A few weeks ago, Agustin Lebron made a broad claim:

Most strategic improvements in sports have been in the direction of increasing variance and living with the (better EV) results:

Baseball: more extra base hits, no more bunting.

Football: more passing game, going for it on 4th.

Golf: driver ball speed increases.

Bball: 3 pointer

Tennis: bigger serves/groundstrokes.

Snooker: cannoning the pack to extend breaks.

Chess: sub-optimal but niche exploitive lines.

“EV” means expected value or, roughly speaking, probability of success. Thanks to baseball’s sabermetric revolution and its influence on other sports, we better understand how players and teams win. Competitors, knowingly or not, are chasing EV.

Lebron’s claim is a bit more specific, that players and coaches across sports are playing riskier games because the ultimate payoff is greater. In baseball, a sacrifice bunt makes it more likely that a team scores one run, but less likely that the team piles on multiple runs. Hoopsters land two-point shots at a better rate than three-pointers, but the additional point makes the tradeoff worthwhile. Ice hockey coaches pull the goalie sooner than they used to, taking the chance that an extra skater will result in a game-tying goal, even if the decision could result in an easy score for the opposition.

Many more examples and counter-examples appear in the discussion around Lebron’s tweet and in the comments at Marginal Revolution.

It’s less clear that tennis ought to be grouped with these other sports. It may be true that players have uniformly bigger serves, or that they hit forehands harder than their predecessors. But is their pursuit of expected value causing them to take more risks?

Serve trends

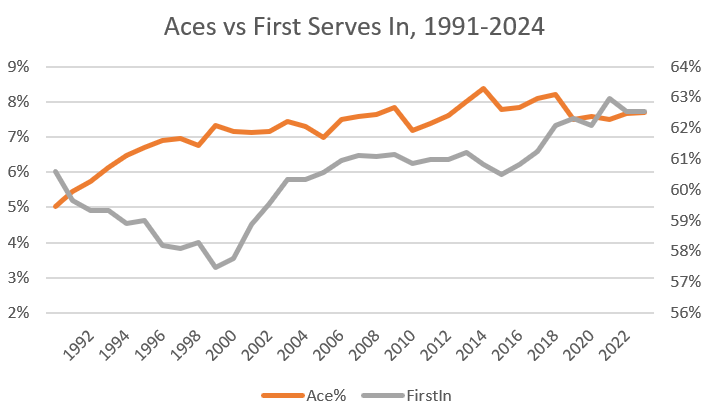

Since 1991, when the ATP started recording stats like aces and double faults, aces have indeed gone up. That first year, about 5% of points ended with an untouched serve. The tour reached 7% by 2000, then cleared 8% in 2014. The rate has held fairly steady since then, sitting at 7.7% in 2024.

One way to hit more aces is to push closer to the edge. Aim for the lines, smack it as hard as you can, and accept that you’ll miss more, too. That would fit nicely with the increasing-variance hypothesis. But that’s not what has happened. As aces have gone up, the percent of first serves made has also risen:

The increasing-variance hypothesis holds for 1991-2000: Aces went up at the cost of fewer first serves in the box. Since then, though, players have kept hitting more aces (if only slightly), while landing even more first serves.

This is almost definitely thanks to better racket and string technology. You can swing harder than ever, with more spin than ever, and keep control of the ball. But that isn’t the whole story. For any given level of technology, players could take more risks, cracking still more aces at the expense of fewer first serves in. For nearly a quarter-century, that is not the decision pro men have made.

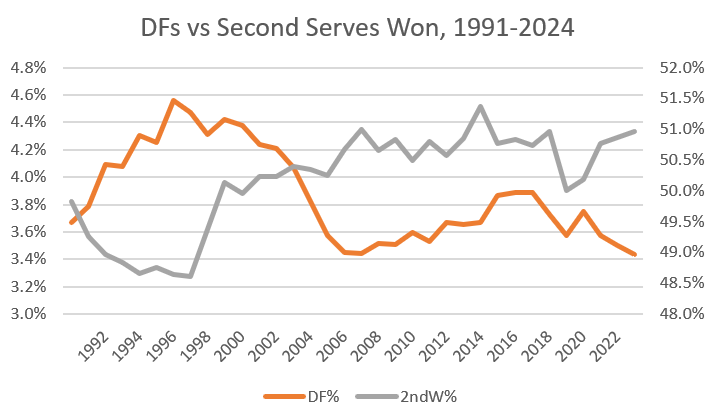

Second serves and double faults tell the same story:

Second serves offer an opportunity to take even more risks. If you go big and miss, you lose the point. But men have generally opted to take their chances with a ball in play. Double faults have cratered since the mid-90s and are currently at an all-time low. Yet players are winning about as many second serve points as ever.

In the last decade, we’ve seen a few players–Nick Kyrgios and Alexander Bublik come to mind–who do sometimes take their chances with a big second serve. Across 129 charted matches, Kyrgios hits aces on 4% of his second serves. Tour average is below 1%. Even Nick, though, doesn’t think it’s worth a major change in his risk profile. His career double fault rate is 4.2%: above average, but hardly an outlier among tour regulars.

The Aussie recognizes that the second serve evolved for a reason. Hitting a big second serve–deploying, in other words, two first serves–is a negative-EV play. It may be worth trotting out for variety’s sake, but not more than that.

Which brings us, finally, to Matteo Berrettini. The six-foot, five-inch Italian is the apotheosis of the big-serve, big-forehand, “plus-one” game. He’s the sort of player Lebron might have been thinking of when he bucketed tennis with the other sports on the list.

For all his power from the line, Berrettini is as conservative as they come. His career ace rate of 12.3% is outstanding, yet there is no apparent cost. He makes almost 64% of his first serves. He wins more second serve points than average, too, despite a miniscule double-fault rate of 2.4%. His game has gotten even safer as he reaches his late 20s. This year, he is hitting slightly more aces (12.8%) and landing far more first serves (68.6%) and committing fewer double faults (2.0%).

If the Italian is any indication, tennis is moving toward bigger serves and forehands. Yet when it comes to the serve, variance is headed in the opposite direction.

Rally aggression

What about groundstrokes? Nearly everyone these days talks about plus-one tennis. The serve–when it doesn’t end the point outright–generates opportunities to put the ball away. When those opportunities appear, don’t screw around! The strategy looks different in the hands of Berrettini than it does with, say, Jelena Ostapenko, but more than ever, players think in terms of recognizing and converting opportunities to end points.

Once the serve has landed, some players have indeed adopted a higher-variance approach that is probably unprecedented. Ostapenko, the freest swinger of all, ends nearly two-thirds of points on her own racket. Inevitably, she misses a huge fraction of those. Her Rally Aggression score of 182 (on a scale designed to run from -100 to 100) leads active players, and it massively outstrips anyone who started their career before about 2005.

Here, alas, we are hamstrung by data limitations. I discussed the men’s tour above because women’s ace and double-fault data only goes back to 2010 or so. The situation is even worse with groundstrokes. While the Match Charting Project now spans over 14,000 matches, relatively few of those predate 2010. Those “early” matches are heavily skewed toward a handful of top players.

We can still draw some comparisons. Lindsay Davenport and Maria Sharapova, often-erratic free swingers a generation or two before Ostapenko, grade out with Rally Aggression scores in the mid-40s. That’s below Iga Swiatek. Let that sink in for a moment. Today’s rock-solid, heavy-topspinning queen of clay plays as aggressively as two earlier-era emblems of high-risk slugging.

Again, we see the effect of better tech. When Ostapenko swings away, there is perhaps a 60% chance it lands in. If it does, it probably isn’t coming back. When Davenport (or to a greater extent, her own predecessors) took a big cut with a 60/40 chance of falling between the lines, it wasn’t quite as hard, and it didn’t have as much spin. It was that much less likely to end the point immediately, or in her favor at all. The chance of an error was always high; modern rackets and strings have upped the odds that the risk is worth taking.

Berrettini, though, once again illustrates that the risk isn’t necessary. The Italian’s Rally Aggression score is 24: above average but not by much. In part the number is low because he struggles to create opportunities on return (or when his serve fails to create chances), but in part he rates where he does because he doesn’t often miss. Roger Federer, for broadly similar reasons, is in the same range.

Modern tech allows players to hit as many winners as ever with less risk. Jannik Sinner, with his career Rally Aggression score of -24 and Carlos Alcaraz, at +8, point toward a lower-variance future, at least in the men’s game.

Ebbs and flows, serves and volleys

The biggest gap in the increasing-variance hypothesis is that it doesn’t explain the death of the serve-and-volley.

Few tactics in any sport are higher variance than old-school, rush-the-net-on-every-point serve-and-volleying. Think of Boris Becker at Wimbledon. He hit a bomb, and if it came back, he was often sprawled across the court simply trying to get a racket on the ball. Today’s net forays aren’t always so kinetic, but they remain high-risk. For every easy volley, there’s an untouchable passing-shot winner.

What’s more, the most dedicated form of serve-and-volleying, Jack Kramer’s “Big Game,” was explicitly an EV play, the brainchild of an actual engineer decades before anyone thought to put “sports” and “analytics” in the same sentence. Kramer and club-mate Cliff Roche worked out the angles and the probabilities, and the on-court results were so overwhelmingly positive that other Americans quickly followed suit. Thanks to a Davis Cup drubbing in 1946, Kramer’s game also changed the course of Australian tennis, inspiring Frank Sedgman and indirectly defining the style of innumerable hopefuls, including Rod Laver.

Serve-and-volleying, in the right hands, was the smart play for reasons that no longer persist. Returners couldn’t do much with a good serve. Court conditions made baseline tennis chancy: Much more tennis was played on grass, and almost none of that grass resembled the impeccable grounds at Wimbledon. Rushing the net was the only way to avoid losing on a bad bounce.

There’s a direct line running from Kramer, through Laver and Pete Sampras, to early-career Federer. Roger gave up serve-and-volleying only when Lleyton Hewitt showed how a sturdy, precise defense–made possible, again, by improved tech–could turn even a strong serve-and-volley attack into a negative-EV proposition.

The overarching theme here is that tennis pros will chase expected value, just as they have for a century. If they don’t, other players will come along with a better approach and displace them. The tactics that work in a given era are heavily driven by tech, and they may or may not move in the direction of higher variance.

The women’s game shows us the potential of high-risk tennis. So many top players go for broke that someone like Swiatek–an aggressive player by historical standards–looks conservative by comparison. Ostapenko-style slugging looks nothing like serve-and-volleying, but the philosophy is similar: Put the ball away before your opponent has the chance.

The men’s game, though, is becoming ever more precise. Sinner and Alcaraz don’t have low Rally Aggression scores because they play so passively. They just don’t miss very often. Berrettini is more aggressive, but only just. Few men hit serves harder or pepper the corners so persistently. Fewer still are so relentless in how they capitalize on a short ball. Yet he does that seemingly without cost. The Italian has plenty of limitations–injuries and a limited backhand, for starters–but they aren’t tactical. He and his colleagues have concluded that higher risks aren’t worth it, and they are probably right.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: