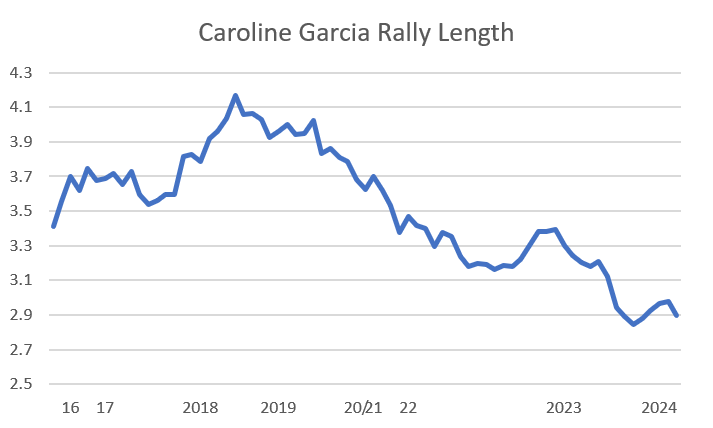

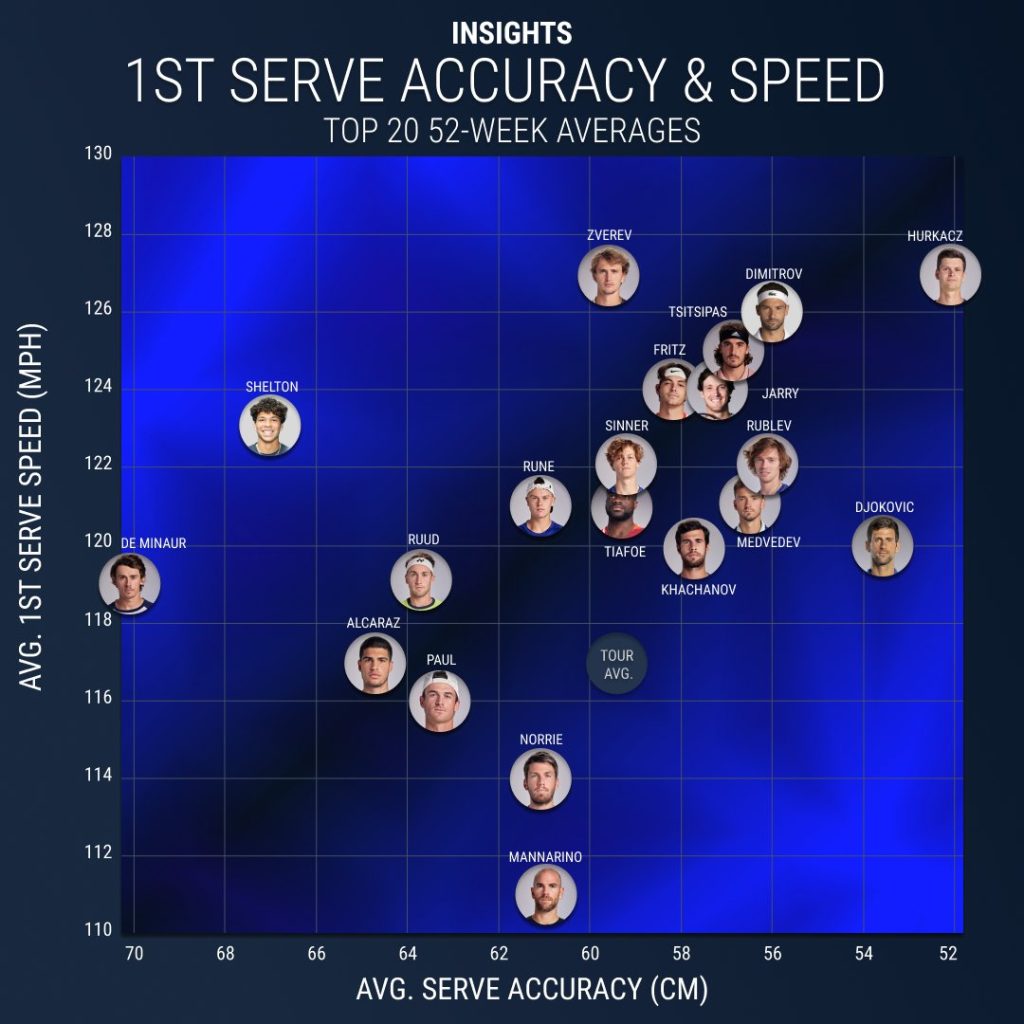

Last week, Tennis Insights posted a graphic showing the average first serve speed and accuracy–distance from the nearest line–for the ATP top 20. There’s a ton of fascinating data packed into one image.

Hubert Hurkacz is fast and accurate, Novak Djokovic is nearly as precise, and Adrian Mannarino defies logic as always. The most noteworthy outlier here, especially just after his run to the Rotterdam final, was Alex de Minaur. The Australian gets plenty of pop on his first serve, hitting them faster than tour average, if slower than most of the other men in the top 20. This comes at a cost, though. As one of the shortest guys among the elite, he doesn’t hit the lines. He’s by far the least accurate server in this group:

Precision is great: It’s certainly working for Hurkacz and Djokovic. But everything is a tradeoff. Any pro player could hit more lines if there was no reason to serve hard. Or vice versa: If the goal was simply to light up the radar gun, these guys could add miles per hour by aiming at the middle of the box. Standing a modest six feet tall, De Minaur is even more constrained than his typical peer. No technical tweak is likely to move him into Hurkacz territory. He might make small improvements or swap some speed for more accuracy.

Small gains would be enough, too. De Minaur wins fewer first-serve points than the average top-50 player, but in the last 52 weeks, he has outpaced Carlos Alcaraz, Holger Rune, and Casper Ruud. He trails Alexander Zverev by about one percentage point. This isn’t Sebastian Baez (or even Mannarino) we’re talking about. Whatever the cost of de Minaur’s inaccuracy, he’s able to overcome it. It’s just a matter of what gains he could reap by making returners work a bit harder.

Here’s the question, then: How much does accuracy matter?

Speed first

For this group of players over the last 52 weeks, speed is by far the most important factor in first-serve success. Speed alone–ignoring accuracy or anything else–explains 72% of the variation in first-serve points won. Accuracy alone accounts for 43%. (The players who are good at one thing are often good at others, so most of those 72% and 43% overlap.) 43% might sound like a lot, but isn’t that far ahead of something as fundamental as height, which explains 33% of the variation.

Surprisingly, precision is even less critical when it comes to unreturnable first serves. Using unreturned serve counts from Match Charting Project data, accuracy explains just 30% of the variation in point-ending first serves, less than we could predict from height alone. (Speed alone explains 60% of the variation in unreturned serves.) I would have expected that accuracy would play a big part in aces and other unreturned serves, since a ball close to the line is that much harder to get a racket on. But while precision may increase the odds of any individual serve going untouched, average precision isn’t associated with untouchable serving.

The story is the same for any metric associated with first-serve success. Speed matters most. There’s immense overlap between the factors I’ve discussed: Taller players find it easier to hit the corners, and all else equal, they take less of a risk by hitting bigger. There is probably some value of height that isn’t captured by speed or accuracy, such as the ability to put more spin on the ball, but the main benefit shows up on the radar gun.

To tease out the impact of each variable, I ran a regression that predicts first-serve points won based on speed, accuracy, and height. The results should be taken with an enormous grain of salt, since we’re looking at just 20 players, some of them the game’s most outrageous outliers. Still, the findings are plausible:

- Speed: Each additional mile per hour translates to an improvement of 0.43 percentage points in first-serve points won. (1 kph: +0.27 first-serve points won)

- Accuracy: Decreasing distance from the line by 1 cm results in an improvement of 0.2 percentage points in first-serve points won.

- Height: At least for these twenty players, the value of height is entirely captured by speed and accuracy. The margin of error for the height coefficient spans both positive and negative values. It is unlikely that height is a negative, though I suppose it’s possible, if speed and accuracy capture the height advantage on the serve itself, and height is a handicap on points that develop into rallies. Either way, the impact is minor, if it exists at all.

Approximately, then, one additional mile per hour is worth the same as two centimeters of accuracy. The height of the graph–110 to 130 mph–represents a variation of nearly 9 percentage points of first-serve points won. The width–70 to 52cm–represents a range of 3.6 percentage points. Broadly speaking, speed remains more important than accuracy, though a particular player might find it easier to improve precision than power.

Just one example of what the numbers are telling us: De Minaur has won 72.8% of his first-serve points over the last year, compared to the top-ten average of 75.3%. If this model were to hold true–a big if, as we’ll discuss shortly–that’s a gap he could close by improving precision by about 12 cm, to a tick better than tour average.

Drowning in caveats

For every question we answer, we’re rewarded with ten more questions.

I’m most interested in the choices that individual players could conceivably make, and the analysis so far offers only hints to that end. For this group of servers, we can say that a player who serves faster will win more points than his slower-serving peers. But we don’t know whether a specific player, if he was able to juice his serve by a mile or two per hour, would enjoy the same benefits. Hitting harder, or placing the ball more accuracy, is better, but by how much?

(I dug into the speed question way back in 2011 and found that one additional mile per hour–for the same player–was worth 0.2 percentage points. More recently, I found that for Serena Williams, an additional mile per hour was worth 0.5 percentage points. One of these days I’ll revisit the initial study with the benefit of many more years of data and perhaps a bit more wisdom.)

De Minaur was unusually precise in Rotterdam. Another Tennis Insights graphic indicates that his accuracy improved to about 55 cm for the week, an enormous gain of 15 cm from his usual rate, even more remarkable because his average speed was a bit quicker as well. (Playing indoors probably helped.) The model suggests that 15 cm is worth three percentage points. His boost of two miles per hour should have been worth nearly one more percentage point itself. Yet he won “only” 73.9% of his first-serve points–about one percentage point better than his non-Rotterdam average.

It’s just one week, so it isn’t worth fretting too much over the discrepancy. Still, it illustrates the value of the data we don’t have. (By “we,” I mean outsiders relying on public information. The data exists.) If we knew de Minaur’s accuracy and speed for every match, we could figure out their value to him specifically. Perhaps an uptick of one mile per hour is worth 0.43 percentage points only if you start serving like the players who serve faster–guys who are generally taller and can put more slice or kick on the ball. Those weapons aren’t available to the Aussie, so a marginal mile per hour may be less valuable. For him, accuracy might have a bigger payoff–relative to speed–than it does for other players. We just don’t know.

Sill, we’ve extracted a bit of understanding from the data. We’ve seen that accuracy translates into more first-serve points won, and we have a general idea of how many. De Minaur showed himself capable of hitting the lines as precisely as Andrey Rublev or Grigor Dimitrov, at least under a roof for one week. Just half that improvement, if he could sustain it–even if he didn’t get the full gains predicted by the model–would shore up a mediocre part of his game and lay the groundwork for a longer stay in the top ten.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: