Some players seem to play better in best-of-five matches. Maybe they are fitter than average, or they take time to get into the rhythm of a match, or they are particularly good at managing their preparation to peak for grand slams. There are many plausible explanations. I suspect most fans assume that there’s some kind of “best-of-five” factor that makes certain players better or worse than usual at the majors.

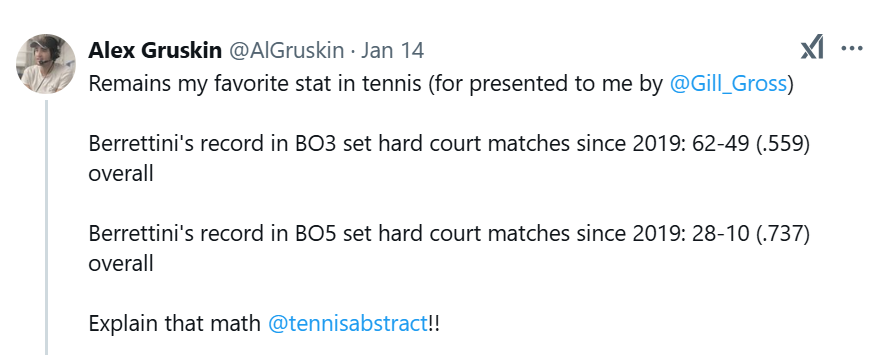

I took a first crack at the question during the 2014 Australian Open. Then, Jo-Wilfried Tsonga stood out as a best-of-five specialist. With more data and better tools, it’s time to try again. Gill Gross and Alex Gruskin teed it up:

Challenge accepted!

Note that the stat here is awfully specific: hard-court matches since 2019. Matteo also lost to Holger Rune in the second round yesterday, so the numbers have slightly changed. We’ll come back to this particular puzzle in a bit.

First, it’s important to remember that many players should have better records in best-of-five than in best-of-three. It’s the same reason that in other sports, best-of-five (or best-of-seven) series are more likely to go to the favorite than more luck-bound best-of-threes. Given more sets, players have more time to turn things around. The stronger of the two competitors is more likely to do so.

A fantastic illustration of this comes, appropriately enough, from the (all-surface) career numbers of Berrettini himself:

Format Set% Win% Best of 5 62.1% 68.9% Best of 3 62.0% 63.8%

The Italian wins sets at almost exactly the same rate, regardless of format. But the match win percentage is different. There’s still something to be explained: A player who wins 63.8% of best-of-three matches should, all else equal, win approximately 67% of best-of-five matches. Matteo has done better than that, but the format alone explains much of the gap.

Better at best of five?

Identifying players who outperform expectations requires that we define “expectations.” As usual, Elo makes it easy to do this. For every individual match, we can use the Elo ratings of the two men to generate probabilities that each will win.

For Berrettini at hard-court slams since 2019–excluding retirements and the 2025 Australian Open–I have him at 27-9, good for a 75% win rate. Based on pre-match Elo ratings, though, he “should” have gone just 22-14 (technically, 22.5-13.5), taking 62% of the contests.

That’s noteworthy but not astonishing: A player expected to win 62% of the time has about an 8% chance of winning at least 27 of 36 matches. Given the number of ATP tour regulars, it stands to reason that somebody would post a stat like that. We can’t cast aside the Italian’s case yet, because we haven’t talked about his best-of-three results. Again, I’m going to kick it down the page because I want to show you some other numbers first.

Before looking at the narrow set of 2019-24 hard-court numbers, let’s see how everybody fared at grand slams, on all surfaces, since 2000. Out of 154 men with at least 50 grand slam matches this century, here are the top dozen overperformers:

Player W-L W% Exp% Ratio Pablo Andujar 23-39 37.1% 27.9% 1.33 Denis Istomin 34-41 45.3% 34.7% 1.31 Frances Tiafoe 45-34 57.0% 46.2% 1.23 Mario Ancic 40-20 66.7% 54.4% 1.23 Victor Hanescu 29-35 45.3% 38.6% 1.17 Karen Khachanov 59-30 66.3% 56.6% 1.17 Simone Bolelli 25-32 43.9% 37.6% 1.17 Leonardo Mayer 33-38 46.5% 40.1% 1.16 Marat Safin 79-32 71.2% 61.5% 1.16 Nick Kyrgios 54-28 65.9% 57.0% 1.16 Bernard Tomic 40-35 53.3% 46.7% 1.14 Matteo Berrettini 49-20 71.0% 62.6% 1.13

The first percentage is actual win percentage, followed by expected win rate (based on Elo ratings). The ‘Ratio’ column is simply the ratio of actual to expected. These are the guys who have played better at slams than their track records would have implied.

This ratio starts to identify overperformers, but we can go one step further. Sample size really counts here. It’s one thing to win seven of ten matches when you’re expected to win five. It’s wildly different to win 70 of 100 when you’re expected to win 50. The odds of the first are 17%, while the chances of the second are a fraction of one percent.

Since this next metric accounts for sample size, I’ve expanded our view to the 334 men with at least 20 slam matches since 2000. Here are the twenty players who have most defied the odds with their overperformance in best-of-five:

Player Record W% Exp% Ratio Odds Novak Djokovic 364-45 89.0% 84.3% 1.06 0.4% Rafael Nadal 304-41 88.1% 82.9% 1.06 0.5% Tennys Sandgren 16-17 48.5% 27.6% 1.76 0.9% Marin Cilic 133-56 70.4% 62.4% 1.13 1.4% Stan Wawrinka 151-66 69.6% 62.4% 1.12 1.6% Marat Safin 79-32 71.2% 61.5% 1.16 2.2% Frances Tiafoe 45-34 57.0% 46.2% 1.23 3.5% Mario Ancic 40-20 66.7% 54.4% 1.23 3.6% Denis Istomin 34-41 45.3% 34.7% 1.31 3.7% Jo-Wilfried Tsonga 120-43 73.6% 66.8% 1.10 3.7% Karen Khachanov 59-30 66.3% 56.6% 1.17 4.0% Carlos Alcaraz 57-10 85.1% 76.5% 1.11 6.1% Nick Kyrgios 54-28 65.9% 57.0% 1.16 6.4% Tomas Martin Etcheverry 12-12 50.0% 33.1% 1.51 6.4% Lukasz Kubot 20-20 50.0% 37.3% 1.34 6.9% Pablo Andujar 23-39 37.1% 27.9% 1.33 7.3% Andrey Kuznetsov 18-21 46.2% 33.8% 1.37 7.4% Thomas Fabbiano 10-13 43.5% 27.7% 1.57 7.6% Matteo Berrettini 49-20 71.0% 62.6% 1.13 9.2% Joachim Johansson 15-8 65.2% 49.4% 1.32 9.5%

I’ll admit it, I mostly lowered the match minimum so that we could have a top five consisting of four slam winners and one Tennys Sandgren. Djokovic and Nadal don’t stand out in the “Ratio” category: They were expected to wins lots of matches, and they did. But not only that, they slightly exceeded expectations for a very, very long time. There’s only a one-in-two-hundred chance that a player expected to win 83% of matches would win 88% over such a long stretch.

Enter the skeptic

Even highlighting these outlier performances–many of them in the hands of players we’d expect to see on the list–it’s not clear whether there’s really a best-of-five factor. As noted, we’re working with a population of over 300 players. Three of them gave us one-in-one-hundred performances. Fewer than 10% turned in one-in-ten performances. Isn’t that what we’d expect?

This isn’t a laboratory: We can’t run tests on Novak Djokovic to see if he would keep winning at the same rate in his next 410 best-of-five matches. We certainly can’t do it 100 times to be sure. We can, however, wring a bit more from the data we have.

If there is a special best-of-five skill–above and beyond a player’s general tennis ability–we’d expect players to show it with some consistency. (If they didn’t, could we call it a skill?) Here are two tests to check whether it’s a skill:

- Career halves: Split each player’s list of best-of-five matches into halves. Tommy Paul, for instance, went 13-13 in his first 26 best-of-five matches–worse than expected. Since then, he’s won 19 of 27–better than expected. If there’s a best-of-five skill, we’d expect those numbers to be persistent. Sometimes they are, but in general, they are not. Statistically, there’s virtually zero correlation.

- Odd and even matches: Maybe career halves are the wrong way to do it: Players improve and tendencies change with age. Instead, take each player’s list of best-of-fives and put them in two buckets, one for the first, third, fifth, etc. matches on the list, the other for the second, fourth, etc. Different tack, same results: no reliable relationship.

To be clear, this doesn’t tell us that everyone’s results are a luck-driven mirage, or that no one has any noteworthy best-of-five skill. Across 350 or 400 matches, I’d bet that Djokovic and Nadal probably do. (Heuristic: If a trait is good, they probably have it.) But in general, a player who is winning more best-of-fives than expected is probably due for a correction. There’s no basis to expect the trend to continue.

The Berrettini double

With that bucket of cold water thrown on our dreams, let’s return to the head-scratcher we started with.

Hard-court matches since 2019. Here are the best-of-five overperformers, minimum 20 slam matches:

Player Record W% Exp% Ratio Odds Frances Tiafoe 27-12 69.2% 49.6% 1.40 1.0% Matteo Berrettini 27-9 75.0% 62.4% 1.20 8.1% Adrian Mannarino 15-12 55.6% 41.1% 1.35 9.3% Alexei Popyrin 13-11 54.2% 39.9% 1.36 11.2% Taylor Fritz 27-12 69.2% 58.6% 1.18 11.6% Novak Djokovic 52-4 92.9% 87.2% 1.07 13.9% Rafael Nadal 31-5 86.1% 79.7% 1.08 23.4% Daniil Medvedev 56-11 83.6% 79.5% 1.05 25.6% Pablo Carreno Busta 21-9 70.0% 63.1% 1.11 27.9% Marin Cilic 17-8 68.0% 60.9% 1.12 30.7%

Holy Tiafoe! Elo would have predicted a 50% win rate, and instead he went 27-12. Berrettini comes next, but by this metric, it’s a distant second. Only Tiafoe really stands out in this sample.

But wait–there’s more to the Gross/Gruskin puzzle. The Italian has not only overperformed at slams, he has notably underperformed on hard courts elsewhere. Excluding Challengers, retirements, and Davis Cup, Berrettini’s record is even more mediocre than the one listed above: It works out to 42-42. Elo would have predicted a 58% win percentage, not a mere break-even rate.

Of the 35 players with at least 20 hard-court slam matches in this span, only David Goffin more severely underperformed in best-of-three. Only Goffin, Jannik Sinner, and Gael Monfils posted more unexpected numbers in best-of-three. Berrettini is as odd in best-of-three as he is in the longer format, just in the opposite direction.

Using the “Ratio” numbers, we can compare best-of-five over- (or under-) performance with best-of-three, for a kind of “super-ratio.” While Matteo is unique is the unexpectedness of his two numbers, Tiafoe still comes out ahead:

Player bo5 Ratio bo3 Ratio bo5/bo3 Frances Tiafoe 1.40 0.98 1.42 Matteo Berrettini 1.20 0.86 1.40 Adrian Mannarino 1.35 0.98 1.38 Alexei Popyrin 1.36 1.07 1.27 Marin Cilic 1.12 0.91 1.23 David Goffin 1.04 0.86 1.21 Daniel Evans 1.12 0.97 1.15 Dominic Thiem 1.10 0.97 1.13 Davidovich Fokina 1.14 1.01 1.13 Taylor Fritz 1.18 1.05 1.13

The odds that Berrettini would give us such an unusual pair of stats are 0.3915%. Tiafoe’s number is 0.3969%. Let’s call it a tie.

Are we there yet?

After all this, I’m not sure that I’ve “explained” what’s going on here, per Gruskin’s request. We’ve seen that where best-of-five results differ from a player’s overall results, it’s mostly luck. I assume it’s the same with best-of-three. Maybe there are some additional factors in Berrettini’s case: Perhaps he’s more likely to play non-slams when he’s physically less than 100%.

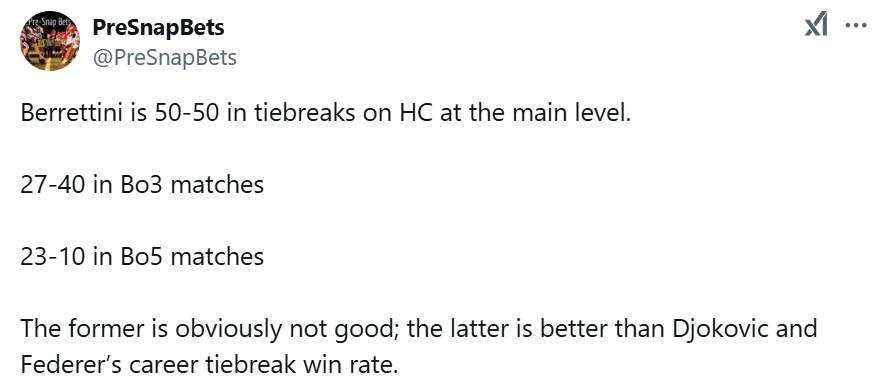

There’s also this:

Tiebreak records are definitely luck-driven. These splits account for much of the difference in Matteo’s match-level results. A few points here or there, and we wouldn’t be having this conversation. Or, more likely, we’d be overreacting to unexpected numbers from somebody else.

Poor Hubi

One last thought. We’ve looked only at overperformers so far. Of course, there will always be underperformers as well. Hubert Hurkacz has disappointed a bit at slams: 34-25 before the Australian Open, compared to an Elo-expected 37-22. The subset of hard-court slams since 2019, where you’d expect the big-serving Pole to excel, has been far worse.

In a dozen majors, Hurkacz has gone 14-12, a 54% win rate compared to an expected mark of 73%. The odds of such a wide gap are 0.9%, slightly more extreme than Tiafoe’s happier results. In the same span, Hubi has outperformed in best-of-three, winning 63% of those matches instead of 58.5%. He is the anti-Berrettini.

We’ve learned today that outlying best-of-five records are probably not predictive of future results. For a statistician, such findings can be a bit disappointing. For Polish fans, though, it’s reason to rejoice. Hurkacz didn’t turn things around in Australia, winning one match and losing his second. Still, a correction remains in the cards. If apparent best-of-five specialists like Berrettini and Tiafoe can lose in the second round, a laggard like Hurkacz could–eventually–give us a deep run.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: