2024 was a good year for exhibition tennis. The Saudi-banked Six Kings Slam set a new standard for prize money. Rafael Nadal and Carlos Alcaraz took the long tradition of Las Vegas tennis challenges to Netflix. The Ultimate Tennis Showdown made three glitzy stops. Novak Djokovic helped Argentina celebrate Juan Martin del Potro. Even Scandinavia got involved, with a home-and-home duel showcasing Casper Ruud and Holger Rune.

The tennis season is long. Put enough money on the table, though, and it can always get longer.

Exhibitions tend to highlight the gaps between the game’s haves and have-nots. Even the official tours are headed in that direction. The ATP and WTA aim to trim the number of small events to better focus attention on longer, 1000-level tournaments. Rumors persist of a Premier League-style “super tour” that would go even further.

It’s a delicate balance. You can’t hold exhibitions without bona fide stars. You can’t have stars without universally recognized events like Wimbledon. And you can’t have Wimbledon without a thriving ecosystem of tournaments that both identify contenders and allow future champions to develop. The Six Kings Slam was about as far as you could possibly get from an ATP 250 in Santiago, but one relies–however indirectly–on the other.

These tensions are not new. There has always been a scarcity of megastars whose celebrity transcended a couple dozen standard tour stops. Though the ultra-bankable Big Four is fading into history, other trends–exemplified by Saudi money and Netflix-style starmaking–will continue to raise the incentives for exhibition-style tennis. It’s too early to tell whether things will get better or worse, but they’ll almost certainly get different.

How did we get here?

For nearly as long as there have been tennis champions, there have been promoters trying to put them in front of more fans for more money. In 1926, Suzanne Lenglen, the greatest woman player up to that time, became the first superstar to go pro. Her 40-stop series was more like a modern concert tour than anything in the tennis world. She made $100,000 for three months’ work, the equivalent of nearly $2 million today.

Lenglen soon hung up her racket, but the template had been proven. For the final four decades of the amateur era, a rotating cast of standout players from Bill Tilden to Rod Laver slogged through grueling barnstorming tours. Apart from occasional appearances in New York, London, and Australia, it wasn’t glamorous. But it was a more reliable living than taking under-the-table “expense money” from organizers of amateur events.

It didn’t take long before the business model became clear. A pro tour could support four athletes: Two big names (preferably rivals), plus two more who could play a warm-up match, then later join their colleagues for doubles. The tour did best when one of the headliners was a recent Wimbledon champion. It wasn’t unusual for the newly-minted titlist at the All-England Club to sign a contract within days of collecting his trophy.

Attempts to broaden the base of professional tennis usually failed–or, at least, didn’t become any more than another quickie tour stop. To fill out a proper tournament field, promoters had to invite retired champions and teaching pros. The would-be pro “majors” had an appeal not unlike a senior tour event, giving fans a chance to see, say, Don Budge far past his prime.

Amateur officials, as you might expect, detested this state of affairs. Wimbledon was turned into a glorified qualifying tournament, the winner to receive a six-figure check to never appear at SW19 again. While they could have stopped the exodus by offering prize money, it’s easy to sympathize. The pro tour was a parasite, trading on the fame of stars it did nothing to create.

Won’t get fooled again

The Open era kicked off in 1968, quickly consigning amateur tournaments to also-ran status. A few players began to get rich, and it was possible to make a living as a second-tier tour regular. Within a decade, though, exhibition tennis threatened the burgeoning pro circuit.

The tennis boom of the 1970s created vast numbers of fans, and with the help of television, the era’s stars became more famous than ever before. The 1973 Battle of the Sexes was not just a turning point for women in sport. It proved the potential of a one-off spectacle. Why bother with a whole tournament when you could pit Jimmy Connors against Rod Laver at Caesar’s Palace?

In the early 70s, there wasn’t much tension between the tours and exhibitions, because the unified tours didn’t exist. A national federation might gripe about a big name skipping a circuit stop in favor of a bigger payday elsewhere, but federations were losing their grip on the sport. There was little they could do about it.

Soon, though, battle lines formed. World Team Tennis muscled their way onto the stage in 1974, offering players guaranteed contracts to play up to 60 dates from May to September. WTT was expansive enough to accommodate lesser names alongside the box office draws, but the very nature of the league made the pecking order clear. Superstars demanded six-figure deals and often forced trades so that they could play for a chosen franchise. WTT could be nearly as grueling as the old pro tours, but it beat the procession of smaller events between Wimbledon and the US Open.

By the end of the decade, the ATP and WTA had organized themselves into circuits that resemble what we have today. Stars like Chris Evert and Bjorn Borg were raking in prize money. The problem was, on the exhibition market, they were worth even more. Borg, in particular, would cash in at any opportunity, sometimes playing dozens of exhibition matches in a single season.

The men’s tour eventually responded by requiring that players enter a minimum number of sanctioned events each year, one factor in Borg’s early retirement at the age of 26. But most players were willing to compromise, entering a couple dozen official tournaments, then jetting from Europe to Japan and back to pad their bank accounts.

The compromise

Six Kings aside, we’re still far from the peak era of exhibition tennis, when Borg and Ivan Lendl played one-nighters for well-heeled fans around the globe. The ATP has steadily tweaked its rules–no exhibitions that clash with bigger tour events, for instance–while upping its own prize money.

The tours have also indirectly limited exhibitions by their own natural growth. One of the biggest exho markets in the 70s and 80s was Japan, where an increasingly rich population wanted a taste of what Westerners could enjoy at home. As the tours gave more prominence to sanctioned tournaments in Tokyo, Osaka, and elsewhere, there was less demand for one-off player appearances.

That, in short(?), is how we got here. Stars are able to play non-tour events, but only sometimes. They hardly need to, since an athlete with any kind of box office value is making seven figures in prize money, not to mention endorsements. Most localities that can support a top-tier event have got one, within the framework of the official tours.

However, it wouldn’t take much to render this equilibrium unstable.

Threat models

The biggest immediate danger to the existing structure of pro tennis is Saudi money. The nation’s Public Investment Fund basically blew up golf, poaching stars for a rival tour and leaving the sport fractured.

Fortunately, tennis officials were able to watch and learn. The Saudis have been welcomed as partners, hosting the WTA Finals and the ATP NextGen Finals, as well as sponsoring both tours’ ranking systems. The Six Kings Slam doesn’t seem like so much of a threat in the context of so much collaboration.

If the Saudis decide to make a bigger move, even that will likely be in partnership with the majors–the so-called “super tour” proposal. The resulting circuit would probably have fewer, higher-paying tournaments. By extension, it would support a smaller group of players. Breaking onto the tour would be more lucrative than ever, but many currently-fringe competitors would be stuck on an expanded version of the Challenger tour.

Maybe a super tour is imminent. I have no idea. It would certainly change the face of the sport, though not beyond recognition.

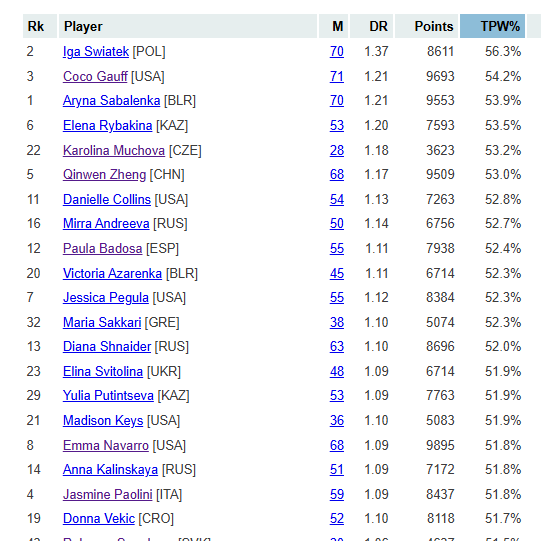

The bigger threat, as I see it, is in the longer term. Sports–not just tennis–have learned to promote their biggest stars, earlier and more persistently than ever before. Think of all the “NextGen” hype tennis fans have been subjected to for more than a decade now, since Grigor Dimitrov was a teenager. Now we’ve entered the “Drive to Survive” era, where every sport wants Netflix to do what it did for Formula 1. To grow the game–the thinking goes–stars need to develop into global icons, thus attracting new fans. Can’t just sit around and wait for the next Federer to manage it himself.

The risk is that by marketing a superstar, the value accrues to the superstar, not the sport. If more people tune into Wimbledon to watch Sinner play Alcaraz, Wimbledon reaps the benefit of the ratings and sponsorships. Yes, Sinner and Alcaraz get paid well, too, and maybe prize money goes up next year. But at what point does Wimbledon have less status than the stars themselves? When Alcaraz has his own Netflix doc and Sinner is the most popular man in Italy, who cares about the strawberries and cream?

Put another way: Imagine that the Saudis were looking to elbow their way into sport in 2008. After the epic Federer-Nadal Wimbledon final, they offered both men a ten-year, billion-dollar contract to tour the globe (with frequent stops in the Gulf), playing head to head in one sold-out arena after another. Is the offer so implausible? Are we sure that Roger and Rafa wouldn’t have taken it?

Sinner and Alcaraz are hardly Federer and Nadal–at least not yet. But their agents, and the tour’s marketing team, and a film studio or three, are trying very hard to raise them to that status. If it isn’t Sinner and Alcaraz, it’s the next generation of superstars after that. Eventually, someone, or some small group of players, will be big enough that they can sell a two-man product. Team sports don’t have to worry about that; even golf would have a hard time selling much match play. But tennis has sold two-player rivalries for a century.

That, to me, is the logical extension of exhibition tennis, the worst-case scenario that guts the sport as we know it.

Events like the Six Kings Slam, Laver Cup, and UTS are fine when there is a deep, thriving tennis ecosystem for 45 weeks a year. (I’d even settle for 35!) We are quite far, I think, from the point where the number of exhibitions threatens the tour itself. But we are closer to the more dangerous point where a small group of superstars don’t need the tour at all. Any athletes who ultimately cash in their celebrity to go it alone will do very well in the deal. But the rest of us will be left with a much less compelling sport.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: