By November 1973, everyone in the sports world was talking about Chris Evert, the 18-year-old Floridian on the cusp of dominating women’s tennis. For the next couple of years, though, fans hailing the victories of Chris Evert would need to be a little more specific.

On November 14th at Aqueduct Racetrack, a new champion was minted in the Demoiselle Stakes: a two-year-old filly named Chris Evert. Her owner was a Massachusetts clothing manufacturer named Carl Rosen, and Chrissie–the one who swung a racket–endorsed his tennis line. The Wimbledon runner-up and the filly wouldn’t cross paths until the following year, but Evert the tennis player kept tabs on Rosen’s equine protégé.

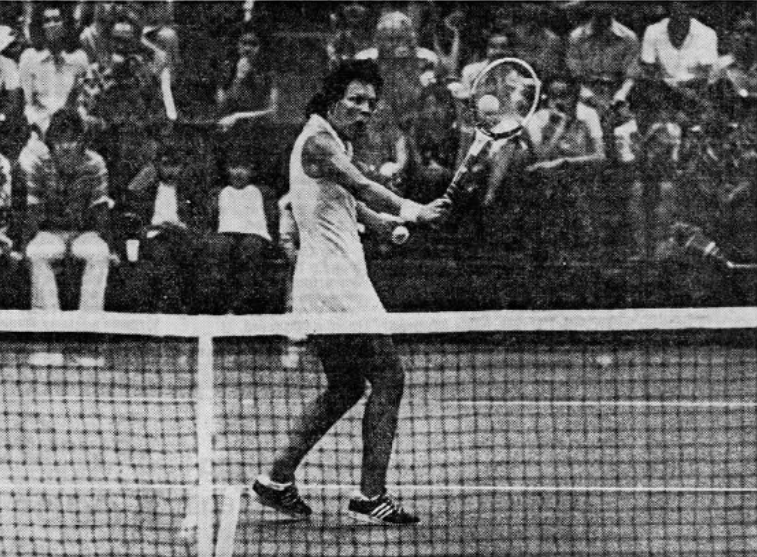

Both Everts would reach new heights in their respective fields in 1974. The Floridian would break through at the majors, winning Roland Garros and Wimbledon in succession. The horse would, if anything, be even more dominant. She won the Filly Triple Crown, the prestigious collection including the Acorn Stakes, the CCA Oaks, and the Alabama Stakes.

The two champions finally came face to face in July 1974 at the Hollywood Park Racetrack, when the tennis player watched her namesake take on Miss Musket in a one-on-one match race. With $350,000 on the line, Chris Evert won by 50 lengths. It was an even more comprehensive victory, and a far richer payday, than Chrissie could’ve managed against Bobby Riggs in the would-be match that–finally–had faded from the headlines.

Back in November 1973, both Chris Everts had plenty of work left to do. While Rosen celebrated at Aqueduct, the Floridian was in Johannesburg preparing for the South African Open. “You won up here,” Rosen cabled to the tennis star. “We hope you win down there.”

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: