In one version of the story, the idea of Bobby Riggs challenging a leading woman player dated back five years or so, to a casual conversation with Billie Jean King. Riggs, the 1939 Wimbledon champion, and King, the best American woman, thought it would be a lark that they might be able to arrange someday.

By the time Bobby got serious about it, Billie Jean was no longer game. What was in it for her, aside from the $5,000 that Riggs was willing to post? If she won, all she’d establish is that she could beat a pint-sized 55-year-old. If the queen of the Virginia Slims circuit lost, the result would reflect badly on the fledgling women’s tour. Riggs could be a gentleman at close quarters, but when he set out to promote the Battle of the Sexes, he claimed that women’s tennis “stinks. A Riggs victory, he said, would prove that the ladies didn’t deserve anywhere near equal prize money.

Margaret Court accepted the challenge instead, agreeing to a best-of-three match at the remote outpost of Ramona, California. It was slated for Mother’s Day: May 13th, 1973. The clash immediately captured the public’s imagination, and not just within the tennis world. Real estate developers in Ramona kicked in another $5,000 to double the winner-take-all prize pot, and CBS television agreed to broadcast it live.

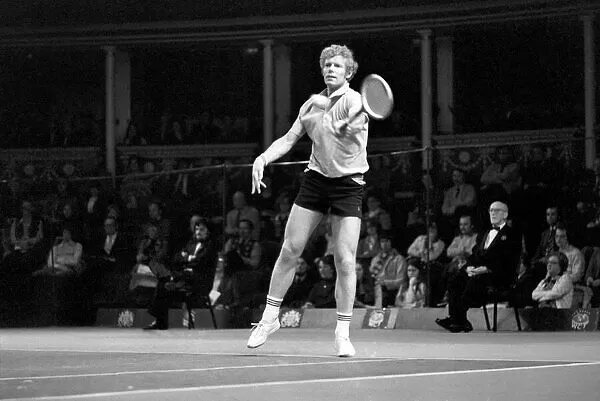

“This match is unbelievable,” said Riggs. “The eyes and ears of the world are on me. I am the greatest money player in history. I am the finest defensive player in the game. Margaret is the biggest hitter of the girls. What a match! Nobody has a clue how it will go. The mystery of the age. What a deal!”

Riggs was right about one thing: It really did seem up for grabs. Men tended to pick Bobby and women–especially fellow players–lined up behind Court. There were few precedents for a match like this. Don Budge claimed that he made quick work of Maureen Connolly when Little Mo was in her prime. Pauline Betz recalled beating a 55-year-old Bill Tilden. Fred Perry predicted that Court wouldn’t win a single game.

Billie Jean was uncertain. “If Margaret loses,” she said before the match, “we’re in trouble. I’ll have to challenge him myself.”

It was all over in 57 minutes. The kindest analysts said that Court had an off day. Riggs became a “soft wall” and junkballed his way to a 6-2, 6-1 victory. Margaret landed fewer than half of her first serves, and she struggled to generate pace against Bobby’s devilish mix of off-speed stuff. Her forehand was particularly vulnerable. Just a few days before, Budge had told Riggs to attack that wing, as Court’s style of “shoveling” that shot was unorthodox and incorrect.

The result made the front page of the New York Times, a one-paragraph item headlined, “Man Wins Tennis Match.”

For weeks, well-wishers had warned Margaret to ignore Riggs’s chatter and stay wary of his “hustle tricks.” Billie Jean suggested “psychedelic ear plugs.” In the end, none of that mattered. Bobby played his usual game of deadly dinks, and Court collapsed under the pressure. She has been criticized for unwise preparation–she practiced with hard-hitting Tony Trabert before the match–but she spent the entire week before that with coach Dennis Van der Meer, who fed her a Riggs-like mix of junk.

Bobby was gracious in victory. After accepting the winner’s check from John Wayne, he said, “If the match were played on another day under different circumstances, Margaret might easily win by the same score.”

Translation: “Please let me do this again! Please!”

Court said she was up for a rematch. The man-versus-woman concept had proven to be more compelling than anyone had hoped, and Riggs gained a type of celebrity that barely existed when he won the 1939 Wimbledon title.

King caught the match in Hawaii, on her way back from winning a title in Tokyo. When she saw how the spectacle played out, she could only groan. She didn’t trust Court to even the score with Bobby. The next day, she publicly challenged Riggs to a match for $10,000 at her club, the Shipyard Plantation at Hilton Head.

“A match with Mrs. King,” wrote Neil Amdur of the Times, “could rekindle some interest in this format.”

The circus was just getting started.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: