Also today: Talking Tennis interview

It wasn’t long ago that Sebastian Korda was considered one of the best prospects in the men’s game. He won a tour level title before his 21st birthday, then fell one match short at the 2021 NextGen Finals. He reached two more finals in 2022, then began 2023 with a near-miss, a momentous three-hour clash with Novak Djokovic in Adelaide that ultimately went to the veteran.

That result, plus a quarter-final run in Melbourne and another runner-up finish last October in Astana, nudged Korda up to a career-high ranking of 23. While he has since dropped the points from Down Under and fallen out of the top 30, my Elo ratings keep him in the top 25, just ahead of the man who defeated him in Kazakhstan, Adrian Mannarino.

This all represents a step forward for the American, especially since he struggled throughout last year with a wrist injury. Compared to expectations, though, it’s a bit underwhelming. Korda’s father, Petr, is a grand slam champion; Sebastian has said he’d like to surpass him and win two. At age 23, he has plenty of time to develop, but eight of the men ahead of him in the rankings–including three of the ATP’s top seven–are younger still. For all the veteran exploits we’ve seen in the last decade of the ATP tour, superstars tend to make themselves known at an early age.

Last night, Korda recorded his 100th tour-level victory, a milestone that reminds us how much he has accomplished in his budding career. The match itself, however, pointed at some of his limitations. The American edged out big-serving French qualifier Hugo Grenier in the Marseille first round, 6-3, 2-6, 7-6(3). The player Korda aims to be would have progressed with ease. As it happened, he won 89 points to his opponent’s 92, marred by an error-spattered string in which he lost seven straight games. Grenier played well, but he is ranked outside the top 150. Korda didn’t look much better.

What’s missing? The 23-year-old has all the tools to climb higher: a six-foot, five-inch frame; an overpowering serve including a hard slice delivery that looks as if it were inherited directly from his left-handed father; a flexible, assured backhand; and a willingness to step into the court to take control of points. To watch him play, there’s very little separating Korda from, say, Taylor Fritz, yet Fritz is a top-tenner. Is it just a matter of time until Korda closes the gap, or does his game need to change?

Progress report

Let’s start with the positive: Korda’s serve is getting the job done. Yesterday, more than one-third of his serves didn’t come back. That’s in line with the average of the several other charted matches from the last 52 weeks. Only a handful of men end the point so often with their first shot; Fritz and Ben Shelton top 30% but still trail Korda. In a losing effort against Hubert Hurkacz in Shanghai last fall, more than 45% of the American’s serves were unreturned.

Those numbers represent a major step forward. Facing Hurkacz at the Australian Open last year, fewer than one-quarter of his serves ended the point. Korda finished below the 25% mark in matches against Daniil Medvedev and Karen Khachanov at the same event, too. It’s ironic that he won that one against Hurkacz and lost in Shanghai, but there’s no counter-intuitive moral to glean: Unreturned serves are an incontrovertible good.

The 23-year-old’s results are less reliable when the ball comes back. Even when presented with an attackable return, Korda sometimes hesitates. In two matches against Hurkacz last fall, Korda didn’t hit a single plus-one winner or forced error behind the second serve. (The high rate of unreturned serves means that his best deliveries aren’t coming back as sitters, but that hardly means that the remaining returns are all so daunting.) Grenier put 21 second serves back in play yesterday, only one of which the American ended with his second shot. Despite the qualifier’s overt aggression–he occasionally swung wildly for winners against Korda’s seconds–the average point on Korda’s deal ran to 4.3 strokes, an unusually high figure for such a strong server.

Taking first and second serves together, how much does Korda sacrifice with his conservative-seeming mindset on plus-ones? I calculated the percent of 3rd shots (plus-ones) and 5th shots that went for winners or forced errors across all charted matches since 2020. Here are results for Sebi, plus those of a few comparable players and the tour average:

Player 3rd W% 5th W% Hubert Hurkacz 19.0% 20.0% Stefanos Tsitsipas 18.5% 20.1% Taylor Fritz 18.2% 17.1% Sebastian Korda 17.1% 16.9% -- Average -- 17.1% 17.3% Felix Auger-Aliassime 16.8% 17.1%

Korda is just not as aggressive as the more successful of his tall, big-serving peers. He out-winners Felix Auger-Aliassime, but I would argue (and will do so at length, one of these days) that the Canadian’s approach is holding him back, as well. It isn’t that Korda is entirely passive on the plus-one, but given the relatively weak return quality he faces, he should be putting away more than a tour-average rate of second shots.

There is, however, a reason for his unwillingness to swing bigger, and that’s where we’ll turn next.

Something wild

Here’s the same table with two more columns: one for each player’s unforced error rate on the 3rd shot of the point, and another for the unforced error rate on the 5th shot:

Player 3rd W% 3rd UFE% 5th W% 5th UFE% Hubert Hurkacz 19.0% 12.8% 20.0% 11.8% Stefanos Tsitsipas 18.5% 11.4% 20.1% 10.2% Taylor Fritz 18.2% 11.1% 17.1% 8.8% Sebastian Korda 17.1% 13.8% 16.9% 12.3% -- Average -- 17.1% 10.8% 17.3% 10.4% Felix Auger-Aliassime 16.8% 10.9% 17.1% 11.6%

Yikes! Korda is wilder on these shots than the other players, so much so that he ends more points with the plus-one shot than everyone on this list except for Hurkacz. Of players with some degree of tour-level success, only Marin Cilic misses more plus-ones. Denis Shapovalov and Alejandro Davidovich Fokina are roughly equivalent to Korda in this department.

We’ve taken a roundabout path to reach a more general fact about the American’s game: He misses a lot of shots. As a fraction of all groundstrokes, Korda ends points in his favor about 10% more often than the average ATPer. But he commits 20% more unforced errors. His plus-ones are of a piece with his entire ground game, even if they’re a bit wilder. Racking up so many unforced errors without a correspondingly large winner count means, by definition, that his baseline game is a liability. Only that big pile of unreturnable serves is keeping him above water.

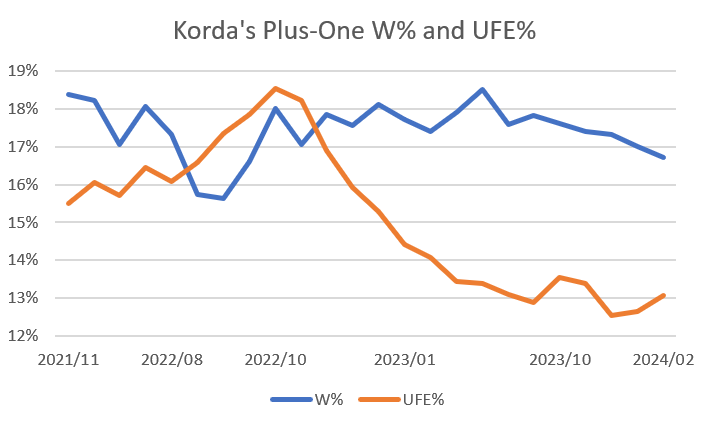

Fortunately, Korda is still young, and his game is not set in stone. He missed 13% of his plus-ones yesterday, but that number is trending in the right direction. Here are his winner and unforced error rates on the third shot of the rally, as ten-match rolling averages going back to the 2021 NextGen Finals:

You don’t need a tour guide to spot the good news here. Korda’s plus-one error rate used to be outrageously high. It’s still higher than he like it to be, but it’s dramatically better, and getting it under control hasn’t cost him much on the other side of the ledger. As he puts the wrist injury fully behind him, there may be even more room for improvement.

The ceiling

I’ve focused on the serve–and Korda’s approach behind it–because that’s the side of his game that will determine how high he climbs. In his career at tour level, he has won 38% of return points, a figure that means he’ll break often enough to win matches when he serves well. Maintaining a 38% rate will get tougher as the quality of his opposition rises, but that may not be a problem: He has already excelled against top tier competition. As Alex Gruskin points out, he’s 18-21 against top-20 players, a record that indicates he’s already able to compete at that level, even if his results against the rest of the pack (and his health) aren’t consistent enough to support a corresponding ranking.

Korda may improve his return game, but if he is to crack the top ten and have a real shot at those two major titles, his serve will make the difference. In the last 52 weeks, he has won 66% of serve points and held 83% of service games, numbers that place him among the top half of the top 50… but not much higher. The serve itself needs no improvement, as we’ve seen. The difference between Korda and someone like Fritz or Tsitsipas is what happens when the serve comes back. The 23-year-old is making progress, but he has more steps to take before he can reach the enormous potential that once seemed so assured.

* * *

Talking Tennis interview

I recently spoke with John Silk of Talking Tennis, and in a one-hour interview ,we covered all things Tennis Abstract: how to get the most out of the site, Elo ratings, common beliefs about tennis stats, and the Tennis 128. Watch it here:

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: