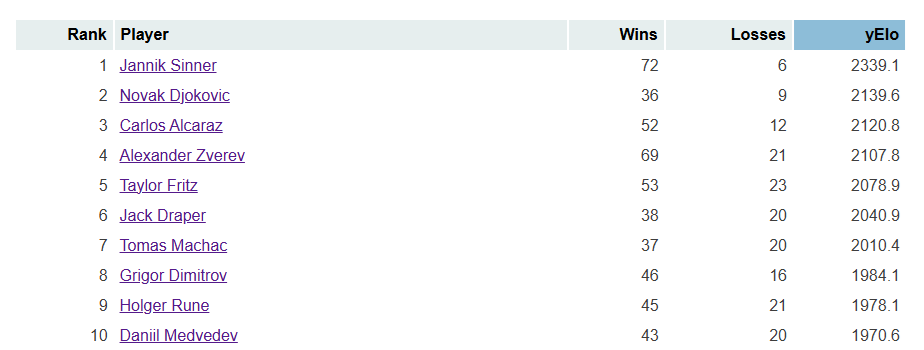

A stratospheric Elo is an indication of an outstanding player at the top of his game, but the metric is not designed to rate seasons. The alternative is yElo, a variation I devised for exactly this purpose. yElo works the same way as Elo does, adding or subtracting points based on wins, losses, and the quality of opposition. But unlike the more traditional measure, each player starts the season with a clean slate.

By regular Elo, Sinner holds a 150-point lead over second-place Carlos Alcaraz. By yElo, with its narrower focus, the Italian is even more dominant:

(The won-loss records are a bit different from official figures because my Elo and yElo calculations exclude matches that ended in retirement.)

The two-hundred-point gap between Sinner and Djokovic is one of the largest ever. Again going back to 1973, it ranks fourth. Only 2004 and 2006 Federer (over Lleyton Hewitt and Nadal, respectively) and 1984 John McEnroe (over Wilander) outpaced the competition by such a substantial margin.

By raw yElo, Sinner’s 2024 isn’t quite so historic. It’s the 26th best of the last half-century: An impressive feat, but not as close to the top of the list as some of the other trivia suggests. Here’s the list:

Year Player W-L yElo 1979 Bjorn Borg 84-5 2499 1984 John McEnroe 82-3 2476 2015 Novak Djokovic 82-6 2458 1985 Ivan Lendl 82-7 2440 2016 Andy Murray 78-9 2416 2013 Novak Djokovic 74-9 2408 1976 Jimmy Connors 97-7 2406 1977 Bjorn Borg 78-6 2403 1977 Guillermo Vilas 133-13 2401 2006 Roger Federer 91-5 2399 1980 Bjorn Borg 70-5 2395 1981 Ivan Lendl 96-12 2383 1987 Ivan Lendl 73-7 2381 1982 Ivan Lendl 105-9 2380 1978 Jimmy Connors 66-5 2379 Year Player W-L yElo 2013 Rafael Nadal 74-7 2373 1986 Ivan Lendl 74-6 2369 2011 Novak Djokovic 63-4 2367 2005 Roger Federer 80-4 2364 2014 Novak Djokovic 61-8 2363 2012 Novak Djokovic 73-12 2360 1978 Bjorn Borg 79-6 2359 2008 Rafael Nadal 81-10 2352 1986 Boris Becker 69-13 2347 1982 John McEnroe 71-9 2341 2024 Jannik Sinner 72-6 2339 1983 Mats Wilander 80-11 2338 1974 Jimmy Connors 94-5 2332 1989 Boris Becker 64-8 2329 2015 Roger Federer 62-11 2329

One factor holding back Jannik’s 2024 is the number of matches played. Elo, in part, reflects the confidence we have in a rating. Winning 90% of 100 matches (or almost 150, in the case of Vilas) gives us more confidence in an assessment than 90% of 80 matches.

Another issue is that Elo has opinions about strong and weak eras. Going 70-5 in 1980 doesn’t look much different than 72-6 today, but Elo considers Bjorn Borg’s peers to have been stronger than Sinner’s. If Sinner and Alcaraz continue to improve and a couple of their peers emerge as superstars in their own right, then a 72-6 season might rank much higher.

The asphalt jungle

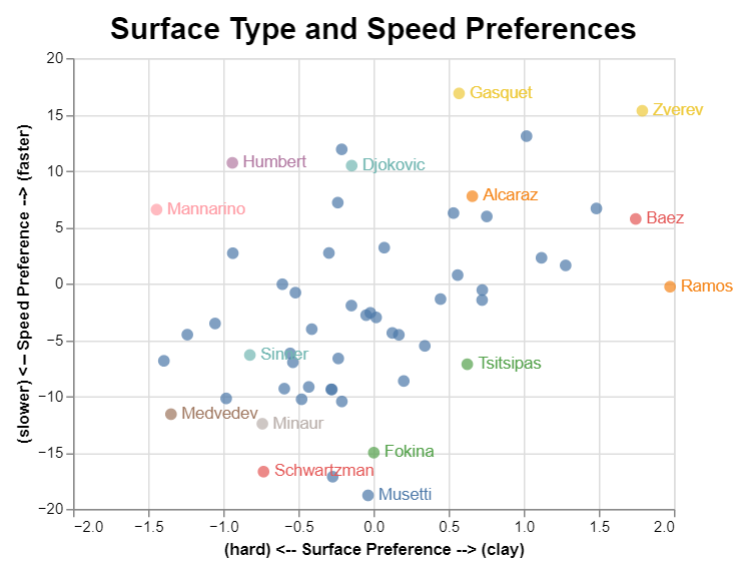

A couple of months ago, pundits started mulling where Sinner’s 2024 stood among the greatest hard-court seasons of all time. Since then, he piled on so many more wins that the qualifier wasn’t needed. Yet it remains a valid question.

The Italian’s highlights came almost entirely on hard courts. He won 53 of 56 matches, 42 of them in straight sets. He’s plenty skilled on natural surfaces, but given a predictable bounce and conditions that emphasize his power and penetration, opponents don’t stand a chance.

I don’t publish surface-specific yElo ratings, because they have limited usefulness for much of the year. For our purposes, though, hard-court yElo–same algorithm, limited to matches on one surface–is just the ticket. By this measure, Sinner’s 2024 is the eighth-best of all time:

Year Player Hard W-L Hard yElo 2015 Novak Djokovic 59-5 2426 2013 Novak Djokovic 53-5 2413 2012 Novak Djokovic 48-5 2377 2005 Roger Federer 49-1 2374 2006 Roger Federer 59-2 2373 1995 Andre Agassi 52-3 2370 2016 Andy Murray 48-6 2363 2024 Jannik Sinner 52-3 2353 2010 Roger Federer 45-7 2338 2014 Novak Djokovic 40-6 2334 Year Player Hard W-L Hard yElo 2014 Roger Federer 56-7 2333 1985 Ivan Lendl 29-3 2332 1987 Ivan Lendl 33-2 2325 1996 Pete Sampras 46-4 2319 2015 Roger Federer 38-6 2318 1981 Ivan Lendl 41-3 2317 2011 Roger Federer 45-7 2314 2009 Novak Djokovic 53-10 2309 1985 John McEnroe 25-1 2309 1986 Ivan Lendl 30-2 2298

So, um, peak Djokovic was pretty good, huh?

Even though Elo doesn’t hold the rest of the 2024 field in particularly high regard, Sinner’s season was so dominant that he does well by this measure. A year that would rate as Djokovic’s fourth-best, Federer’s third, or Agassi’s second, is truly something worth celebrating.

The Italian still has some ground to cover before he challenges Novak, Roger, and the rest for all-time hard-court dominance. But he has already upped the standard for the 2020s and posted one of the most remarkable two-year spans in the game’s history. Sinner has built an enormous gap between himself and the field, and it is increasingly difficult to see how his peers will close it.

* *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: