Previous: March

Lots of tennis this month, and I have an even-more-mixed bag than usual for you:

1. The Match Charting Project hit a fun milestone a few days ago, as we added our 2,000th unique player, Hanna Chang. She was quickly followed by 1989 Australian Open semi-finalist Jan Gunnarsson. We’re also just a few charts away from 7,000 women’s matches.

2. Stat of the month has go to Jenson Brooksby, who saved match point in three separate matches en route to the Houston title. Voo de Mar has some context: It was the first time for such a feat in nearly 25 years:

Runner-up stat of the month might be that Patrick Maloney–ranked 390th when he lost to Brooksby in Houston qualifying–came back a week later and knocked Brooksby out of the first round of the Tallahassee Challenger. As Mike Cation put it: Tennis, man.

3. Hollywood agent Ari Emanuel, with partners, is buying the Miami and Madrid tournaments from IMG as part of a $1 billion deal.

I generally don’t care much about who owns which tournaments, but in this case, there could be impact on the tennis itself. Not necessarily positive or negative: IMG likes to give wild cards to its own up-and-coming clients. 16-year-old Moises Kouame was one beneficiary this week, for instance. New owners might favor youngsters, too, but presumably not IMG clients in particular.

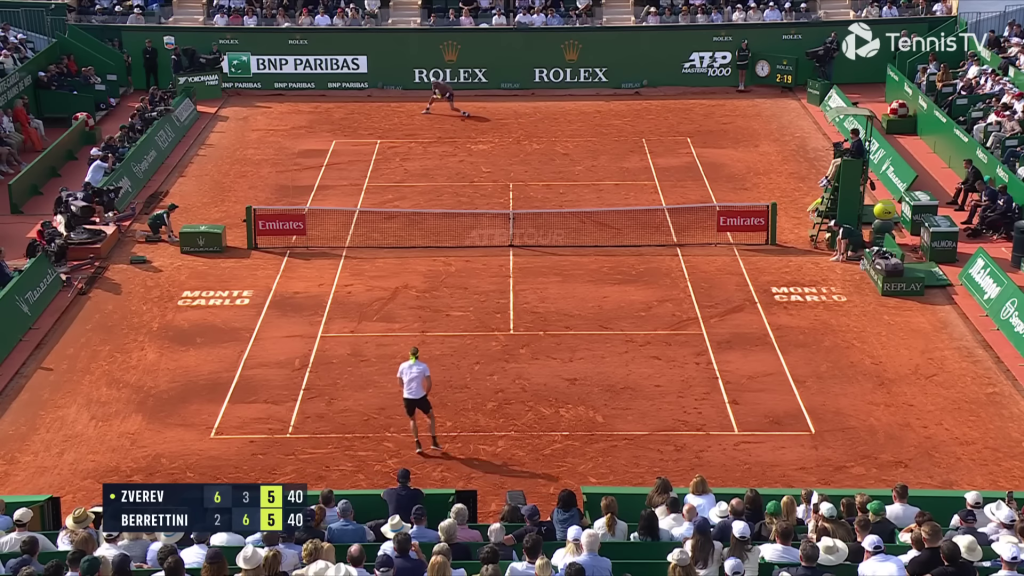

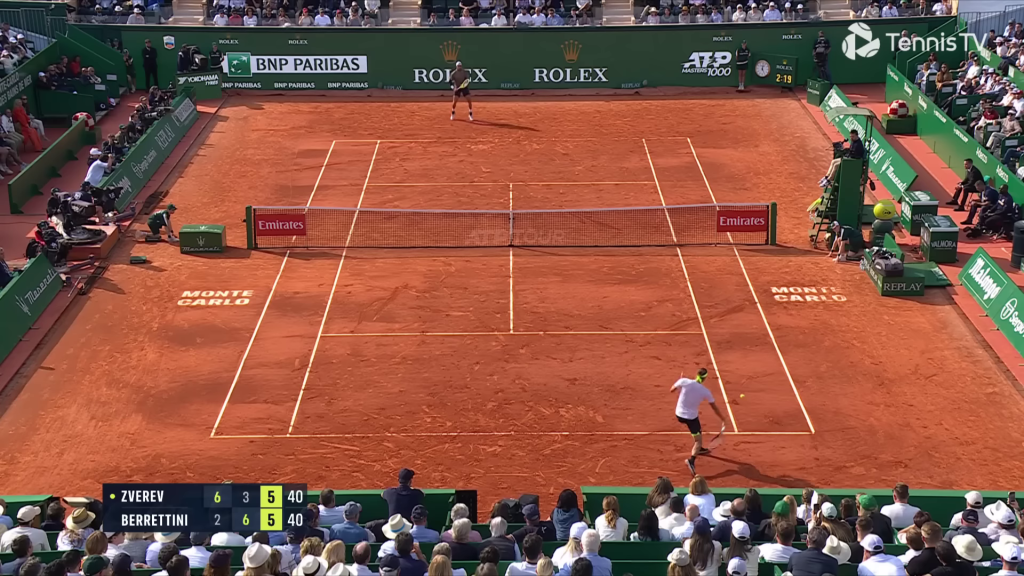

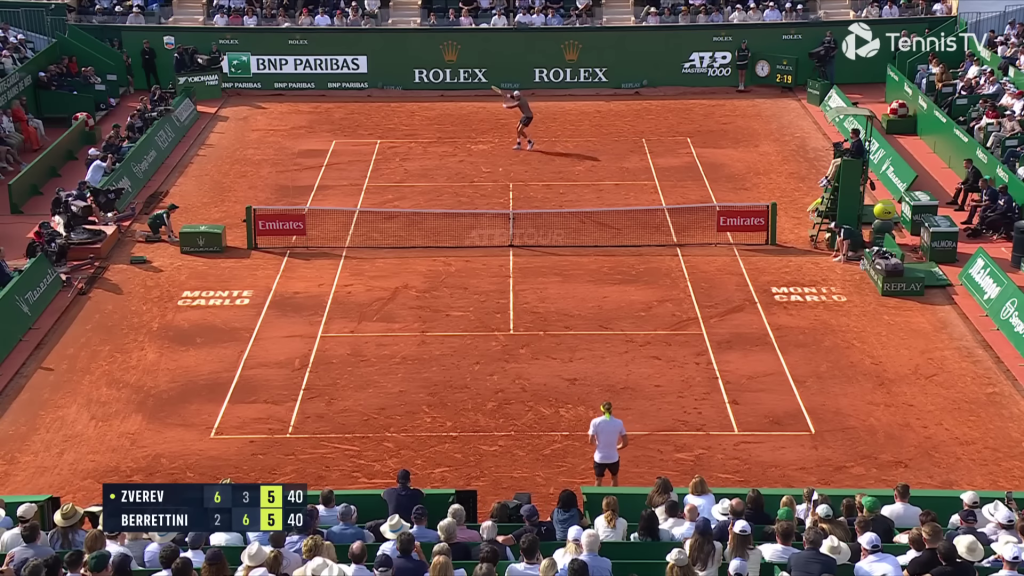

4. Hugh recaps the Barcelona final:

If we cast our eyes back to the first break point of the match that Alcaraz won, we’ll note that he had to do just that: win it. In other words, Rune wasn’t giving anything in this match. He played the role of counterpuncher perfectly from a deeper court position, yet never abandoned his forecourt instincts when the opportunity arose. Perhaps the rashest shot he hit all day was the forehand return he threaded on set point.

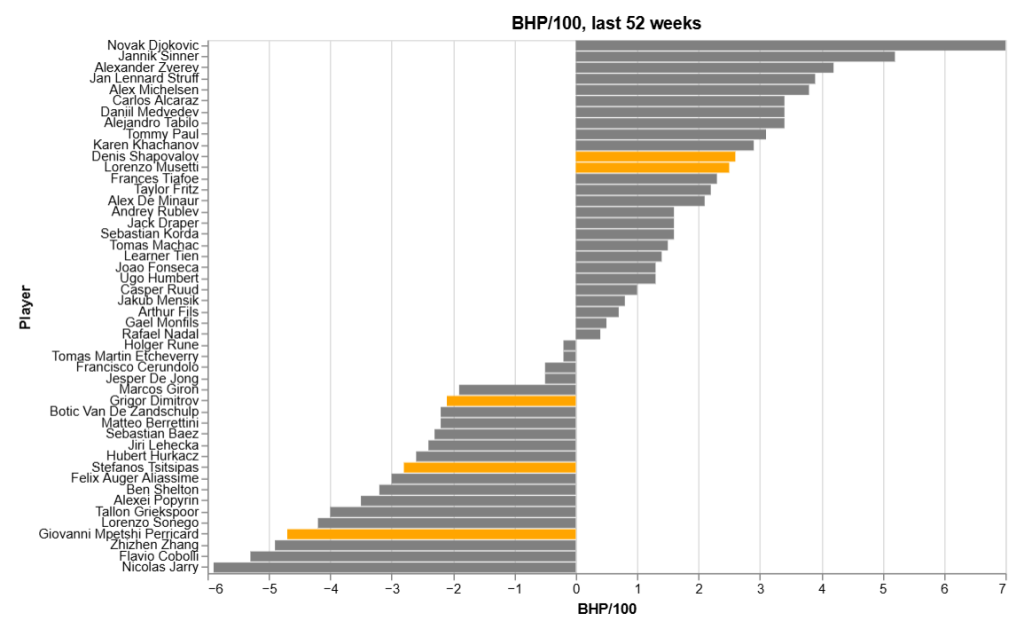

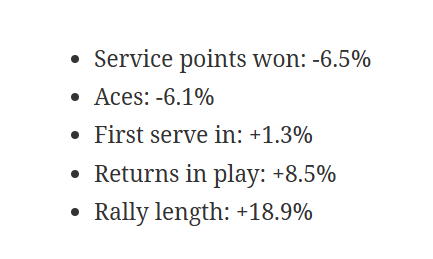

5. Speaking of Barcelona, did you know it now plays slower than Monte Carlo? I did not. Here are my surface speed ratings from the last 52 weeks:

(A few tournaments are included twice because their 2024 editions fell less than 365 days before the current one.)

For many years, Monte Carlo was the most extreme of any event above the 250 level. By my metric, at least, it has now swapped places with Barcelona, which suddenly got slower in 2023. It was never fast, by any means, but 2023-25 is a new era for conditions at the event.

6. The college tennis season is hotting up, which means it’s time to point you to CollegeTennisRanks. Chris does an impressive job, from upcoming schedules to his mind-bogglingly complex What-If scenarios.

7. Archive video of the month is courtesy of the USTA, with a 1989 US Open second-rounder between Jimmy Connors and Bryan Shelton:

If that isn’t enough, there’s also video–thanks again to Voo–of a 1994 final featuring ATP bigwig Andrea Gaudenzi.

8. Was Ethel Mildred Brooksmith (1865-1944) the early lawn tennis player known as Miss M. Brooksmith? It seems likely.

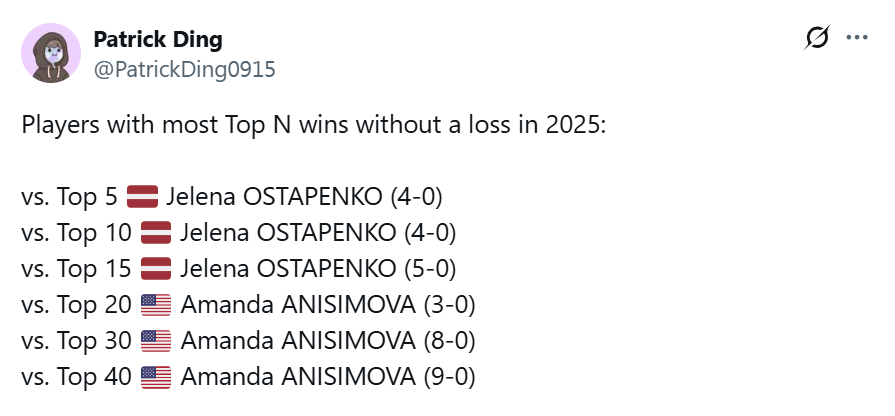

9. A few days ago I wrote about the Ostapenko-Swiatek head-to-head. Our new task is to analyze the Ostapenko-Azarenka matchup (5-0 in favor of Vika) for clues, just as Wim Fissette and many other coaches are probably doing.

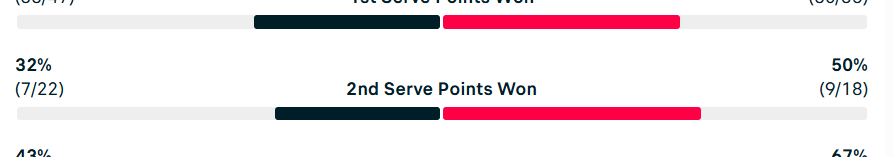

If the Vika method doesn’t work, what’s Iga’s next move? Many of you suggested that she needed more variety. Sure, I guess, it doesn’t hurt. But that misses the point. The average rally length in these matches is usually below three shots–there’s no time for variety! If you win all the long rallies, congrats, you’ve won what, six points? The match is decided on serve, serve returns, and some plus-ones. The best you can do is nudge Ostapenko away from cleaning up in those categories.

Hyper-aggressive game styles are endlessly fascinating to me, in part because they end up influencing everything else. Against Swiatek in Stuttgart, the average rally length was 2.7 shots. Against Sabalenka in the final, it was 2.6. Basically the same, against two such different players! Sabalenka arguably played better defense, even though her scoreline was more lopsided.

And then, after all this, Ostapenko went to Madrid and lost her first match to the unranked (not unseeded, unranked) Anastasija Sevastova. She’ll have to wreak more havoc another time.

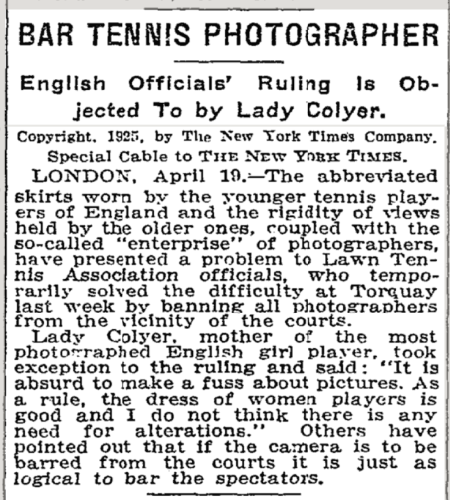

10. One hundred years ago this month, the British LTA banned photographers:

The header photo above, of Evelyn Colyer and Joan Austin, shows just how scandalous the dress of the day could be.

11. Also in April 1925–a century ago today, in fact!–Bill Tilden was a very busy man. He won the singles final at the Greenbrier Country Club in West Virginia, then lost the doubles. In the third set of the mixed final, rain wiped out the remainder, and the match was called a draw.

As if that wasn’t enough, Tilden began a 500-mile journey to Rye, New York, for an exhibition match the next day.

Best part of it all is that both venues–the Greenbrier and the Biltmore (now Westchester) Country Club–are still around.

12. Matt Futterman has a great profile on rising American Ethan Quinn:

“I thought I was going to come on tour and explode, like Ben Shelton did, or Alex Michelsen,” Quinn, a 21-year-old native of Fresno, Calif. with wavy blond hair and a boyish visage, said during a March interview in Indian Wells. “I thought I was going to take it by storm. That didn’t happen.”

Nearly two years on from Quinn’s decision, he has evolved into a better tennis player but also into a fable whose ultimate lesson remains unknown.

Futterman came on my podcast a few years ago. He asked me then what kind of coverage I’d like to see more of in the Times. I’m not sure I gave him a good answer. Now I have a better one: More of this, please!

12. In the Munich event’s first year as an ATP 500, the field seemed cursed. Several players withdrew the previous week, and five more pulled out after the draw was made. It was so bleak that Christopher O’Connell got in as a lucky loser despite falling in the first round of qualifying.

I expected to find that the level of the 2025 field was no better than what came before. (There are, certainly, some 250s with fields as strong as Munich’s this year.) But even with the injuries, the first edition as a 500 was a big step up. The median rank of players in this year’s field was 52.5, compared to last year’s 91. This year, 25 of the 32 main-draw entrants ranked in the top 100, 14 of them in the top 50. Last year, only 15 of 28 were in the top 100.

13. Andre Agassi is headed to the booth:

TNT Sports has hired eight-time Grand Slam winner Andre Agassi as a studio commentator for the network’s coverage of the French Open this year. Agassi, who won the 1999 French Open and was runner-up three other times, will be a studio analyst during the semifinal and championship rounds at Roland-Garros. In 2024, TNT Sports reached a 10-year, $650M agreement with the French Tennis Federation to add the French Open to its portfolio of premium sports rights in the U.S.

Always great to see more voices–especially the very best players–do commentary. My impression is that commentary is extremely difficult, and most former players quickly start repeating themselves. I’d rather hear a wide range of perspectives, which means every new voice is welcome.

14. I enjoyed this rundown of the evolution of Wimbledon qualifying, 1919-1925.

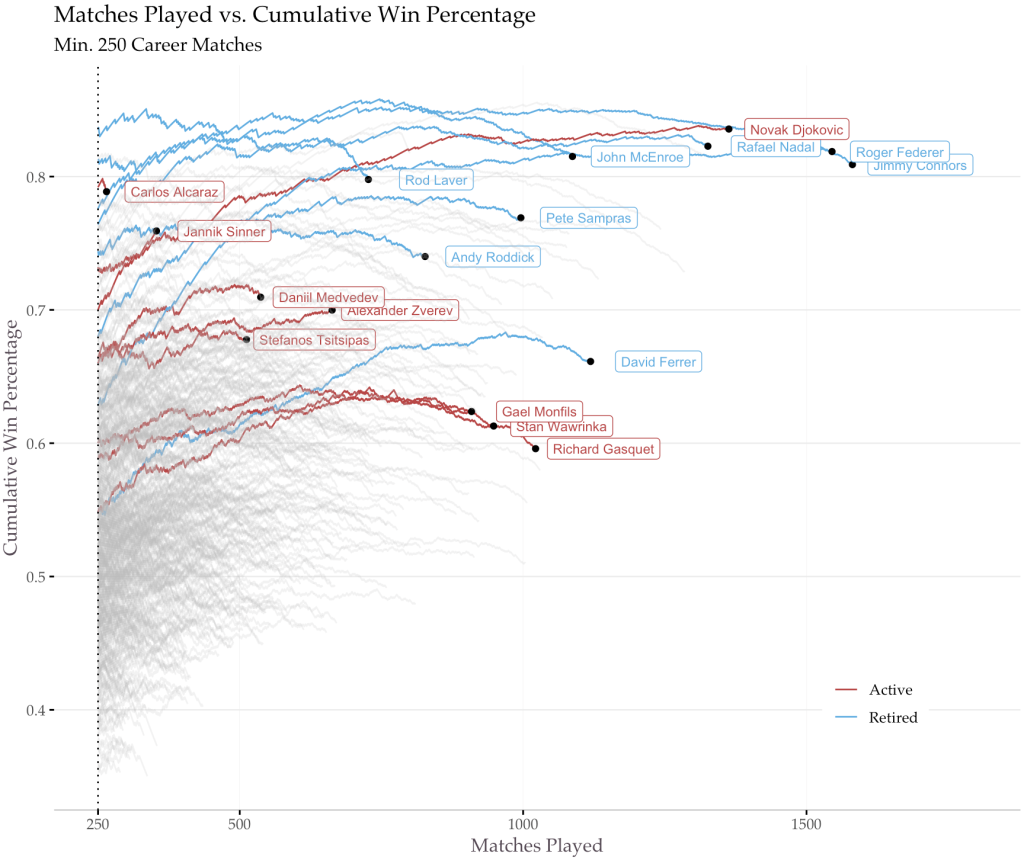

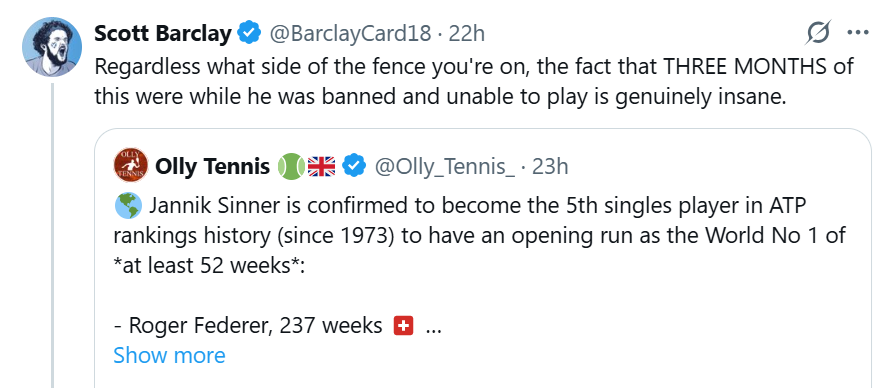

15. Jannik Sinner is now guaranteed to have 52 weeks at ATP #1:

This, including a three-month suspension.

Elo agrees that Sinner remains the best player on tour, even though my algorithm applies a 100-point penalty to players who miss so much time.

Another way of seeing Sinner’s dominance is to compare the current men’s and women’s lists. No, the lists aren’t meant to be compared, but after decades in which the top women built higher Elo ratings than men–mostly because the level of competition wasn’t as deep–they’ve begun to look similar. For instance, #4 to #10 on the men’s and women’s lists have nearly identical ratings.

Well, even after the 100-point penalty, Sinner is still 50 points ahead of any other man, and 40 points ahead of Aryna Sabalenka.

16. More high-quality Challenger streaming! It’s fantastic that all Challenger matches are streamed, but I have a hard time staying interested in the single-camera broadcasts. This will be so much better.

Also, I continue to be thankful for the Masters events that stream qualifying, as Madrid did this week. Now, WTA, take the hint already!

17. Speaking of Challenger-level women’s tennis… Raluka Serban won her first-round match in Bogota against Nuria Parrizas Diaz despite committing 22 double faults. She hit 48 second serves and missed nearly half of them. On the bright side, she won 20 of the remaining 26 points.

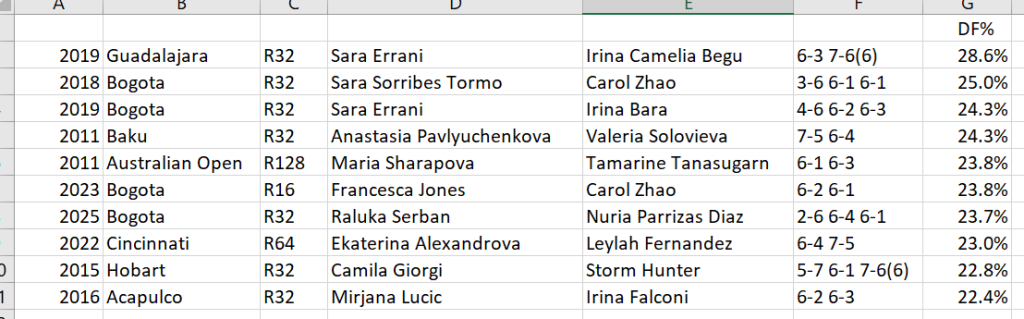

My friend Kees, who charted the match and passed along the tidbit, asked if anyone had ever won a match with such a high double-fault percentage. My WTA matchstats data goes back to about 2010, and excluding retirements and lower-level Fed/BJK Cup matches, Serban does crack the top ten:

Sara Errani, of course, is our champion. Runner-up is the altitude in Bogota.

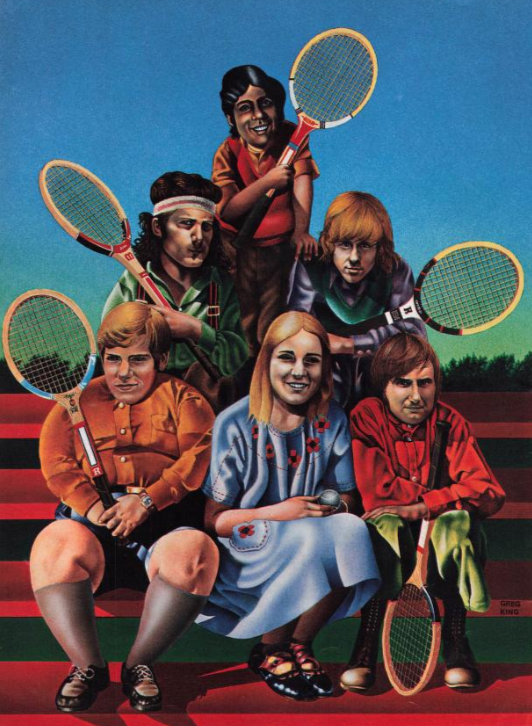

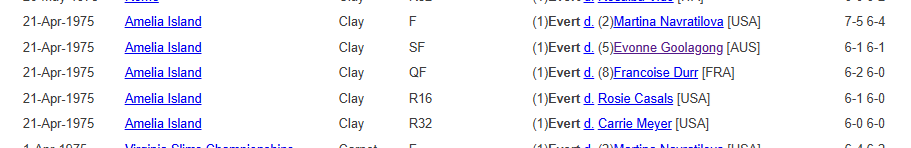

18. Even more history for you this month. Fifty years ago this week, Chris Evert waltzed to the Family Circle Cup title:

The final took so long, Evert said, because her mind was elsewhere. Her on-again, off-again romance with Jimmy Connors was back on, and the pair was engaged. The day that Chrissie faced Martina, Jimbo was in Las Vegas, playing a million-dollar exhibition match against John Newcombe at Caesar’s Palace.

Connors suffered no such distraction. He shut down Newk in four sets, collecting around half a million dollars–equivalent to about $3MM today–for his efforts.

19. RIP Pope Francis. Or, as we in the tennis world knew him, the recipient of Juan Martin del Potro’s US Open-winning racket.

20. This month’s send-off music:

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: