Every year, Challenger maven Damian Kust lists the players he thinks are likely to join the ATP top 100 in the coming year. He did a typically good job last year, picking 14 of the 20 players who reached the threshold in 2024. We can forgive him for missing Jacob Fearnley, who rose from 646th to the top 90 in less than twelve months.

I’ve yet to meet a forecast that I didn’t want to mathematically model, and this is no exception. An algorithm probably isn’t going to do better than Damian does, as it will miss all kinds of details accumulated by a full-time tour watcher. But the exercise will give us a better idea of what factors make it more or less likely that a player joins the top-100 club.

Let’s get straight to the forecast:

Rank Kust Player Rank Elo Rk Age p(100)

1 3 Joao Fonseca 145 45 18.4 96.5%

2 4 Learner Tien 122 74 19.1 92.4%

3 1 Hamad Medjedovic 114 91 21.5 89.1%

4 5 Nishesh Basavareddy 138 84 19.7 84.2%

5 9 Raphael Collignon 121 97 23.0 82.5%

6 8 Martin Landaluce 151 99 19.0 82.1%

7 6 Jerome Kym 134 111 21.9 79.6%

8 Leandro Riedi 135 108 22.9 71.9%

9 15 Jaime Faria 123 146 21.4 69.0%

10 7 Jesper de Jong 112 117 24.6 66.8%

11 12 Tristan Boyer 133 116 23.7 64.0%

12 2 Francesco Passaro 108 147 24.0 60.9%

13 Harold Mayot 116 154 22.9 57.6%

14 10 Alexander Blockx 203 102 19.7 56.8%

15 16 Valentin Vacherot 140 110 26.1 55.2%

16 11 N Moreno de Alboran 110 132 27.5 52.5%

17 Lukas Klein 136 126 26.8 47.0%

18 19 Elmer Moeller 160 160 21.5 37.4%

19 18 Duje Ajdukovic 142 171 23.9 36.6%

20 Terence Atmane 158 174 23.0 35.5%

21 R A Burruchaga 156 177 22.9 28.1%

22 Matteo Gigante 141 203 23.0 26.8%

23 13 Vit Kopriva 130 150 27.5 26.3%

24 Gustavo Heide 172 190 22.8 24.3%

25 Coleman Wong 170 238 20.6 24.3%

…

35 14 Mark Lajal 229 187 21.6 13.4%

…

41 17 Dino Prizmic 292 167 19.4 10.6%

42 20 James Trotter 193 175 25.4 10.4%

The table shows the 25 men who are most likely to make their top-100 debut this year, plus a few more from Damian’s list. I’ve included Damian’s rankings*, as well as each player’s year-end ATP ranking, year-end ranking on my Elo list, and their current age. The final column, “p(100),” is their probability of reaching the ranking milestone sometime in 2025.

* Damian points out that his numbering wasn’t intended as an explicit ranking, though he did end up picking the more obvious players first, with the long shots at the end.

The three columns between the players and their probabilities are the main components of the logistic-regression model. Age, unsurprisingly, is key. The younger the player, the more likely he’ll improve. Plus, the youngest men may have played limited schedules, causing their official rankings to underestimate their ability levels.

It’s a bit unusual to include both ATP rank and Elo rank, since they are simply different interpretations of the same underlying match results. In this case, though, it makes sense. Elo is better at predicting a player’s performance tomorrow, and it outperforms the official list as a way of predicting rankings a year from now. However, we’re trying to forecast ranking breakthroughs less than a year from now. If Fonseca has a good month Down Under, he’ll crack the top 100 in large part thanks to his eleven months’ worth of ranking points from 2024. In this model, then, the ATP ranking tells us how close a player is to the point total he needs. Elo tells us more about how likely he is pile up the remaining wins.

A player’s existing stock of points turns out to be somewhat more important than his underlying skill level. The model weights ATP ranking about half-again as heavily as Elo rank.

There are innumerable other variables we could include. I tested a lot of them. The only other input I kept was height. Height is only a minor influence on top-100 breakthroughs, but it’s definitely better to be taller. De Jong, for instance, is five feet, eleven inches tall. He ranks eighth on the 2025 list when height is omitted, and falls to tenth when height is included.

This tallies with the Challenger-to-tour conversion stats I worked out for my recent post about Learner Tien. Both short players and left-handers have a harder time making the jump than their taller, right-handed peers. Those conversions don’t address quite the same thing, since it’s possible to crack the top 100 with little to no success at tour level–it just means winning lots of Challengers. For that reason, left-handedness is probably an advantage for players aiming to jump from, say, 122nd to the top 100, as Tien is now. The relationship between left-handedness and breakthrough likelihood was less clear-cut than height, though, so I left it out.

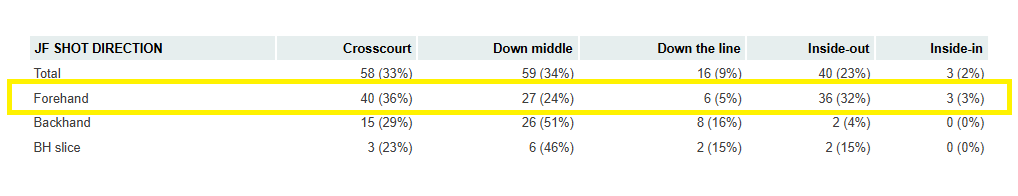

J-wow

Enough mechanics–back to the forecasts. Fonseca’s 96.5% probability might strike you as crazily high or outrageously conservative. It’s certainly confident, but then again the Brazilian is a special player. Barring injury–and immediate injury, at that–a breakthrough seems likely to happen soon.

Whether high or low, the Fonseca forecast is unusual. Like his forehand, it puts him in classy company. Going back to 2000, here are the players about whom the model would have been most optimistic:

Year Player Rank Elo Age p(100) Y+1 2021 Holger Rune 103 50 18.7 98.7% 10 2020 Sebastian Korda 118 48 20.5 97.9% 38 2024 Joao Fonseca 145 45 18.4 96.5% 2010 Grigor Dimitrov 106 75 19.6 96.3% 52 2020 Carlos Alcaraz 141 51 17.7 96.1% 32 2018 Felix Auger Aliassime 108 89 18.4 95.8% 17 2023 Hamad Medjedovic 113 66 20.5 95.4% 105 2000 Andy Roddick 156 52 18.3 94.5% 14 2020 Lorenzo Musetti 128 68 18.8 94.0% 57 2019 Emil Ruusuvuori 123 64 20.7 94.0% 84

It’s not so remarkable that eight of the nine other players on the list succeeded in reaching the top 100. The forecast would have expected (at least) that. But even including Medjedovic’s disappointing finish to 2024, the average ranking of these nine guys at the end of the following season (“Y+1”) is 45. Three broke into the top 20. And Fonseca’s forecast places him ahead of most of them.

Medjedovic’s near-miss was due in part to illness. It’s worth remembering that this model only predicts a single year; the young Serbian is still set up for a nice career. (Including, probably, a top-100 debut in 2025.) The model would have given Francisco Cerundolo a 90% chance of breaking through in 2021. He didn’t make it, yet he reached the top 20 a couple of years later. Fernando Gonzalez failed to convert an 80% chance in 2001, but after a few more years, he made the top ten.

Using a simple model–instead of the expert opinion of someone like Damian–exposes us to another type of error. The model is optimistic about the 2025 chances of 22-year-old Leandro Riedi, who possesses both official and Elo ranks on the cusp of the top 100. On paper, he’s a great pick. But he had knee surgery in September. Instead of defending points from two Challenger titles in January, he’s continuing to recover. He may ultimately surpass many of the other guys on the list, but even just regaining his pre-injury form this year is a big ask.

Waiting for Eva

Let’s run the same exercise for the women’s game. Unfortunately I don’t have enough height data, so we can’t use that. The resulting model is less predictive than the men’s forecast (even apart from the lack of player heights), but with year-end WTA rank, Elo rank, and age, it’s almost as good.

Patrick Ding took up the task of a Kust-style list for women. It’s unordered, so I’ve added a “Y” in the “PD” column next to his picks:

Rank PD Player Rank Elo Age p(100) 1 Y Eva Lys 131 43 23.0 80.1% 2 Y Anca Todoni 118 100 20.2 74.9% 3 Y Maya Joint 116 173 18.7 65.8% 4 Aoi Ito 126 109 20.6 65.4% 5 Y Marina Stakusic 125 131 20.1 62.3% 6 Y Polina Kudermetova 107 159 21.6 61.8% 7 Y Alina Korneeva 177 80 17.5 61.8% 8 Y Robin Montgomery 117 155 20.3 61.1% 9 Y Sara Bejlek 161 88 18.9 59.9% 10 M Sawangkaew 130 94 22.5 58.8% 11 Anastasia Zakharova 112 145 23.0 54.1% 12 Y Sijia Wei 134 135 21.1 49.9% 13 Y Celine Naef 153 124 19.5 48.8% 14 Y Antonia Ruzic 143 105 21.9 48.7% 15 Maja Chwalinska 128 119 23.2 47.7% 16 Y Sara Saito 150 182 18.2 43.1% 17 Alexandra Eala 148 162 19.6 41.6% 18 Y Darja Semenistaja 119 192 22.3 41.5% 19 Y Dominika Salkova 151 150 20.5 38.1% 20 Talia Gibson 140 185 20.5 37.2% 21 V Jimenez Kasintseva 156 170 19.4 36.3% 22 Y Ella Seidel 141 205 19.9 36.2% 23 Y Iva Jovic 189 157 17.1 33.8% 24 Daria Snigur 139 161 22.8 32.0% 25 Francesca Jones 152 106 24.3 31.5% 26 Y Solana Sierra 163 156 20.5 30.2% 27 Y Ena Shibahara 137 103 26.9 29.1% 28 Lois Boisson 204 95 21.6 23.9% 29 Elsa Jacquemot 159 191 21.7 21.8% 30 Y Taylah Preston 170 246 19.2 20.0% 31 Y Tereza Valentova 240 127 17.9 19.6% 32 Elena Pridankina 186 201 19.3 18.9% 33 Lola Radivojevic 185 186 20.0 18.9% 34 Y Oksana Selekhmeteva 176 176 22.0 16.8% 35 Barbora Palicova 180 202 20.8 16.2%

This isn’t quite a fair fight with Patrick, because he made his picks in early October. Two of his choices (Suzan Lamens and Zeynep Sonmez) have already cleared the top-100 hurdle. He would presumably consider Ito more carefully now, since she reached a tour-level semi-final two weeks after he made his list. I should also note that Patrick picked two prodigies outside the top 300: Renata Jamrichova and Mia Ristic. My model didn’t consider players ranked that low. I had to draw the line somewhere, and Fearnley aside, single-year ranking leaps of that magnitude are quite rare.

The mechanics of the algorithm are pretty much the same as the men’s version. The women’s list looks a bit more chaotic, pitting players with strong Elo positions (such as Lys and Korneeva) against others who are close to 100 without the results that Elo would like to see (Joint, Kudermetova, etc).

Eva Lys is fascinating because this is her third straight year near the top of the list. She finished 2022 ranked 127th, standing 71st on the Elo table. Just short of her 21st birthday, that was good for a 76% chance of reaching the top 100 the following year–second on the list to Diana Shnaider. She rose as high as 112, but no further.

A year older, Lys was fourth on the 2023 list. Her WTA ranking of 136 and her nearly-unchanged Elo position of 72 worked out to a 67% chance of a 2024 breakthrough. Only three players–Brenda Fruhvirtova, Erika Andreeva, and Sara Bejlek–scored higher. She came within one victory of the milestone in September but finds herself back on the list for 2024.

Even beyond Lys’s 80% chance of finally making it in 2025, history is encouraging. I went back 25 years for this study, and only two other players would have been given a 50% or better chance of reaching the top 100 for three consecutive years. Stephanie Dubois was on the cusp from 2005 to 2007, finishing the third year ranked 106th. She finally made it in 2008. More recently, Wang Xiyu was within range from 2019-21. (Covid-19 cancellations and travel challenges didn’t help.) She not only cleared the hurdle in 2022, she did it with style, climbing to #50 by the end of that season.

The same precedents bode well for Bejlek, who had a 52% chance of breaking through in 2023, a 77% chance last year, and a 60% probability for 2025.

Mark your calendars

In twelve months, we can check back and see how the model fared against Damian and Patrick. The algorithm has the benefit of precision, and it is less likely to get overexcited about as-yet-unfulfilled potential. The flip side is that it doesn’t consider the innumerable quirks that might bear on the chances of a particular player.

For now, I’m betting on the humans.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: