On Saturday, Jakub Mensik did it again. Jack Draper was coming off an Indian Wells title, the fortnight of his career, but Mensik was a little bit better. Both sets went to tiebreaks, and twice, at six-all, the 19-year-old Czech took his serving to a new level. He won 14 of 19 tiebreak points and sent the Brit home early.

After such an assured performance, Mensik’s third-rounder felt like a gimme. Roman Safiullin gave him two looks at break points, and that’s all he needed. Behind another monster serve barrage, the Czech waltzed into the fourth round, 6-4, 6-4.

Mensik currently stands outside the top 50, but his ranking doesn’t tell the full story. For one thing, he made his top-50 debut late last year, and his Miami points will almost certainly be enough for him to return. Beyond that, he has proven that he fears no one on tour. Draper was his 6th top-ten win in 11 tries. What’s more, Mensik won a set in three of the five losses, including a meeting in Shanghai last fall with Novak Djokovic.

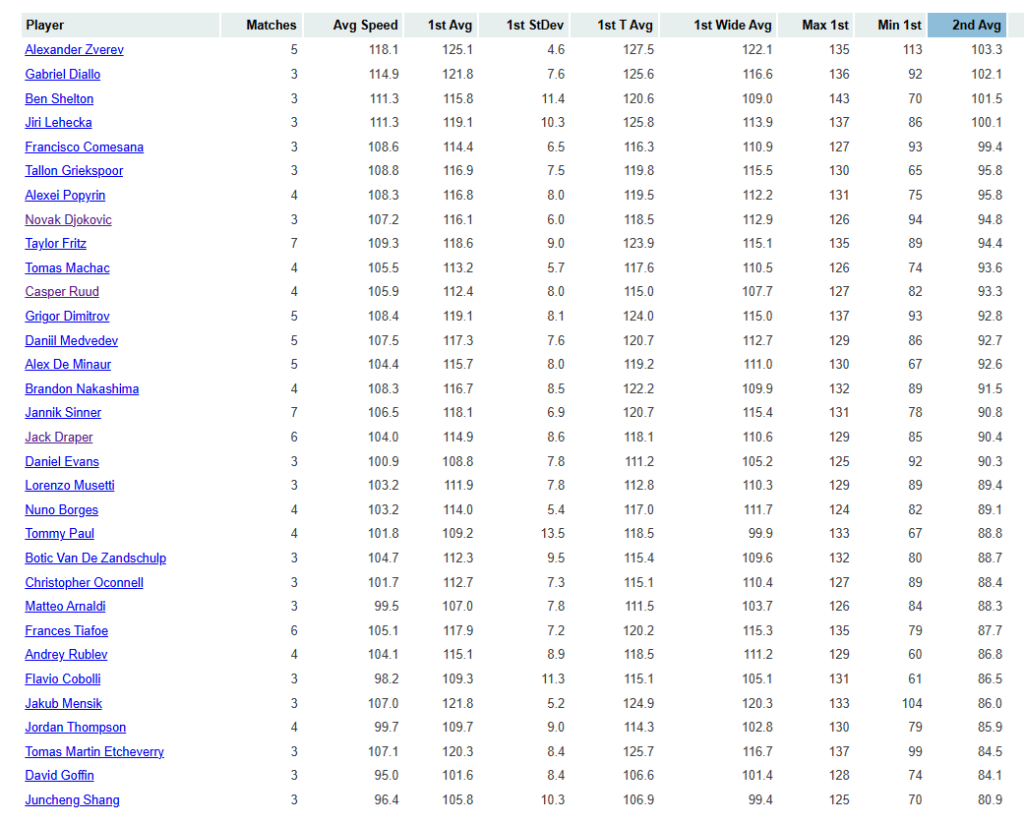

Djokovic called him “one of the best servers we have in the game.” Indeed, since the US Open last year, the six-foot, four-inch Mensik is cracking aces on more than 15% of his serve points. Only Giovanni Mpetshi Perricard and Quentin Halys rate better among tour players. He has taken things to a new level in Miami. In each of his three matches–against Roberto Bautista Agut, Draper, and Safiullin–he has hit an ace on at least 26% of his serve points. That’s Reilly Opelka-level serve dominance, and even Opelka hasn’t posted three straight ace rates like that since 2022.

Mensik is one of the most exciting prospects on tour, yet Joao Fonseca-mania doesn’t leave much attention to anyone else. What do we make of those top-ten wins… and the non-top-ten losses that have kept him on the edge of the top 50? How should we rate the rest his game–you know, those occasions when he doesn’t end the point with a first serve? Let’s dig in.

Proof of concept

Here is the top-ten record:

Pretty good for someone with another five months left in their teens.

Draper wasn’t the first top-tenner that Mensik overpowered. In the six wins, the Czech held serve 90% of the time, winning three-quarters of first serve points. Djokovic and Alex de Minaur figured out how to neutralize the serve, but lesser returners (read: most other humans) have not.

Even before the Miami upset, Mensik was just the 21st player since the beginning of the ATP rankings to win at least five of his first ten meetings with top-tenners. (I’m excluding players who were already established in 1973, when the points table debuted.) He’s just the 12th ever to win six of eleven. Here’s the full list:

Player First 10 First 11 Alberto Mancini 7-3 7-4 Miloslav Mecir 7-3 7-4 Fernando Gonzalez 6-4 7-4 Marc Kevin Goellner 6-4 7-4 Lleyton Hewitt 6-4 6-5 Jakub Mensik 5-5 6-5 Ugo Humbert 5-5 6-5 Marcos Baghdatis 5-5 6-5 Marat Safin 5-5 6-5 Carlos Moya 5-5 6-5 Chris Woodruff 5-5 6-5 Magnus Larsson 5-5 6-5 Boris Becker 5-5 6-5 Fabian Marozsan 5-5 5-6 Aslan Karatsev 5-5 5-6 Matteo Berrettini 5-5 5-6 Reilly Opelka 5-5 5-6 Mardy Fish 5-5 5-6 Nicolas Kiefer 5-5 5-6 Henrik Holm 5-5 5-6 Greg Holmes 5-5 5-6

It’s a strong list, if a bit scattershot. We have all-time greats, plus Aslan Karatsev and Greg Holmes, who apparently upset both Mats Wilander and Jimmy Connors. The playing styles might tilt a bit toward heavy hitting and big serving, but not overwhelmingly so.

I mention playing styles because rocket serves, like Mensik’s, have a way of turning matches into coin flips. If the serves aren’t coming back, it doesn’t matter how well the guy returns. Other skills fall by the wayside: We’re headed for a tiebreak. Apart from a pair of early breaks, that’s what happened in the Draper match. John Isner won three of his first ten top-ten encounters, and Opelka earned a spot on this list.

Everything else

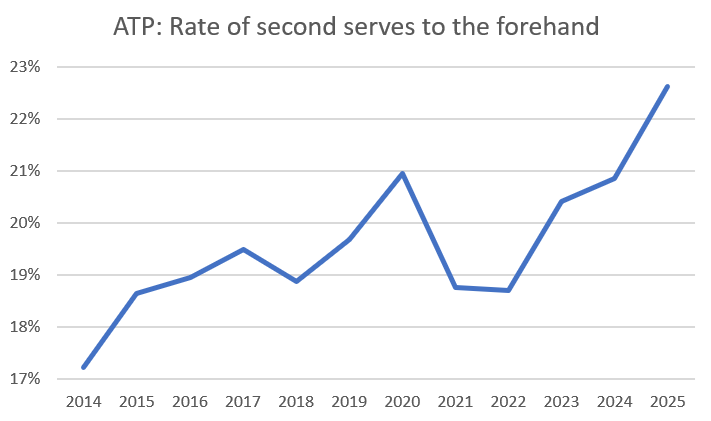

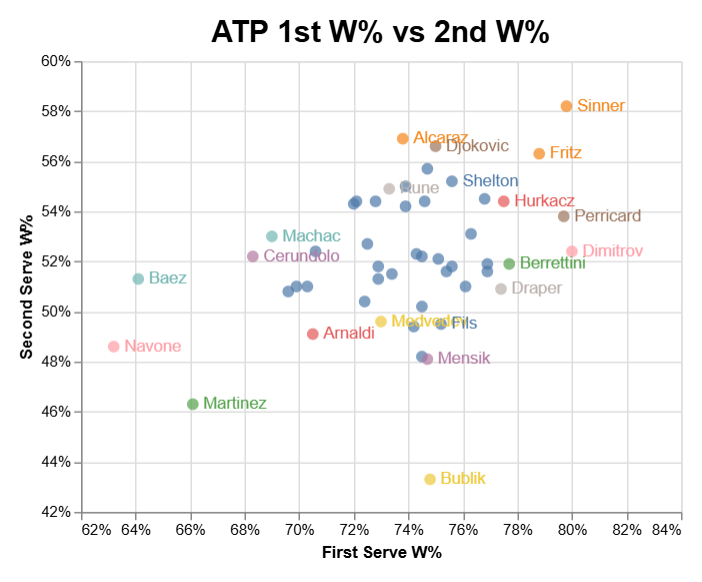

When the serves do come back, though, it’s anybody’s ballgame, top-ten opponent or not. For Mensik, just about everything apart from the first serve is a relative weakness. In the last 52 weeks, he has won just 47.4% of his second-serve points, worse than 49 of the top 50 players. (Pedro Martinez is the one guy with a sub-Mensik number.)

The Czech has gotten accolades for his backhand, but it’s not really a weapon. While it doesn’t hold him back, it rates about tour average by my Backhand Potency (BHP) metric. His Forehand Potency is the real issue. At just +1.1 per 100 forehands, he ranks ahead of only a few of his colleagues, including Opelka, Mpetshi Perricard, and Hubert Hurkacz. Hurakcz has proven that it’s possible to hang around the top of the game without much help from the forehand, but it’s a narrow path to follow.

All this adds up to some painful numbers in rallies. I was going to say “long rallies,” but Mensik starts to see a disadvantage about as soon as the word “rally” comes into play. In eleven charted matches over the last 52 weeks (not counting the Draper upset), here are how his results shake out by rally length:

Length Win% 1-3 shots 52.2% 4-6 shots 45.3% 7-9 shots 41.9% 10+ shots 42.0%

52% on short points is great! That was enough to crack the top ten list when I looked at the same category last week in the context of Draper’s excellence. Since these stats encompass both serve and return, it tells us that he’s cleaning up more of his own quick points than his opponents can manage of their own.

The rest of the story, though, is bleak. He ranks near the bottom in all three of the other categories. If we lump them together, he win the fewest points of anyone with at least ten charted matches in the last year:

Player 1-3 W% 4+ W% Jakub Mensik 52.2% 43.8% Mpetshi Perricard 51.6% 43.8% Zhizhen Zhang 48.5% 44.1% Jiri Lehecka 51.8% 44.2% Ben Shelton 50.5% 44.7% Hubert Hurkacz 55.0% 45.4% Lorenzo Sonego 52.5% 45.5% Tallon Griekspoor 49.8% 46.1% Flavio Cobolli 44.9% 46.6% Alexei Popyrin 50.4% 46.8% … Jack Draper 53.3% 48.8% … Stefanos Tsitsipas 50.5% 50.6% … Alexander Zverev 53.0% 53.1% … Novak Djokovic 53.7% 54.9% Carlos Alcaraz 52.5% 55.8% Jannik Sinner 54.4% 57.0%

Somehow, it gets even worse. With enough short points, weak long-rally skills are survivable. Yet Mensik plays more long points than most of these guys in the bottom ten. The 1-to-3-shot category accounts for less than 63% of his points, while it makes up more than 70% of Mpetshi Perricard’s. Even Jiri Lehecka, hardly an extreme case like GMP, comes in at 66%.

Second to last

Mensik is hardly an elite returner, but he is good enough for now. He has won about 37% of his return points over the last 52 weeks, a rate that–coupled with strong serving–is sufficient to get him into the top ten. Despite his relatively low ranking, he has posted those numbers against high-quality competition. His median opponent has been stronger than those faced by Stefanos Tsitsipas or Casper Ruud.

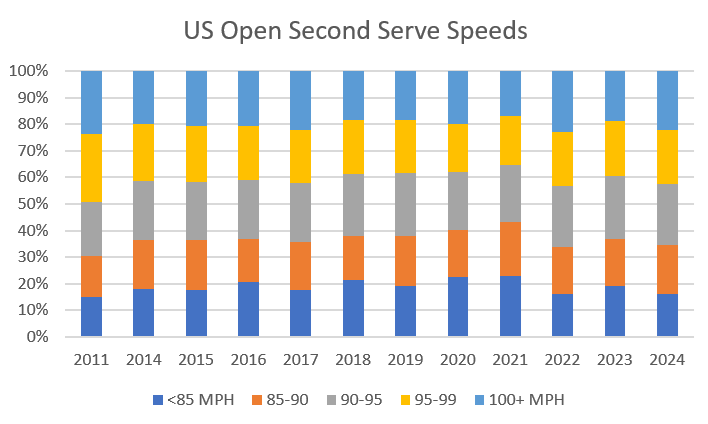

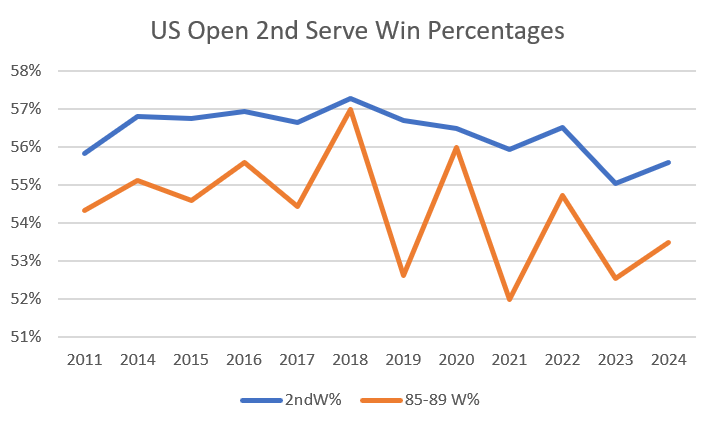

The immediate concern for the Czech is his second serve. I mentioned earlier that he wins barely 47% of those points. Ben Shelton, who wins exactly as many first-serve points as Mensik does, converts 55% of his seconds. While that’s unusually good, nearly every player in the same first-serve territory wins at least 51% behind the second serve.

This is a good time to remember that Mensik is 19. He hasn’t been six-foot-four for long. It’s possible that his second serve will look entirely different in two years than it does today. He’ll certainly hope so. He misses more than 12% of his seconds, a double-fault rate that would be acceptable only if he were taking chances and reaping the rewards of those risks. At the moment, he’s just struggling.

The second-serve weakness is more than enough to flip the outcome of a match. In the last year, when Mensik has landed at least 60% of his first serves, his record is 16-5. Under 60%, it’s 12-17.

The root of the problem is what happens when the second serve comes back. The Czech’s second delivery isn’t yet strong enough to generate many easy plus-one opportunities, and his ground game isn’t sturdy enough to make up for it. When his first serves come back, his results are close to tour average. But when the second serve comes back, he ranks at the very bottom of the table.

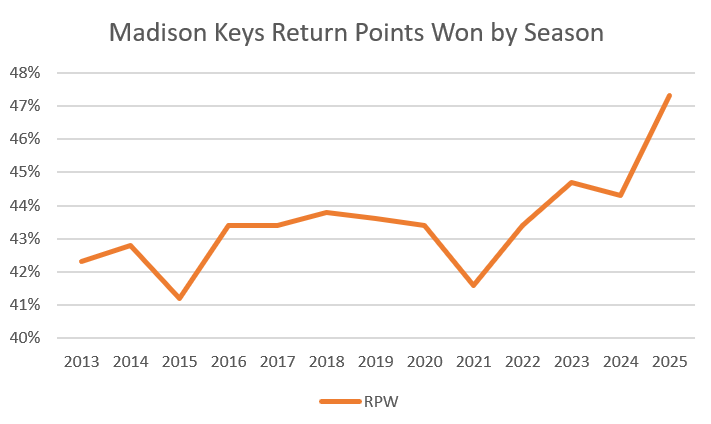

This scatterplot shows every player with at least ten charted matches over the last year. It compares each player’s win rate when their first serves come back with their results when second serves come back. Guys below the dotted line see relatively worse outcomes behind their second serve:

There’s no single limitation that is depressing Mensik’s second-serve results. The positive spin on that is that he has a lot of areas with room to improve. Even an average second serve–seemingly a reasonable goal for a man with such an imposing first–would probably make him a top-20 player.

The way forward

Nothing makes it easier to dream about a big future in tennis than a monster serve. Any list of overrated youngsters is going to be littered with powerful teens who remained too one-dimensional to convert all their aces into tournament victories.

That, I think, is the low-end forecast for Jakub Mensik. If he simply keeps doing what he’s doing, he could be a top-40 or top-50 player for a long time. His first serve is that good, and the rest of his game is adequate. He probably wouldn’t continue to win half of his top-ten meetings, since the game’s top players would have more time to figure him out.

On the other hand, again, he’s 19! The difference between his first- and second-serve results is a statistical oddity, which could mean either that he is uniquely one-dimensional, or that he has plenty of room to develop. The latter seems more likely. He may remain limited on return, but a second serve to match his first would make him near-unbreakable. That’s the recipe for a lot more top-ten wins, and possibly for a single-digit ranking of his own.

* *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: