Jelena Ostapenko is now 6-0 against Iga Swiatek. Their first meeting doesn’t really count: It was on grass, and Iga was 18. Since then:

One was close, and Swiatek picked up a set in two others. These are (usually) not blowouts. But most of the time Iga faces an opponent outside the top 20, it is a blowout–in the other direction.

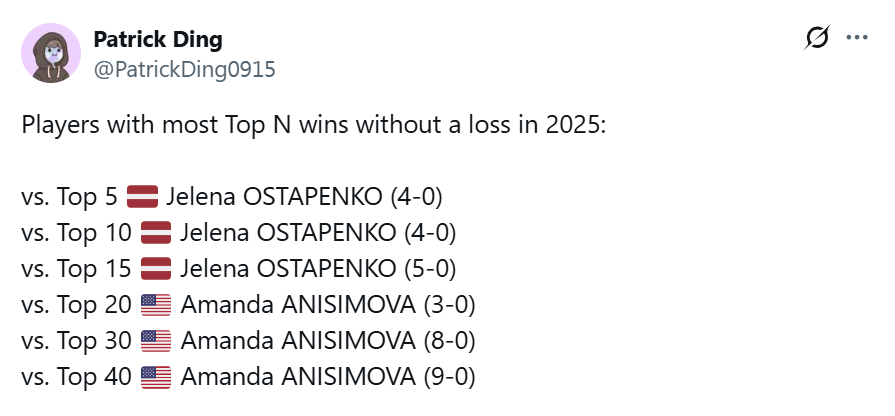

Ostapenko is a special case. No one on tour is more aggressive. Her make-or-break style, standing inside the baseline and swinging for winners even on service returns, turns every match into something more like a coin flip. If her aim is off, she can lose to anyone. By the same token, she’s the worst opponent for a top seed to draw in the middle rounds:

Career, Ostapenko has 25 top-ten wins, 21 of them when she was outside the top ten herself. It’s an exaggeration to say that her opponent doesn’t matter, but opponent matters less to the Latvian than to probably anyone else on tour.

Keep it simple

It’s tempting to go straight to the mental explanation: Ostapenko has gotten into Iga’s head, etc. That might explain why the head-to-head is 6-0 instead of 4-2 or 5-1. But there is a more concrete basis for the fact that the underdog keeps coming out ahead.

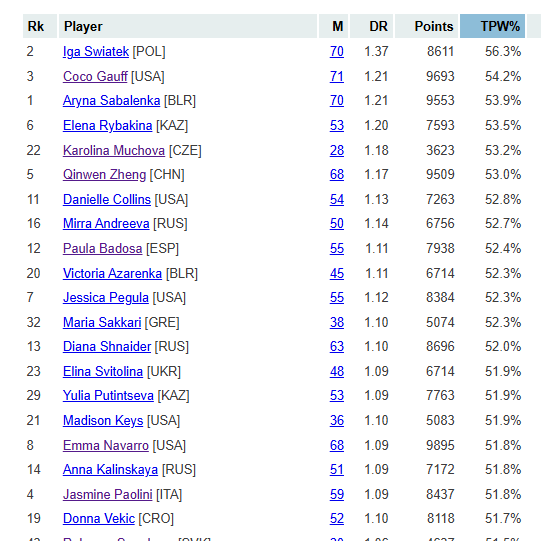

One of Swiatek’s lesser-known assets is her ability to win serve points. While she doesn’t have the best serve on tour, her opening delivery is quite fast, she rarely misses, and it sets up the rest of her game to finish off points. Over the last 52 weeks, she has held 79% of her service games, more than any other WTA player: Yes, even Aryna Sabalenka.

In their last five meetings, Ostapenko has broken her 31 times.

Against everybody else, Iga gets her share of service winners, and when the ball comes back, her unparalleled baseline skills keep the odds in her favor. Though she can rally with the best of them, she keeps points relatively short. Her serve points average 3.8 strokes, compared to tour average of 4.2.

Against Ostapenko on Saturday, her average serve point lasted 2.8 shots.

Another way to see the Penko effect is to look at the horrible things she does to Swiatek’s top-line serve numbers:

Matches 1stIn 1st W% 2nd W% Last 52 64.9% 68.3% 50.3% vs Penko 57.8% 51.8% 45.7%

Among the WTA top 50, Iga ranks in the top dozen for all three of those stats. The Latvian turns her into a wholly ineffectual version of herself. (In my earlier piece about Ostapenko, I wrote that she turns the rest of the tour into Madison Brengle. Even Iga!)

52% of first-serve points won is atrocious. No top-50 player stands below 57%. Sara Sorribes Tormo is the only woman who can compare. 46% isn’t quite so dire: Elise Mertens typically plays at that level, to take one example. But it’s a marked decline from Swiatek’s usual standard.

If you want to make case that Ostapenko has gotten into Iga’s head, the first-serve-in rate is one place to start. There is some tactical basis for taking more first-serve risks against a free swinger. But in this case, they don’t seem to pay off at all. That dreadful 52% win rate on first serve points is the result of hitting them bigger! Iga took more chances on second serves as well. She is typically one of the stingiest women on tour when it comes to double faults, but she piled up eight of them on Saturday.

The clay conundrum

I intended to write a version of this piece back in February, when Ostapenko trounced Swiatek in Doha. Though I missed my chance, I intended to make clear that Iga couldn’t beat her nemesis on hard courts.

And here we are, two months later. Ostapenko leads the clay-court head-to-head, 1-0.

Sort of. Stuttgart’s conditions are hardly those of Rome or Roland Garros. The tournament is held indoors, and the surface doesn’t behave like the crushed brick in Paris. Big servers have traditionally done better in Stuttgart than elsewhere on European clay. Ashleigh Barty won the title in 2021, and both Linsday Davenport and Maria Sharapova three-peated. Iga is a two-time champ as well, but not because the surface is particularly favorable.

Ostapenko scored her latest “upset,” then, on a relatively fast dirt court, one of that doesn’t give Swiatek’s topspin the big bounce it gets on traditional clay. A lower bounce lets the Latvian step in and swing away, much like she does on hard.

On the other hand, Penko is far from hopeless on the slow dirt. She beat Simona Halep to win the 2017 French Open! Worse, from Iga’s perspective, surface speed doesn’t seem to hinder her game style. Here are the rally lengths from the last few “slow clay” Ostapenko performances logged by the Match Charting Project:

Match Result RallyLen 2024 Rome L vs Sabalenka 2.6 2023 Roland Garros L vs Stearns 2.7 2023 Roland Garros W vs Martincova 3.4 2023 Rome L vs Rybakina 2.9

It’s not the most instructive sample–Ostapenko vs Sabalenka is going to come out under three shots per point on a court made of glue–but it’s clear that the Latvian doesn’t morph into Chris Evert when the conditions change.

At a certain level of aggression, surface just doesn’t matter that much. While Ostapenko doesn’t have an elite serve, she successfully targets the corners, opening up space for easy (for her) winners on the next shot. She takes such breathtaking risks that opponents sometimes are still leaning the wrong way as her shot finds a corner. Slow clay gives players an extra split second to react and respond. A split second is not enough to negate the Ostapenko barrage.

What to do?

Swiatek is one of the best players in the world–indeed, she already ranks among the all-time greats. It can’t really be hopeless.

There are basically two options: Stop Ostapenko from playing her game, or play Ostapenko’s game, but better.

In Stuttgart, Iga seemed to attempt the second. As we’ve seen, she took more chances on both first and second serves, though that tactic didn’t work out. She hit service returns harder, aiming for lines rather than relying on her topspin to give her a Nadal-esque margin of safety on groundstrokes.

At times, it worked. Swiatek hit nearly as many winners as Ostapenko in the second set. When the Latvian lost her way a bit, Iga barely let her win a second-serve point, picking up nearly three out of four. Penko broke her six times, but Swiatek got four of them back.

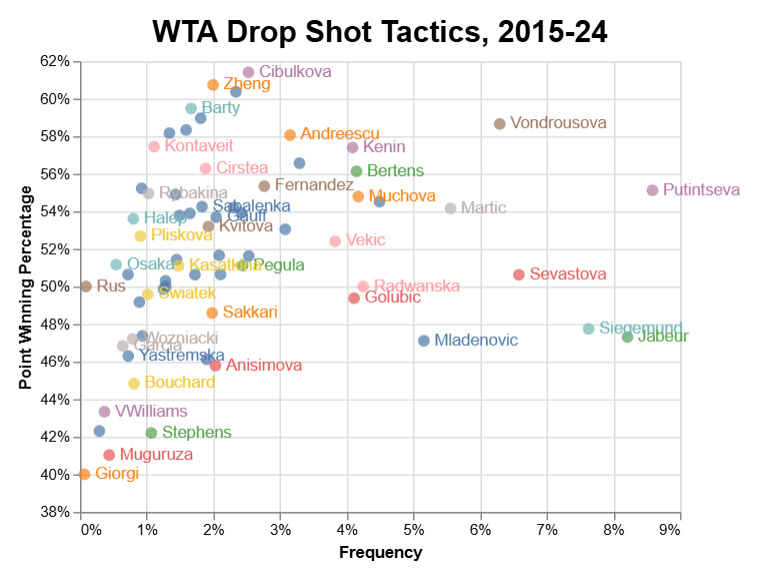

The play-like-Penko approach should ultimately stop the bleeding. This was the third time the women reached a deciding set; one of these times, the Latvian’s risk-taking will fail to pay off. Nearly everyone else on tour has picked up a win or two against Ostapenko: If Yulia Putintseva can do it, certainly Swiatek can as well.

Iga, though, would prefer something more than just continuing to flip the coin. Is there a way to consistently beat someone with such an outrageously dictatorial game style?

I’d love to give you a galaxy-brain answer here, but I don’t have one. (Wim Fissette hasn’t helped Iga find one either, so I certainly don’t have much of a chance.) At times on Saturday, Swiatek seemed to be trying to wear down the Ostapenko backhand. It is the Latvian’s weaker side, but it is still the source of numerous, often improbable winners. Riskier serving came up empty. The topspin is worthless, though it may have its place in more favorable conditions.

No one on tour owns Ostapenko the way she owns Iga. (Edit: Except Victoria Azarenka–thanks to several of you for pointing that out.) No style or set of tactics–except Vika’s, so far–stops her every time. Sabalenka had won all three meetings with the Latvian, then she managed just five games in yesterday’s Stuttgart final. Sabalenka is one of the few women who can out-hit anybody, but even that level of power isn’t enough to shut out Ostapenko.

The only player reliably able to defeat Penko is herself, and even she hasn’t managed it with Iga standing across the net. She may have another chance in just a few days: The two women are lined up to face each other in the Madrid fourth round. Ostapenko is a mere 5-7 at the event in her career, but she is surely salivating at the chance for another shot at her favorite victim.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: