Also today: January 18, 1924

It’s been a wild 2024 so far for Jiri Lehecka. He took a set from Novak Djokovic at the United Cup, beat Jack Draper for his first career ATP title in Adelaide, and then, defending quarter-finalist points at the Australian Open, lost today in the second round to 91st-ranked Alex Michelsen.

Even before the roller-coaster January, it was clear that the Czech was someone to watch. Ranked 23rd on the ATP computer, he’s the fifth-best player on tour under 23. He scored two top-ten victories last year–over Andrey Rublev and Felix Auger-Aliassime–and outlasted Tommy Paul in a gripping third-round five-setter at Wimbledon. For a moment it seemed that Czech men’s tennis had fallen into an uncharacteristic lull; with Lehecka, Tomas Machac, and 18-year-old Jakub Mensik on the rise, the country’s fortunes are headed back in the right direction.

Lehecka’s signature skill is raw power. A feature on the ATP website last February highlighted his average forehand speed of 79.2 miles per hour, a rate that compares to the likes of Rublev, Auger-Aliassime, and Jannik Sinner. He’s so strong that he propels those rockets without even looking like he’s trying. Rublev signals that a big swing is coming with an emphatic grunt; upon ignition, Lehecka demeanor is barely distinguishable from the pre-match warmup.

Yet the eye-popping power hasn’t shown up on the statsheet. According to my forehand potency metric, FHP, Lehecka ranks near the bottom of ATP regulars. His FHP is only 1.4 per match, right behind Diego Schwartzman. Rublev’s FHP per match is ten times higher, at 14.7. Same shot–at least according to the radar gun–but very different results. Converting FHP to points won, Rublev’s forehand earns eight or nine points each match that Lehecka’s forehand does not.

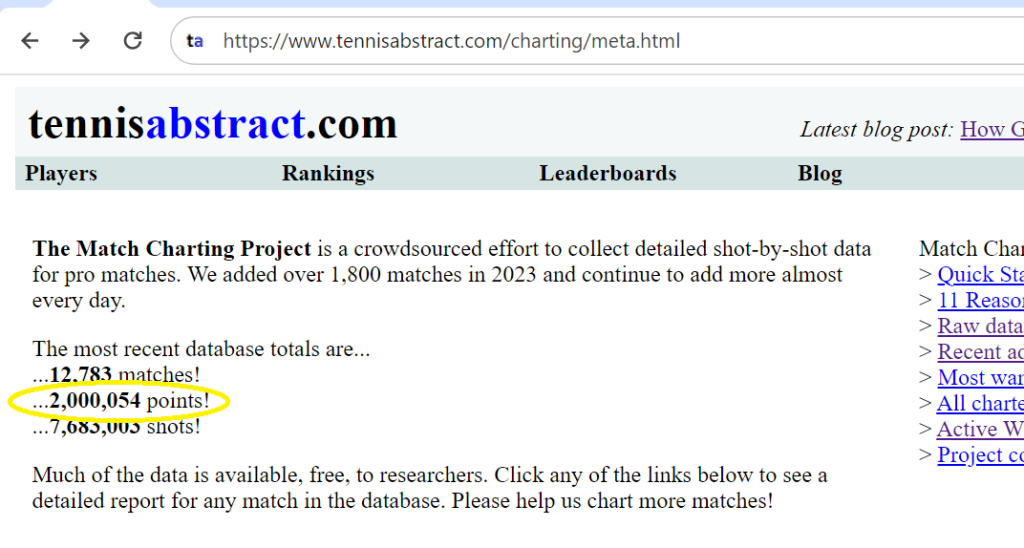

The Czech’s groundstroke winners are some of the prettiest on tour: compact strokes resulting in lasers that opponents can only watch from afar. He can turn on a second serve as well as anyone. But more often, he plays like someone without those natural gifts. One of his favorite shots is the groundstroke from the middle of his court back up the middle, deep. That choice is never a liability, exactly: opponents can rarely respond with an aggressive shot of their own, due in part to Lehecka’s natural power. But it never generates winners, and it doesn’t appear to have positive follow-on effects, either. According to Match Charting Project data, after hitting a down-the-middle forehand, he wins points 47% of the time, roughly in line with tour average.

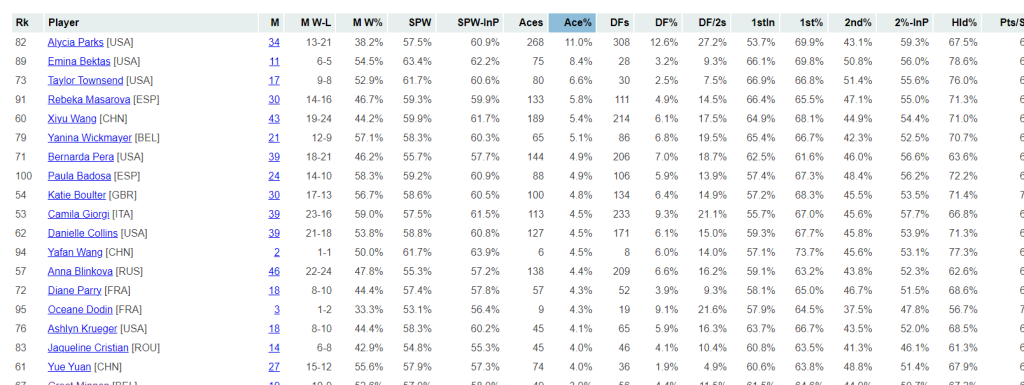

It isn’t just the forehand. Few ATPers hit so many balls down the middle. The following table shows most of the players ahead of him in the rankings, along with the rates at which they hit groundstrokes in general down the middle (All DTM), and how often they hit forehands down the middle (FH DTM):

Player All DTM FH DTM Alex de Minaur 35.8% 28.8% Jiri Lehecka 34.2% 27.9% Holger Rune 33.0% 26.9% Jannik Sinner 29.7% 25.7% Alexander Zverev 29.4% 28.8% Ugo Humbert 29.3% 27.2% Cameron Norrie 29.2% 22.8% Taylor Fritz 28.7% 26.8% Grigor Dimitrov 28.3% 20.5% Nicolas Jarry 27.8% 22.5% Player All DTM FH DTM Daniil Medvedev 27.5% 27.8% Karen Khachanov 27.0% 22.0% Adrian Mannarino 26.8% 25.0% Frances Tiafoe 26.7% 21.9% Stefanos Tsitsipas 26.4% 22.3% Novak Djokovic 26.0% 21.1% Carlos Alcaraz 26.0% 22.6% Tommy Paul 25.8% 20.3% Casper Ruud 25.5% 21.1% Andrey Rublev 24.3% 18.1% Hubert Hurkacz 21.0% 16.6%

Only de Minaur goes up the middle more often, and he is a very different kind of player. While fellow basher Sinner is near the top of the list, even he is five percentage points less likely than Lehecka to take the conservative route. Rublev earns his baseline success by going to the other extreme. The forehand-specific numbers tell a similar story, except that Zverev and Medvedev join Lehecka and de Minaur near the top.

In theory, a crush-it-deep-down-the-middle strategy could work, but there’s little evidence that it does. The typical tour player wins 46% of the points when they hit a forehand down the middle, versus 56% when they hit a forehand elsewhere. True, the direction of every shot isn’t entirely in their control: some of those down-the-middle forehands are recovery shots. But many more are in the hands of the player who hits them. Lehecka’s power should generate, on average, weaker replies, meaning that his flexibility to choose his next shot is greater than that of his peers.

Against Draper in the Adelaide final, the Czech took a few more chances. Only 30% of his groundstrokes went down the middle, and an awful lot of those were very deep. He won 54%–an unusually high rate–of points in which he hit a forehand or backhand down the middle. He also didn’t miss, committing just one unforced error in that direction for the entire match. Lehecka, similar to the tour as a whole, usually hits unforced errors on about one-tenth of their shots down the middle.

Those numbers sound unsustainable, and today’s match against Michelsen suggests that they were. The young American kept the pressure up, and Lehecka responded by reverting to form. 42% of his groundstrokes went down the middle, he missed one in ten of them, and all told, he won just 45% of those points. Trade in those numbers for his results from the Adelaide final, and the Michelsen match becomes a dead heat.

The Czech, in short, seems to be squandering his raw power. His ace rate is slightly below tour average, his first-serve win percentage even more so. There’s no guarantee that directing more groundstrokes–especially forehands–to the corners would be a net improvement, but the Rublev’s example indicates that there are immense potential gains in that direction.

It isn’t easy to achieve the proper balance between point-winning aggression and not-point-losing passivity. Lehecka has many more years to figure it out. Until he does, we can continue to marvel at the blistering forehands of a player outside the top 20.

* * *

January 18, 1924: In or Out?

One hundred years ago this week, the governing bodies of tennis were busy determining who wasn’t allowed to compete.

Regional associations in the United States were mulling a proposed USLTA rule that would revoke the amateur status of players who earned money writing about the sport. This was much more than a formality: Bill Tilden and Vinnie Richards, two of the strongest men in the game, were among those who earned their livings as journalists. Tennis was only slowly adapting to marquee names who didn’t come from money: Richards had once been suspended for working too closely with a sporting goods company, and Tilden rarely saw eye-to-eye with the men who ruled the federation.

On January 15th, the California LTA endorsed the regulation. The West Coasters tended to be a little less stodgy than the more tradition-oriented East Coast bodies, so the announcement did not bode well for Tilden’s and Richards’s chances of continuing in the amateur ranks. Tilden was ready to call the bluff: The 1925 squad for the all-important Davis Cup would look awfully fragile if the moonlighting journalists weren’t on it.

Another, more concrete decision, came down on the 18th. Molla Mallory, the Norwegian-born American star and seven-time US champion, was ruled ineligible for the Paris Olympics that summer. Tennis was still part of the Games, though 1924 would be its last appearance for decades. The USLTA had asked the International Olympic Committee for clarification: Would Mallory, would had represented Norway in 1912, be able to suit up for her adopted country?

The answer that arrived was negative–and it was worse than that. She couldn’t play for the US, because of her earlier appearances for Norway. But since she was now an American citizen, due to her 1919 marriage to businessman Franklin Mallory, she couldn’t play for Norway either!

The second flap was soon forgotten. Two weeks later, a clarification came from the IOC that Mallory was eligible to represent Norway, as she had been born there. She competed for her native country, losing in the quarter-finals to 18-year-old American sensation Helen Wills. Her chances in the doubles didn’t amount to much, since the rest of the Norwegian team was unknown abroad. With Jack Nielsen, she won a round in the mixed before falling in straight sets to the eventual silver medalists, Richards and Marion Zinderstein.

Richards had to suspend his journalistic activities to compete in Paris, since the IOC already had a policy preventing athletes from getting paid for writing about the Games. He didn’t regret it, winning gold medals in both singles and doubles. Tilden, though, honored his writing contracts and skipped the event. Besides, he said, Davis Cup was more important. He’d rather save energy for that.

Tilden would win the staredown with the USLTA, and famous tennis names would feature as newspaper bylines for years to come. Within a decade, full-time newspapermen would joke that their jobs were in danger from all the competition. In reality, those same anonymous journalists were writing the words that went under the better-known bylines. Only a few star athletes, including Tilden, cranked out their own copy.

Ghostwriting, then, was one of the early ways for “amateur” standouts to cash in on their celebrity. And in part, it was the reason that 1924 was the sport’s last full appearance at the Olympics for six decades. The IOC feared that tennis, for all its pretense to the contrary, had become too professional. As such, it didn’t belong in the Games.

Decades later, players would seize control of their own fates, even earning the right to compete in the Olympics as professionals. By then, the issues pitting athletes against federations would be different, but the movement could trace its roots to Bill Tilden and his insistence that he be allowed to write about tennis for money.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: