Previous: Trivia Notebook #1

Two more weeks of tennis, another two weeks of trivia. I’ll get to a fraction of it, anyway. In this installment, we’ll look at countries with grand slam match victories, fifth-set momentum, and another sign that the one-handed backhand is dying.

Lebanon and countries with major wins

At the start of the Australian Open fortnight, Hady Habib made history by becoming the first Lebanese player to win a match at a grand slam. I have many questions. How many countries do have wins at majors? The number of countries represented on the women’s side is probably less than the men’s right? And with Lebanon off the board, who’s next?

First off, a clarification: Habib is not the first Lebanese player to win a match at a slam. He’s the first in the Open era. Nadim Hajjar reached the second round at Roland Garros in 1956 before losing to Jozsef Asboth. (For a great Asboth story, see my Roy Emerson essay from the Tennis 128.) That is not to detract from Habib’s accomplishment: He’s the first Lebanese man to appear in a slam draw since 1962.

Let’s focus on the Open era, then. I’m not going to get bogged down in definitions, except to acknowledge that you easily could. No two sources are going to agree on how many countries exist. Conventionally, tennis follows the International Olympic Committee: For example, Puerto Rico is treated as an independent entity, but Scotland is not. There are also plenty of tennis-playing countries with slam victories that have changed their names (e.g. Rhodesia) or ceased to exist (e.g. Yugoslavia). This is all a database-keeper’s nightmare, too. Lebanon has gone through three different IOC codes, and I realized in the course of this research that I’m using different ones for Habib and his countryman Benjamin Hassan. Oops.

Before Lebanon joined the list, 78 present-day countries had scored men’s main-draw slam wins. So Habib makes it 79. Another seven nations appeared in at least one main-draw match but failed to win any.

As I guessed, the numbers are a bit smaller for women. 66 countries have gained a main-draw slam win, and another six have made an appearance. Those figures will soon shift to 67 and 5, respectively, thanks to newly-aligned Armenian Elina Avanesyan. She has gone 0-2 in her first two majors sporting her current flag, but it’s just a matter of time until the top-50 player gets back in the major win column.

Aside from Avanesyan, who’s on deck?

Here are the top-ranked men who would be the first from their countries to win a slam main-draw match:

Rank Player Country 171 Coleman Wong Hong Kong 250 Abedallah Shelbayh Jordan 332 Hazem Naw Syria 336 Eliakim Coulibaly Ivory Coast 619 Nam Hoang Ly Vietnam 623 Mitsuki Wei Kang Leong Malaysia 694 Samir Hamza Reguig Algeria 731 Colin Sinclair Northern Mariana Islands 852 Jesse Flores Costa Rica 887 Seydina Andre Senegal 932 Petar Jovanovic Montenegro

Wong is only 20 years old, so he’s on track to add Hong Kong to the Open-era list. (The city-state tallied three victories in the amateur era.) Shelbayh is only seven months older, so he’s in a good spot as well. The others are considerably more speculative.

The women’s list is deeper. The eleven men listed above are the only ones in the ATP top 1000 from a country without a slam match win. There are 23 women who meet the same standard on the WTA table. Here are the first 13 of them:

Rank Player Country 136 Alexandra Eala Philippines 151 Victoria Jimenez Kasintseva Andorra 160 Kathinka von Deichmann Liechtenstein 201 Raluka Serban Cyprus 251 Justina Mikulskyte Lithuania 281 Lina Gjorcheska Macedonia 341 Sada Nahimana Burundi 404 Malene Helgo Norway 433 Francesca Curmi Malta 492 Klaudija Bubelyte Lithuania 552 Noelia Zeballos Bolivia 620 Aya El Aouni Morocco 678 Angella Okutoyi Kenya 687 Patricija Paukstyte Lithuania

Eala and VJK, both still teenagers, seem like all-but-sure bets. Von Deichmann has been knocking at the door for years. Lithuania has three representatives on this list, so it’s probably just matter of time–though probably more time than it will take Eala or VJK.

Fifth-set momentum

This one is from Eric J via email:

Inspired by Learner Tien’s 5-set win over Medvedev (and his post-match interview in which he confessed to giving up on the fourth set so he could get a bathroom break): Is there a discernible trend in matches that last 5 sets as to whether the player who wins the fourth set when down 2-1 is more likely to win the fifth than his opponent?

Yes, there is. There are three ways to go down 2-1 in sets: lose the first two (LLW), lose the first and third (LWL), or lose the second and third (WLL). At majors in the Open era, for all of those permutations, players who come back to win the fourth have a better-than-neutral chance and taking the match:

Sequence Win-Loss Win% LWLW 522-395 56.9% WLLW 541-455 54.3% LLWW 637-490 56.5% Total 1700-1340 55.9%

The edge has gotten a bit smaller in recent years. Here are the same numbers for slams since 2000:

Sequence Win-Loss Win% LWLW 142-105 57.5% WLLW 168-144 53.8% LLWW 182-158 53.5% Total 492-407 54.7%

Not a big difference, and I don’t want to read too much into it. But I’m still surprised the shift is in that direction. Tanking–usually to save energy, not to race for a toilet break–used to be more common, even standard advice. If the effect is real, it might be that players are generally more fit than they used to be. A half-century ago, a player who lost the fourth set might be gassed, with little hope of recovery. That’s less often the case now.

Either way, there’s a small momentum edge for the fourth-set winner. It’s possible that controlling for matchups would change the results–perhaps stronger players are more likely to be the ones who come back from a slow start to force a fifth set.

One one-hander

Only a few men remain on tour with one-handed backhands, and they combined for a bad fortnight. Stefanos Tsitsipas and Giovanni Mpetshi Perricard lost in the first round. Grigor Dimitrov was forced to retire. That left Lorenzo Musetti:

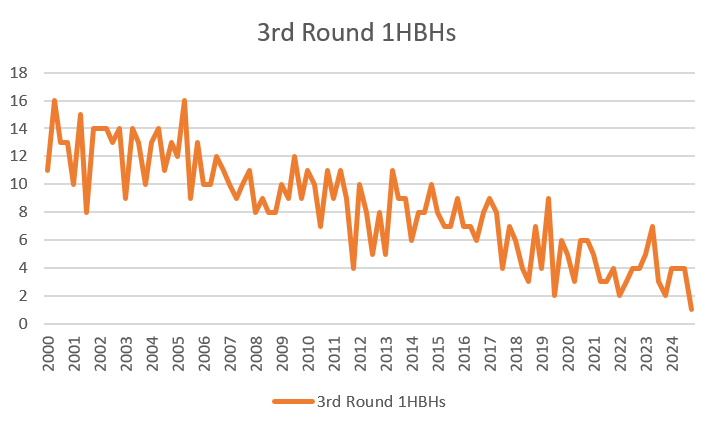

The decline has been remarkably steady. I have backhand types for all 3rd-round players at slams back to 2000. In that time, we’ve gone from one-handed backhands for a full half (16 of 32) of third-rounders at Roland Garros in 2000 and 2002, down to one in Melbourne this year.

This graph shows the number of one-handers in the third round at each of the last 100 majors:

This year’s Aussie is indeed the first major with just one one-hander in the third round. We’ve been getting close for years, with two at Wimbledon in 2019 (Federer and Dan Evans), at Roland Garros in 2022 (Dimitrov and Tsitsipas), and at last year’s Australian (again, Dimitrov and Tsitsipas).

Oddly enough, things swung all the way back up to seven at Wimbledon in 2023, with the surprise runs of Christopher Eubanks and Christopher O’Connell, alongside stalwarts Dimitrov, Musetti, Shapovalov, Tsitsipas, and Stan Wawrinka.

Musetti lost his third-round match to Ben Shelton, so the round of 16 was a two-hander-only club. At least that’s not a first: The same thing happened at the US Open in both 2022 and 2023.

That’ll do it for today. Keep the suggestions coming, and we’ll do some more trivia in a few weeks.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: