I run a lot of queries, and people often ask me arcane trivia questions. Has this ever happened before? Is that a record? My beat seems to be the super-niche stuff that no one would ever bother to include in the official media notes.

The Trivia Notebook is my attempt to put more of the answers in one place. I’m thinking I’ll do one of these every two or three weeks. If you have a question or topic you think would fit well here, please send it. No promises–most of my ideas don’t end up making the cut.

It’s a new year, so we’re all bursting with energy to start new projects. Most of them are long gone by April, and odds are the same thing will happen to this one. But hey, you never know, right?

In this first installment, we’ll look at 100-point ranking leaps, marathon man Tomas Martin Etcheverry, seedless quarter-final lineups, and single-country duos that conquered a tournament.

100-spot ranking leaps

Joao Fonseca ended 2024 ranked 145th in the world. My Elo ratings put him 45th, and after the Canberra title last week, his place on that list climbed to 27th.

As with many trivia questions, we’ll need to be a bit more specific. Tons of players move up 100 places each year, but going from 845th to 745th–while impressive!–is presumably not the sort of thing we’re looking for. Same thing with injury recoveries. While Pablo Carreno Busta finished 2024 ranked 196th, it won’t be momentous if the former top-tenner bounces back to the top 100.

A narrower question, then: Which players have jumped at least 100 ranking places in a single year, ending with their first year-end top-100 finish?

Here are the biggest single-year improvements that ended with a top-100 debut:

Player Year Prev YE New YE Jump Kenneth Carlsen 1992 835 69 766 Leonardo Lavalle 1985 745 87 658 Guillermo Coria 2000 722 88 634 Pablo Carreno Busta 2013 654 64 590 Marco Chiudinelli 2009 605 56 549 Jacob Fearnley 2024 645 99 546 Josef Cihak 1987 613 77 536 Andreas Vinciguerra 1999 633 98 535 Andre Agassi 1986 618 91 527 Alex Michelsen 2023 599 97 502 Arnaud Di Pasquale 1998 572 81 491 Radek Stepanek 2002 542 63 479 Ben Shelton 2022 573 96 477 Fritz Buehning 1979 555 81 474 Jannik Sinner 2019 551 78 473

Pablo made it! A few other names there you might recognize, too.

If Fonseca skips forward 100 spots, he’ll do something that sets him apart from everyone on that list: He’ll leap into the top 50. Still, a 100-spot move is hardly historic:

Player Year Prev YE New YE Jump Marc Rosset 1989 474 45 429 Ronald Agenor 1985 418 49 369 Goran Ivanisevic 1989 371 40 331 Vincent Van Patten 1979 374 43 331 Sergi Bruguera 1989 333 26 307 Juan Carlos Ferrero 1999 346 42 304 Jim Courier 1988 346 43 303 Horst Skoff 1986 299 42 257 John McEnroe 1977 264 18 246 Ulf Stenlund 1986 274 34 240 Mark Philippoussis 1995 274 38 236 Peter Lundgren 1985 265 31 234 Ricardo Cano 1975 274 42 232 Jack Draper 2022 265 42 223 Mel Purcell 1980 245 27 218

About 80 players have made a 100-plus-spot jump into the top 50. It’s harder to do so now than it was in the days of McEnroe or Courier, but men still manage it with some regularity. Fonseca will have to settle for breaking other records.

Marathon men

This was the Adelaide second round. Thanasi Kokkinakis decided this was enough for his Australian Open prep, as he withdrew from the quarters. Headlines about this match tended to focus on Thanasi’s penchant for marathons. He’s well-known for his 5h45 battle with Andy Murray two years ago in Melbourne. Last year, he went 3h15 against Aleksandar Kovacevic in Houston, then 3h29 a week later at the Sarasota Challenger against Gabriel Diallo.

But… the name that caught my eye was Tomas Martin Etcheverry. While he doesn’t have a marquee marathon to his name like the Murray tilt, he spends a lot of time on court. Just three months ago, he muscled through three hours and 43 minutes to beat Botic van de Zandschulp in Shanghai.

Etcheverry doesn’t have a ton of slam experience, and the best-of-five format lends itself to memorable marathons. But in best-of-three matches, the Argentinian has now crossed the three-hour mark more than any other active player:

Rank Player Bo3 Marathons 1 Tomas Martin Etcheverry 27 2 Albert Ramos 26 3 Novak Djokovic 25 4 Pedro Martinez 24 5 Carlos Taberner 23 6 Thiago Monteiro 22 7 Roberto Carballes Baena 20 8 Mikhail Kukushkin 19 8 Timofey Skatov 19 8 Juan Pablo Varillas 19 8 Thanasi Kokkinakis 19 12 Lorenzo Giustino 17 13 Jordan Thompson 16 13 Alessandro Giannessi 16 13 Marton Fucsovics 16

This is an imprecise measure, because it’s really “three-hour matches I know about.” It includes tour-level matches back to 1991, tour qualies and Challengers going back a decade, and Challenger qualies for the last few years. So it’s biased a bit toward younger players, who have played more in the “Jeff knows about their match times” era. Still, it’s an impressive tally for Etcheverry–and he’s only 25 years old.

The Kokkinakis match also tied Etcheverry for first place on the all-time list with Nicolas Massu. Here’s that leaderboard, again with the caveat that older players do not have Challenger matches counted:

Rank Player Bo3 Marathons 1 Tomas Martin Etcheverry 27 1 Nicolas Massu 27 3 Albert Ramos 26 3 Carlos Berlocq 26 5 Novak Djokovic 25 5 Rafael Nadal 25 5 Andy Murray 25 8 Pedro Martinez 24 9 Carlos Taberner 23 10 Thiago Monteiro 22 10 Paolo Lorenzi 22 12 Adrian Menendez Maceiras 21 13 Roberto Carballes Baena 20 14 Mikhail Kukushkin 19 14 Timofey Skatov 19 14 Juan Pablo Varillas 19 14 Thanasi Kokkinakis 19 18 Gilles Simon 18

Legends one and all. It’s continually amusing to me that Djokovic, Murray, and Nadal have landed on the same number. Roger Federer, for his part, only reached three hours in six of his short-form matches.

Seedless quarter-finals

At the Nonthaburi Challenger this week in Thailand, the quarter-finals featured a wild card, two qualifiers, and an alternate… but no seeds. One of the seeds withdrew, five lost in the first round, and the remaining two fell in the second.

Let’s say it together: Has that ever happened before?

In fact, there were seedless quarter-finals five times at Challenger level last year, including once in Nonthaburi! Altogether, there have been more than 80 such tournaments in Challenger history. Even “two seeds in the second round” isn’t that special–it happened at Amersfoort last year.

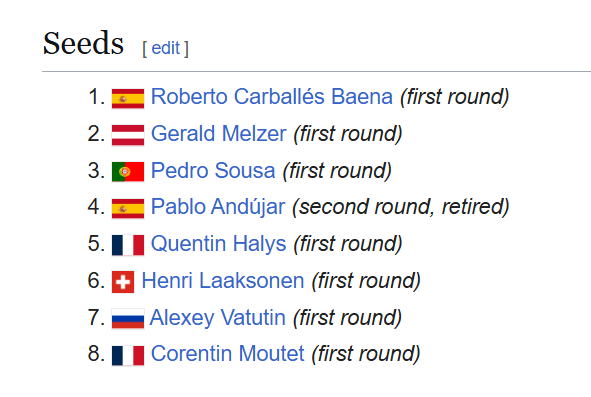

What about one seed in the second round? For that, we have to go back to 2018 in Lyon, where a 17-year-old Felix Auger-Aliassime defended his title. Gotta love the Wikipedia summary of how things went for the seeds:

As far as I can tell, that’s the closest we’ve come to a Challenger with no seeds in the second round. Credit to Pablo Andujar, he did his best.

Lonely countrymen

Last one, this time from the archives. Last year at the Dobrich Challenger, two Dutchmen–Jelle Sels and Guy den Ouden–met in the final. It isn’t unusual to have players from the same country in a Challenger final, even outside their home country. What was odd about Dobrich is that Sels and den Ouden were the only Dutch men in the main draw.

You know the drill: Has that ever happened before?

I should know by now: Ask that question about the varied history of the Challenger tour, and the answer is almost always yes. It happened again in September, when two Japanese men met for the Columbus final. It also arose twice in 2023. Two Bosnians played for the championship in Sibiu, and the San Benedetto title match was contested between Benoit Paire and Richard Gasquet, the only Frenchmen in the draw.

Altogether, there have been 32 such Challengers. There were none in the first decade of the tour, but they’ve clicked off about once per year since. My favorite of the bunch is the 1998 Fürth Challenger, where Christian Ruud and Jan Frode Andersen saw off all of their non-Norwegian foes.

This scenario has also come up about as often at tour level. More than half of them were before 1980, and they’ve gotten progressively rarer. But we got one in 2024! Arthur Fils and Ugo Humbert were the only two Frenchmen in the Tokyo draw, and they were the last two men standing. That was the first such tournament in a decade, since Monte Carlo in 2014, where Stan Wawrinka upset Roger Federer for the title.

That, I think, is enough tennis trivia for one day. We’ll have some more–maybe!–in a couple weeks.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: