There are a lot of things we could talk about after Jannik Sinner’s latest display of dominance. With a second Australian Open title, his exceptional span of hard court performance has stretched to 13 months, and according to my Elo ratings, only eight players in the Open era have ever been better than the Italian is right now.

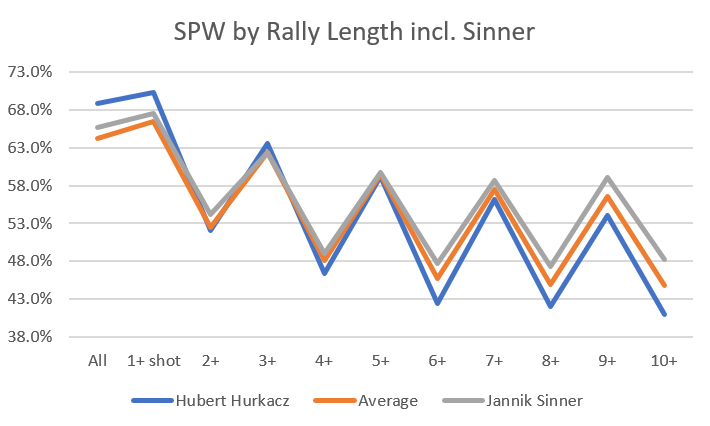

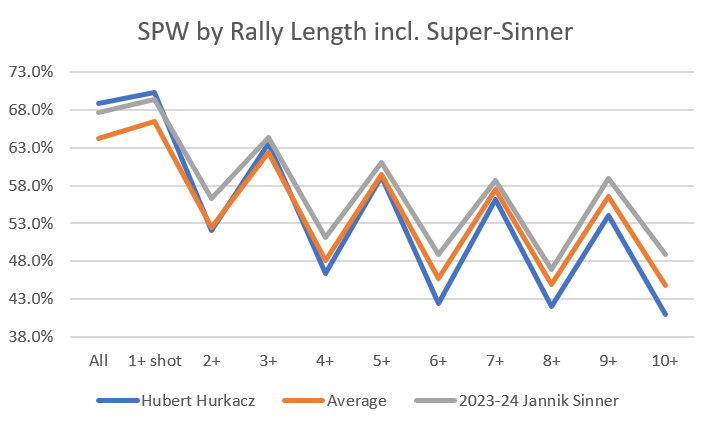

A year ago, I wrote that Yes, Jannik Sinner Is This Good. If anything, he has improved since then. He holds serve more often than anyone on tour–yes, even more than Giovanni Mpetshi Perricard. Yet he is far from one-dimensional. He couples the serve with elite groundstrokes on both wings. He breaks serve more often than all but six players on the circuit.

One particular aspect of Sunday’s victory stands out. In three sets, spanning 15 service games, Sinner did not face a single break point.

Zero break points faced is one of those stats that sounds really good–then it gets even better the closer you look. Alexander Zverev a top-ten returner. He breaks nearly one-quarter of his opponents’ service games. He earns approximately 0.6 break points per game, or three per set. In three sets, the Italian didn’t allow him one.

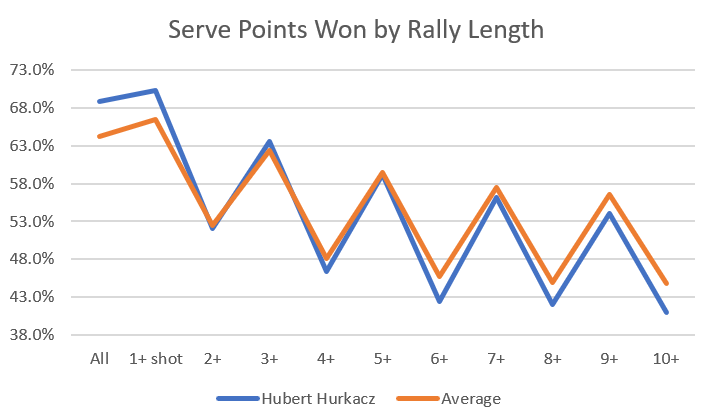

Every season there are a couple hundred matches in which the winner doesn’t face a break point. Yet most of those are short best-of-threes, many of them involving overmatched wild cards and qualifiers. In 2024, there were only five matches in which a top-ten player failed to generate a single break point over more than ten return games. Twice the victim was Hubert Hurkacz, probably the weakest returner among the elites. Another hapless outing came from Casper Ruud, who was held to zero by Zverev at the Tour Finals.

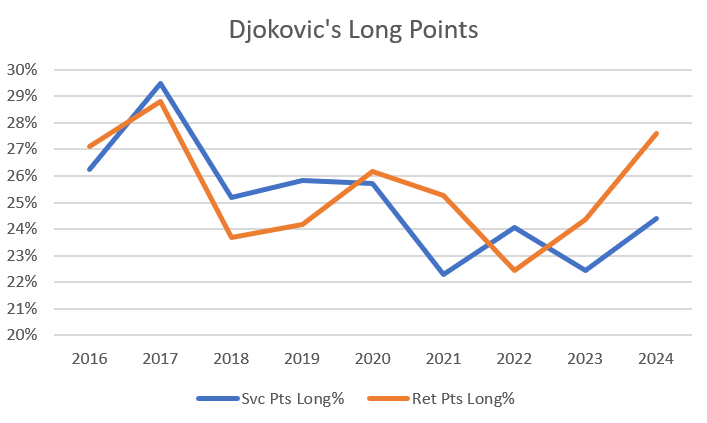

The other two standout matches belong to Sinner. In last year’s Australian Open semi-final, then again in the Shanghai title match, he shut down Novak Djokovic. The only recent precedents for Sinner’s plastering of Zverev are the Italian’s own performances.

What can we learn from the latest episode of the Sinner show?

Situational awareness

Twelve months ago, Sinner was developing a reputation as an escape artist. He beat Daniil Medvedev in a five-set Melbourne final, winning just one more point than the Russian. He snuck past Djokovic twice in November 2023, once winning exactly the same number of points, a second time despite winning four points fewer.

Sinner had a knack for erasing break points. Most players are less successful facing break point than on other service points, because stronger returners generate more break points. (Also, break points tend to crop up amid rough patches, at least for players human enough to occasionally slump.) The Italian, though, saved break points at a better clip than his other service points. He hit bigger at those moments, and it worked.

Recognizing that trend a year ago, I tempered the celebration with a dose of reality:

…I can tell you what usually happens after a season of break-point overperformance: It doesn’t last. Taking over 2,600 player-seasons since 1991, 582 (21.7%) of players saved more break points than they won serve points overall. 183 (6.8%) matched Sinner’s mark of saving at least two percentage points more than their serve-points-won rate.

That sound you hear? That’s Darren Cahill laughing at us. Sinner didn’t quite continue at the same pace, but he still serves better facing break point than otherwise. He wins a tour-leading 71.5% of serve points overall, and the number climbs to 72.5% when an opponent has him on the ropes.

(71.5% is circuit-best, but 72.5% is not: Ben Shelton stands at 73.1%. No one told Jannik, though. In their semi-final, Sinner won 6 of 13 break points against the Shelton serve.)

Of course, this specific skill didn’t come into play on Sunday. Sinner didn’t have break-point-faced results, because he didn’t face any break points. If you have an even bigger weapon to deploy at key moments, why wait until it’s absolutely necessary?

Beyond the escape room

Some players–especially left-handers–are more effective serving to the ad court than the deuce court. That helps them save break points, because most break points (30-40 and ad-out) take place in the ad court.

Sinner is right-handed. Across the 250-plus matches for which I have sequential point-by-point data, he is slightly more effective serving to the deuce court:

COURT A% SPW% Deuce 7.6% 66.6% Ad 6.5% 66.3%

The different in points won isn’t anything to build a strategy around, but the ace-rate gap suggests there might be a meaningful difference.

In Melbourne, the success rates took on a new look. Based on the five Australian Open matches in the Match Charting Project database, here are the same metrics:

COURT A% SPW% Deuce 8.9% 74.6% Ad 9.4% 70.8%

The ace rates flipped, but holy four percentage points! 70.8% serve points won is very good, better than anyone else on tour over the last 52 weeks. 74.6%, though: That’s from another planet. It’s better than John Isner’s best season.

It may be a fluke. After all, it’s just five matches, and Sinner’s deuce- and ad-court results were nearly identical in 2024. But I suspect there’s strategy at work here.

Up to eleven

I noted last year that Sinner served bigger facing break point than he did otherwise: 125 miles per hour compared to 122. What about other key situations?

At the US Open last year, the Italian showed some deuce-court preference, winning 72.7% of deuce-court points compared to 71.3% on the ad side. It wasn’t a matter of power, as he averaged almost identical speeds (117.9 to 117.7 mph) in the two directions.

Speed differences turn up at a more granular level. Here are Sinner’s first-serve speeds at the most common point scores he faced:

Score MPH 15-30 121.0 40-40 120.3 40-15 120.0 0-15 119.7 30-30 119.4 40-30 118.0 30-15 117.7 30-0 117.0 15-0 116.6 0-0 116.6 15-15 115.8 40-0 113.0

(Yes, I know it’d be nice to have 30-40, 40-AD, 15-40, and so on. But this is Sinner we’re talking about. He didn’t face many of those.)

With the exception of 40-15, this list is an awfully good approximation of point scores listed by importance. With more at stake, the Italian hit harder. There’s no apparent trade-off, either. He made more first serves than average at 15-30 and deuce, even with the faster strikes.

The point is that when Sinner feels the need to go big, he has the ability to do so. Most players don’t: Their results don’t get better in critical moments, either because they’re already maxing out their skills on routine points, or because their opponents can raise their levels, as well. But the Australian Open champ has more in the tank than anybody who dares to stand across the net from him.

As the Italian rose through the rankings, he saved that extra oomph for break point. Now that he enters every match as the favorite, he can be even more aggressive. By serving harder at 15-30, or 30-all, Sinner probably doesn’t risk overexposure. With the possible exception of Alcaraz or a time-traveling Djokovic, no one can do much with an accelerated Sinner first serve–even if they’ve seen one recently.

The full arsenal

Put all of this together, and it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that Sinner will continue to climb the all-time list. In terms of peak level, Andy Murray is next:

Rank Player Peak Elo 1 Bjorn Borg 2473 2 Novak Djokovic 2470 3 John McEnroe 2442 4 Ivan Lendl 2402 5 Roger Federer 2382 6 Rafael Nadal 2370 7 Jimmy Connors 2364 8 Andy Murray 2347 9 Jannik Sinner 2325 10 Boris Becker 2320

Sinner wins more service points than anyone else in the game–even when he isn’t particularly trying. At the same time, he is an elite returner.

We’ve seen a few players with a similar service profile. Pete Sampras also had a knack for coming through at the end of sets. But he leaned on his tiebreak skill more than Sinner ever will, because his return game was mediocre. Roger Federer was better: a dominant–and clutch–server, and a more competitive returner than Pistol Pete. Nick Kyrgios had one of the most electric serves in the game’s history, coupled with the ability to focus at critical moments. Yet he was the most one-dimensional of the bunch. His return would have held him back even if he had stayed healthy.

Sinner has all the serve dominance without the drawbacks. He has no apparent weakness. He won’t win all the time, and he won’t stay on top forever, but at the moment, it’s hard to see how anyone will stop him.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: