On Tuesday, Matteo Berrettini and Alexander Zverev slugged out a 48-shot rally, the longest of the season so far. It came at 5-5, deuce, in the deciding set. Berrettini won it, opening the door for a final break of serve and a hold to seal the match.

At almost no stage of the epic point would we have picked the Italian to come out on top. First, it was a Zverev service point. The server’s advantage doesn’t last 48 strokes (or anywhere close), but it gives him an edge for the first several shots. Second, the German is more of a grinder. On reputation, anyway, he’s the easy pick in a marathon rally. Finally, Berrettini thrice found himself digging out of a corner with a defensive chip, a shot that is often an invitation for the man across the net to end the point, even on slow clay.

Yet long rallies are not well understood. Once the seventh or eighth ball was struck, the odds were only barely in Zverev’s favor. And Berrettini’s chip recoveries, while from defensive positions, didn’t give his opponent much of an advantage.

It’s easy to picture a strong baseline player outmuscling a weaker one, steadily building up an edge until he is finally able to put the point away, whether on the 8th, 28th, or 48th shot. But while point construction remains a valuable skill, there’s nothing inexorable about it. As we will see, even a mediocre defender can cancel out those efforts and put the rally back on equal footing.

By the time the stroke count hits double digits, the momentum has probably flipped or reset. By 48 shots, there have been several such shifts. It’s no longer a battle for supremacy but a fight for survival, with an ending that might as well be a coin flip.

Prolongation

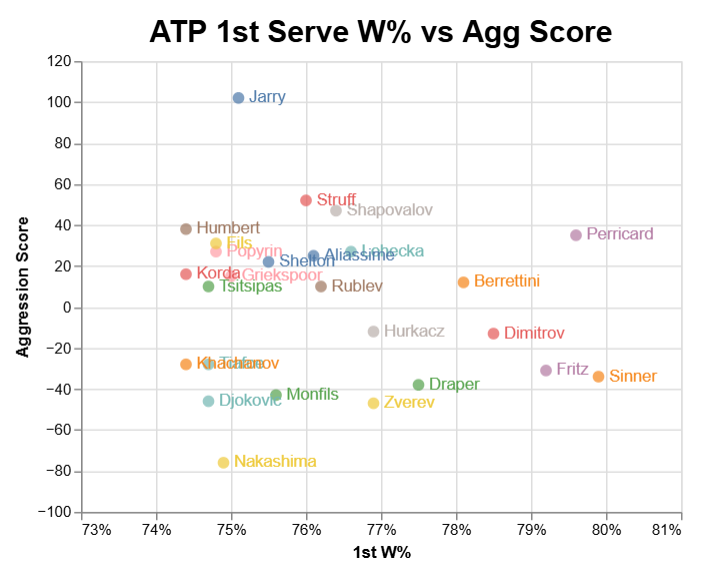

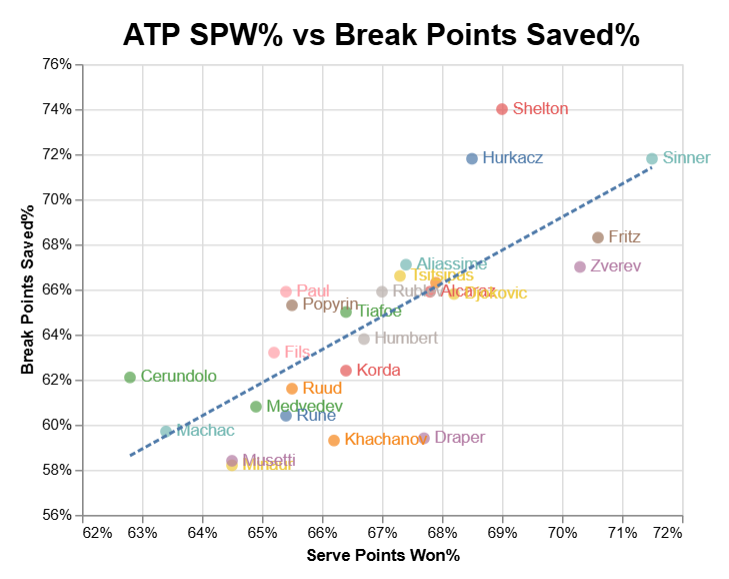

Virtually everyone on tour wins between 40% and 60% of their double-digit rallies. Based on charted matches from the last 52 weeks, Zverev stands at 51%, with Berrettini at 47%.

Even in Tuesday’s match itself, the outcome of the marathon point was no outlier. The Italian won 12 of 22 in the ten-plus category. He even won the seven- to nine-shot category by the same margin.

The players we might think of as long-rally experts have a slightly different skill. They don’t win an overwhelming number of the long points (Casper Ruud: 49%, Lorenzo Musetti: 51%), but they are more likely to get there. Returners begin the point at a disadvantage, so the longer they stick around, the more likely they are to win the point. Zverev doesn’t win many more long rallies than Berrettini does, but he plays a lot more, and those 50/50 propositions are a better deal for him than, say, losing the point six strokes earlier.

This might sound familiar: I wrote about Daniil Medvedev’s rally-stretching skill about a year ago. Zverev rated as highly as the Russian in terms of dragging points onto equal terms.

Here is how the returner’s odds look at each stage of the rally, based on clay-court matches since 2020 in the Match Charting Project. The table shows the returner’s win rate when he puts each shot in play:

Shot # Point W% 2 (vs 1st sv) 44.9% 2 (vs 2nd sv) 52.5% 4 52.7% 6 54.5% 8 55.1% 10+ 56.6%

Short version: The longer you last, the better your chances. That 56.6% for shot number ten (and beyond) really means something more like 50/50. A pro who has just put the ball in play has a better chance of winning simply because he hasn’t just made an error, and the other guy might. In a very long, evenly-balanced point, the odds will bounce between 60% and 40% in favor of the guy who just landed his last shot.

Recovery

If you haven’t seen the rally, jump to 1:22 here:

(If you have already seen it, go ahead, click, nobody’s gonna know.)

Zverev’s first real move comes on the 25th shot of the rally (~1:56 in the clip), when he sends a backhand up the line. Berrettini had been cheating to his backhand side, so he’s not ready for it. He’s forced to play a forehand chip to stay alive.

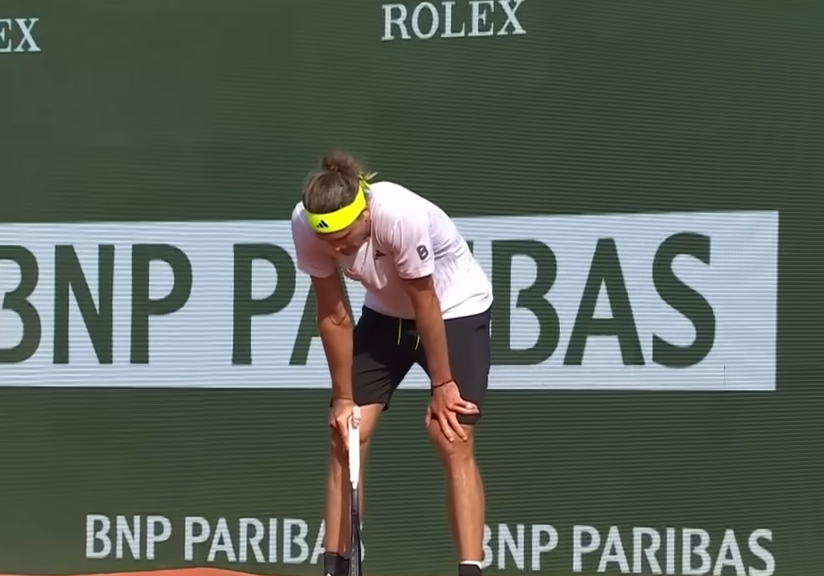

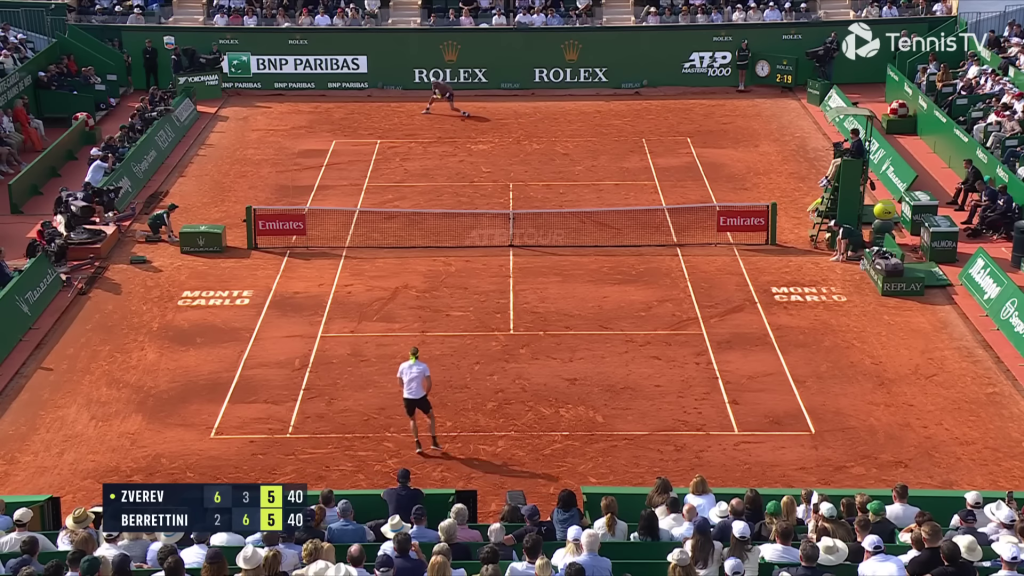

This is Matteo’s position (at the far end) to hit shot #26:

Wild guess: If you find every shot that looks like that, you won’t find many guys who come back to win the point.

Yet Berrettini not only kept the ball in the court, he dropped it within inches of the baseline. The two- or three-shot sequence that Zverev had in mind was now off the table. Maybe the Italian didn’t boost his point-winning odds back up to the standard 56.6%, but he came close.

It’s no secret that depth matters. I’m going to go one step further and say: However much you think depth matters, it is more important than that.

Take long-rally shots in general. The Match Charting Project has depth for over 7,000 shots (again, on clay since 2020) that were hit down the middle on the 10th stroke or later. Here is the shotmaker’s chance of winning the point, depending on depth:

Depth Point W% Shallow 41.3% Deep 45.7% Very deep 49.4%

(“Shallow” is anything in front of the service line. “Deep” is behind the service line, but closer to the service line than the baseline. “Very deep” is closer to the baseline.)

Remember that most players end up between 40% and 60% on long points, and Zverev is barely above neutral. The difference between a shallow groundstroke down the middle and a very deep one is almost as dramatic as the gap between a poor long-rally player (say, Nicolas Jarry) and Zverev.

Back to the Monte Carlo slugfest: By dropping his forehand near the baseline, Berrettini’s chip recovery almost literally neutralized the point that Zverev had just tilted heavily in his own favor.

And again

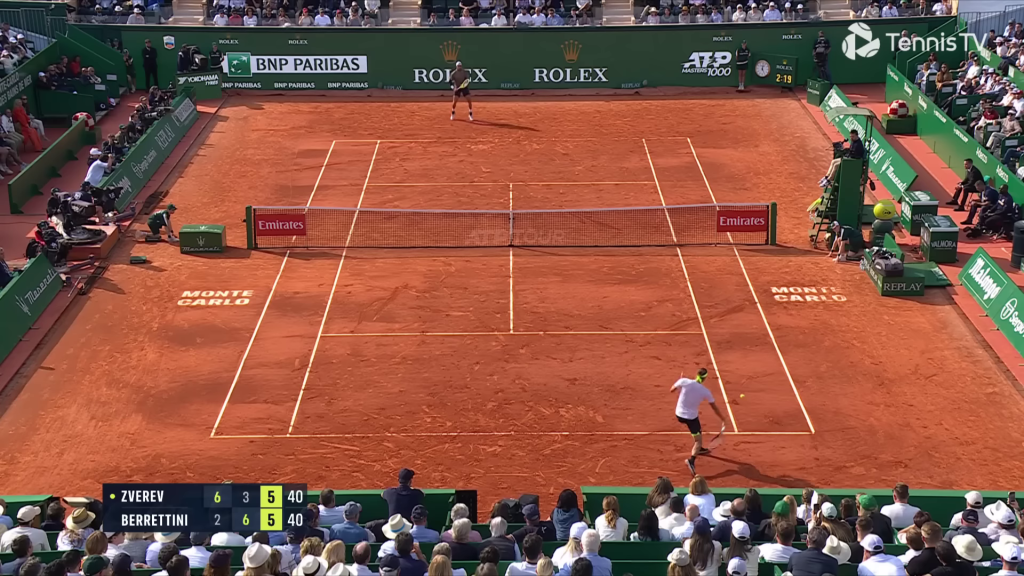

The German knew he was on to something: He tried essentially the same play two more times in succession. His 31st and 35th shots were both backhands up the line, and an increasingly-gassed Berrettini was leaning the wrong way again. (And again.)

But twice more, the Italian chipped his way out of trouble. His second hail mary was even better than the first: He not only dropped it very deep, he put it in Zverev’s forehand corner. In other words, he bought himself some time to recover, and he limited his opponent’s ability to keep peppering him wide to the backhand.

Let’s consider the role of depth for slices, including chips like Berrettini’s. Here is the winning percentage after landing a slice in a long rally, separated by depth and whether the shot was down the middle:

Depth Slice-middle W% Slice-corner W% Shallow 34.7% 48.6% Deep 39.3% 43.8% Very deep 39.6% 51.8%

As you’ll see, the very deep, down-the-middle slice isn’t as effective as the typical very deep shot. In the case of Berrettini’s 26th shot, I think his odds were closer to 50% than 40% because it was so deep. But more to the point of his second recovery, on his 32nd shot, the very deep slice to a corner puts him above 50/50.

Point neutralized, again.

Endgame

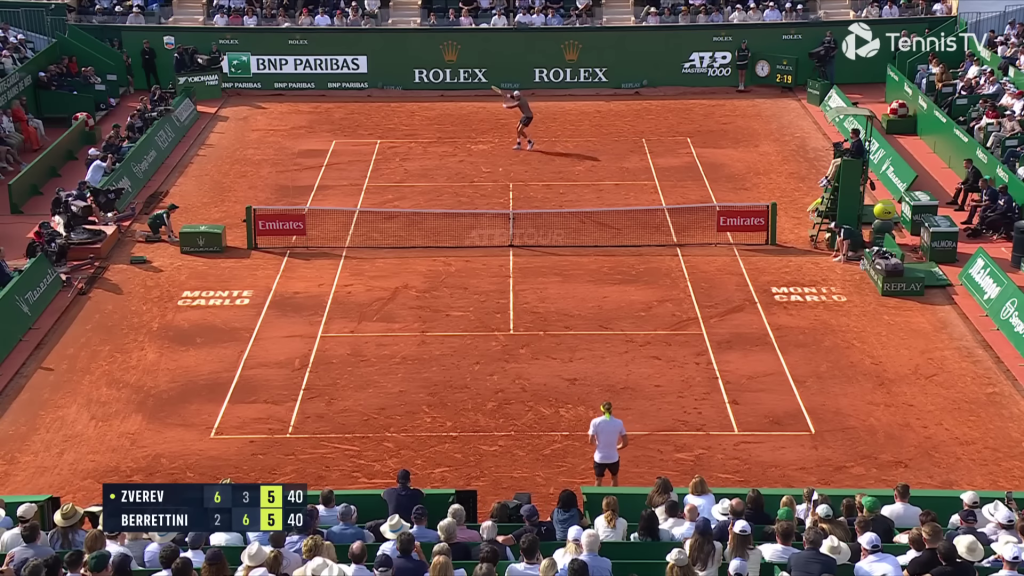

Ironically, after all of Berrettini’s digs, Zverev the grinder failed to match him. The 46th shot was a strong down-the-line backhand from the Italian. Zverev, accustomed to seeing slices from that wing, lost a split-second of reaction time. He had to chip to stay alive, but his attempt at a neutralizer wasn’t so deep. It barely cleared the service line, right in the middle of the court.

Matteo, master of the serve-plus-one, puts away balls like these in his sleep:

This rally, like most long points, ended up hinging on survival ability. Zverev did a lot of things right, forcing his opponent to play from his weak side, opening up space, attacking that space … and then going at it again when it didn’t work the first time. But on a clay court–especially one as slow as Monte Carlo–the defender always has a chance.

Or as your youth tennis coach might have said: Just make one more ball.

The pro equivalent: Yes, make one more ball, and be sure to hit it deep!

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: