Exactly one year ago, I updated Tennis Abstract with some missing 1970s and 1980s WTA tournaments. I tweeted this progress report:

I didn’t know it then, but it was the beginning of an all-engrossing project to massively increase the amount of historical women’s tennis data available–not just on TA, but in any organized, easily-accessible form.

In the last year, TA has gained nearly a quarter of a million women’s singles match results going back a full century, to 1921. We all now have the ability to browse through the results of players from the 1920s the same way that we do players of the 2020s. It’s incredibly cool, and it constitutes a huge step toward a better understanding of tennis history.

The state of play

Until last November, Tennis Abstract’s database of women’s results was built on a combination of what I was able to find from the WTA and ITF websites. For contemporary players and their predecessors from the last few decades, that was enough. But as my tweet indicates, it didn’t even encompass the 80 matches of the greatest rivalry in tennis history. The WTA site still doesn’t display records of many top-tier events from the 1970s.

With Evert-Navratilova squared away*, I went to work on the remainder of the Open Era. Thanks to the Blast From the Past forum and John Dolan’s book, Women’s Tennis 1968-84, I was able to add results for the entire Open Era, including qualifying rounds and challenger-level events.

* I now have 81 of the 80 Evert-Navratilova matches, including one exhibition.

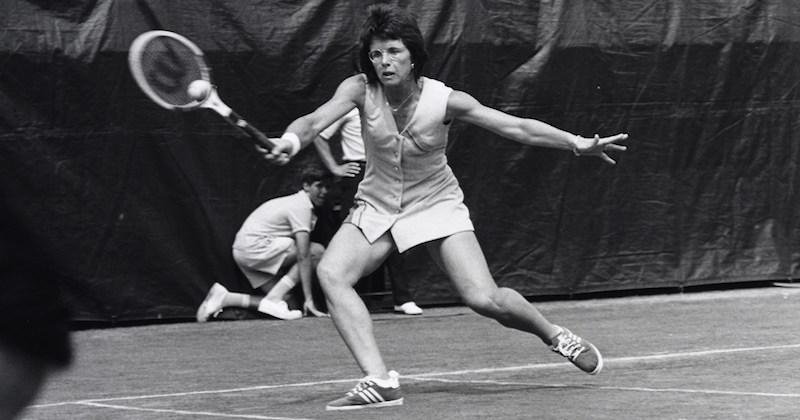

Of course, top-flight women’s tennis didn’t begin out of nowhere in 1968, and once you can look at a few thousand matches from 1968 and 1969, curiosity begins to take hold. Margaret Court and Billie Jean King began their careers in the early 1960s, so wouldn’t it be nice to know exactly what they were up to for the better part of the decade?

The amateur era

However incomplete the historical record was for the 1970s, it was considerably worse before 1968. Wikipedia has grand slam draws and not much else. The heroes of the next phase are the contributors to tennisforum.com’s Blast From the Past section.

Blast contains extensive results for the entire history of women’s tennis, accumulated over two decades. It’s a truly incredible project, the sort of thing that no single person could’ve accomplished on their own. The year-by-year forum entries have complete singles draws for notable events (and many minor ones), and doubles and mixed doubles finals for most tournaments. To give you an idea of just how serious an undertaking this is, the forum topic for 1930 has over 5,000 singles match results from that season alone. A small group of tireless contributors typed all those up.

The downside of typed-up results is that they are very cumbersome to search. There are other issues, like inconsistent player names, since a single player might go by a maiden name, a married name, abbreviations or initials, and nicknames over the course of her career. (Not to mention typos!) To address those inherent limitations, you need a proper database.

247,000 singles matches

That database is what I’ve been doing for the last year. Working backwards one year at a time, I’ve pushed the dataset back to 1921, which–incidentally–gives us almost the entire career of Helen Wills. The project has involved hundreds of hours of proofing, player matching (all those name variations I mentioned), and lots of good old-fashioned data entry. While I’ve developed some automated tools to speed things up, there’s a limit to how much a process like this can be accelerated.

In the process, I’ve jumped over to the newspaper-research side of things, filling in the gaps of the Blast From the Past forum’s extensive coverage. My best estimate is that I’ve added about 20,000 results to the dataset, mostly for North American events before World War II. It’s fascinating if occasionally mind-numbing, and looking at old newspapers can be distracting enough to threaten my progress entirely.

All told, from 1921 to the mid-1990s, the Tennis Abstract database has gained almost a quarter of a million matches since that tweet last year, and it now encompasses a reasonably complete view of the final 47 years of the amateur era.

How you can dig in

Amateur-era players are shown on Tennis Abstract in a nearly identical manner to that of current players. In addition to Wills, here are links for Althea Gibson, Maureen Connolly, and Simonne Mathieu. You can find most of these players using the search box or via the exhaustive yearly summary pages, like these for 1925, 1945, or 1965.

Player and yearly summary pages show Elo ratings for women who played a certain number of matches. There’s a ton of information beyond the simple list of results.

For those of you who would like to do your own calculations, ratings, or other data exploration, I’m also releasing all the raw data on GitHub. Releases of new seasons usually happen several weeks later than the results first hit the TA website, so the GitHub repo currently goes back to 1927. The format is the same from 1927 to the present, so if you’ve worked with my data before, you’ll find the historical results to be in a familiar format.

Black tennis

An interest that has grown into a sizable side project is the history of segregated tennis. In most histories, Black tennis starts with Althea Gibson. Yet the American Tennis Association and various local outfits created a thriving tennis scene for Black players as early as the 1910s, long before the USLTA (now USTA) integrated their events.

Beyond contemporary newspaper writeups, results from Black tournaments have rarely been published. Using sources such as the Chicago Defender, the New York Amsterdam News, and the Baltimore Afro-American, I’ve been able to reconstruct draws, discover forgotten tournaments, and start to piece together career records for women who weren’t allowed to compete elsewhere.

One fascinating place to start is the player page for Ora Washington, the greatest Black player of the pre-Althea era. She spent her winters playing basketball so well that she’s now a member of that sport’s Hall of Fame. Based on her record as a tennis player, the folks in Newport ought to honor her tennis exploits as well.

Challenges and caveats

This is the sort of project that, quite simply, will never be finished. Yes, we can close the door on certain tournaments, such as most majors and certain other events with top-flight competition. But there’s no clear line between amateur era tournaments worth including and worth skipping, so there’s always more to hunt down. And even some of the events of the greatest historical interest–like the national tournaments of the aforementioned American Tennis Association–are poorly represented in the dataset, simply because I can’t find more than a few match results.

Another central challenge has to do with names, and it gets worse the further back we go. Newspapers often identified players only by their last name, sometimes including a first initial. Is this “M Smith” in a London-area draw in the 1920s the same as that “M Smith” in a different London-area draw in the 1920s? I have no idea! There are hundreds of questions like this, and I can’t imagine we’ll ever answer even a fraction of them. Newspapers also made lots of mistakes. Even an august publication like the New York Times would occasionally mix-and-match the first names of players. “Madelon Westervelt” is surely the same as “Madeleine Westervelt,” but is “Margaret Westervelt” the same person? (In this case, probably, but you get the idea.)

When you combine spotty source data, hand-made tools to help automate things, and the bleary-eyed researcher that I often am, you end up with bugs. Lots and lots of bugs. If you poke around the site for long, you’ll surely find some. When you do run across something that looks wrong, feel free to let me know, and please be patient. I want to resolve known bugs, but I also want a more exhaustive dataset. Balancing those two goals–along with other aims such as not alienating my family–often results in long wait times for bugfixes.

Thanks for reading all this far. I’ll be writing more about pre-Open Era topics in 2022, and when I’m not doing that, I’ll be pushing back in the 1910s and beyond.