Here’s a stat to get us rolling: In yesterday’s fourth round match at the the Australian Open, Elina Svitolina won 67% of points when she hit a backhand. Tour average is a neutral-as-its-gets 50%. Svitolina, with her resourcefulness off that wing, averages 51%.

It gets even better. Usually, if a rally statistic comes out much above 50%, it’s because it’s loaded with winners. But against Veronika Kudermetova yesterday, Svitolina hit just one backhand groundstroke winner. She induced two more forced errors, but committed five unforced errors of her own. All of which is to say, those point-winning backhands came thanks to point construction, not swinging for the fences. (An erratic Kudermetova helped, too.)

The backhand masterclass, on the heels of another strong baseline performance against Jasmine Paolini in the third round, recalls Svitolina’s peak. The Ukrainian is now 30 years old, veteran of innumerable injuries, a pregnancy, and the perpetual distraction of her country at war. My Elo ratings suggest that she was at her best nearly seven years ago, after she upset Simona Halep for the the 2018 Rome crown. That’s an eon in tennis time: She hasn’t held a place in the top ten since 2021.

Yet here she is, in the Melbourne final eight. It’s her twelfth major quarter-final, her fourth since becoming a mother. She might have made it one more a year ago. After a grueling runner-up finish in Auckland to open her 2024 campaign, Svitolina raced through three rounds at the Australian before retiring to Linda Noskova in the fourth round. This year, she skipped the warmups and has sustained her best tennis on the bigger stage. With Madison Keys across the net tomorrow, she has a chance to go even further.

Svitolina 2.0 will probably never reach the level she showed in the mid-2010s. She’s a half-step slower, and she needs to manage her schedule with care. But like all players with successful second chapters, she has changed her game in response to her limitations. She is, and always will be, a counterpuncher, leaning on one of the game’s sturdiest backhands. Yet the new Elina has first-strike weapons that her younger self could only dream of.

Hitting big

While no one is about to mistake her for Aryna Sabalenka at the service line, the 30-year-old does more damage than she used to.

Yesterday against Kudermetova, Svitolina averaged almost 103 miles per hour (165 kph) on her first serves. I have first-serve speed for more than 70 of her career slam matches, and she hit that level in only five of them, mostly at Wimbledon. When she reached the quarters at the 2021 US Open, she averaged less than 100 miles per hour in all five matches.

It’s a small improvement, but coupled with increased precision on the first serve, it is paying off. In the sample of Match Charting Project-logged matches, she converted more plus-ones behind her first serve in 2024 than her career rates. Even her improved 2024 marks pale in comparison to what she has done in Melbourne:

Span Unret% <=3 W% Career 27.2% 38.6% 2024 27.5% 41.9% R3 vs Paolini 36.1% 60.6% R4 vs Kudermetova 39.4% 63.9%

The second column, showing the percent of first-serve points in which Svitolina won the point with her serve or second shot, is where players make their money. No matter how good your ground game, it's tough to make up a deficit in the cheap-points category. Through 2024, the Ukrainian was middle-of-the-pack in both of the stats. The form she has shown in the last few days is something entirely different.

The numbers are particularly impressive against a defender like Paolini. While the Italian probably isn't as strong as her #4 ranking suggests, she is certainly an elite returner. In charted matches last year, she put nearly three-quarters of first serves back in play. Svitolina allowed her only 64%. And as we see with the serve-or-second-shot stat, Paolini couldn't do much when she did get the ball back. On average, the Italian wins more than half of the first-serve points in which she lands her return. On Friday, she won just 6 of 23.

There's just one reservation about the third-round performance. Svitolina got those results by taking chances, and she made fewer than half of her first serves. It was a day of extremes: 48% of first serves in, 83% of first-serve points won, and 42% of second-serve points won. Had she explicitly targeted a more typical 60% rate of first serves in, she wouldn't have posted the same win rates. But with a first-class returner across the net, Svitolina's tactics were proven correct.

That half step

So far we've talked about what the Ukrainian can control. Just as important is what she can't: The aging process and its effect on the rest of her game.

Here's an overview of how her current level compares to her 2017-20 peak, measured by first-serve and second-serve win percentages, along with return points won:

Span 1st W% 2nd W% RPW% 2017-20 66.6% 47.2% 46.1% 2023-25 65.5% 46.8% 45.2%

Approximately a one-percentage-point drop across the board. That makes sense as an explanation of the difference between a player ranked around #5 and one who should be hovering around #20. (Elo is more optimistic than Elina's official ranking of #27.)

Now try the same stats, hard courts only:

Span 1st W% 2nd W% RPW% 2017-20 67.5% 47.3% 46.1% 2023-25 68.9% 47.9% 43.6%

At her peak, Svitolina was basically the same player on all surfaces. Now, she sports a different type of surface profile. The service aggression is paying off, while she seems to be struggling to do return damage on faster courts.

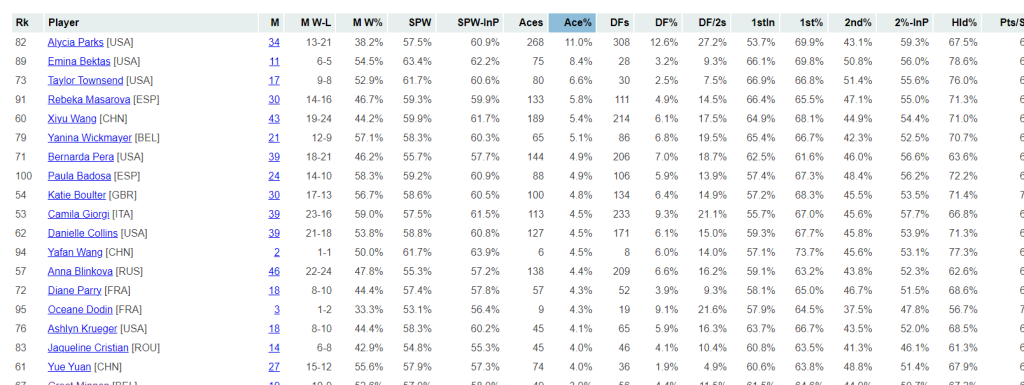

The 30-year-old has always aimed to get a lot of serves back. According to MCP data, she has put 77.5% of serves in play, a number that fell to 76.4% last season. Both marks are near the top of the table. Players who adopt such a defensive posture usually don't win a particularly high rate of those points, and Svitolina is no exception: Her 51.5% win rate when she puts the return in play is roughly tour average. It's a low-risk, fairly-low-reward strategy.

Against strong servers, the results can be bleak. She got fewer than 65% of serves back against Sabalenka in Cincinnati last summer, and even Ons Jabeur held her to 67% at Wimbledon. In Adelaide three years ago, Madison Keys was so strong from the line that Svitolina put only half of returns in play. At her peak, it was rare for the Ukrainian to fall below 70%.

Her hard-court results, then, depend a great deal on the matchup. The relatively punchless Paolini was a lucky draw in this regard. Once the serve and the plus-one are past, Svitolina can go toe-to-toe with anybody. She won 60% of points that lasted four or more strokes against the Italian. Facing Kudermetova, as we've seen, it was even easier. Once Elina got her racket on a backhand, the Russian basically gave up.

It's a mad, mad quarter-final

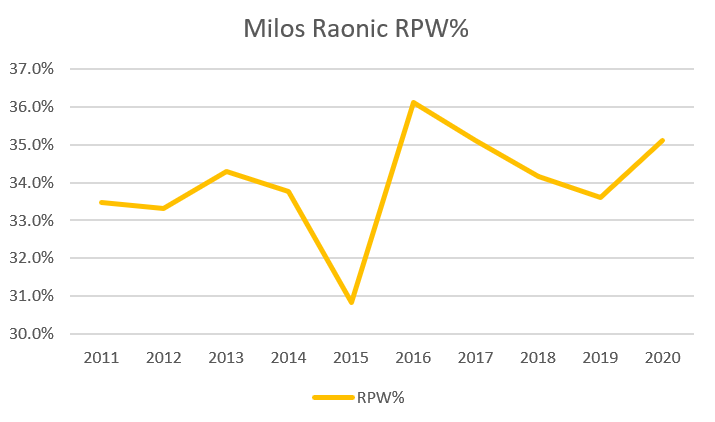

Svitolina's next challenge is entirely different. In five career meetings, she has two victories against Keys, coming at the Australian Open and US Open in 2019. Even when she was younger, she couldn't neutralize the American's serve. She has won about 36.5% of return points in their head-to-head, never topping 43.3% in a single match.

The margins for the Ukrainian tomorrow will be slim. While Svitolina has boosted her serve, she has gained more plus-one points than unreturned serves. That works against opponents like Paolini, but Keys swings big at everything, including hard serves. In the Adelaide final against Jessica Pegula--a broadly similar player to Svitolina--Keys held her opponent's serve points to an average of 3.1 strokes. That's a lot of short "rallies," and it means fewer chances for Elina to put away a weak second ball.

Svitolina will find herself even more powerless on return. As we've seen, Keys is responsible for one of the worst performances of her career. In that 2022 Adelaide match, the 30-year-old won a miserable 22% of return points. The longer the rally, the better for Svitolina. But Keys will try to prevent the commentators from using the word "rally" at all. In the Adelaide title match, the American's service points lasted, on average, a mere 2.6 strokes.

The Ukrainian may not have much control over the proceedings, but that isn't to say she doesn't have a chance. My forecast leaves her plenty of room, giving her a 42.5% shot at reaching the final four. Keys's aggression often goes astray, and nagging injuries could hamper either player. If the American can't serve at 100%, or if she falls back on more passive tactics, the underdog will pounce. In longer points, Svitolina is the clear favorite. She'll have to hope she gets the chance to play some.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: