After twelve days of sunshine, the rain finally arrived. The women’s singles final, scheduled for its traditional Saturday, was pushed to Sunday, alongside the men’s championship match. It wasn’t exactly the equal treatment that Billie Jean King had in mind when she hinted at a boycott before the event began, but it invited its share of direct comparisons.

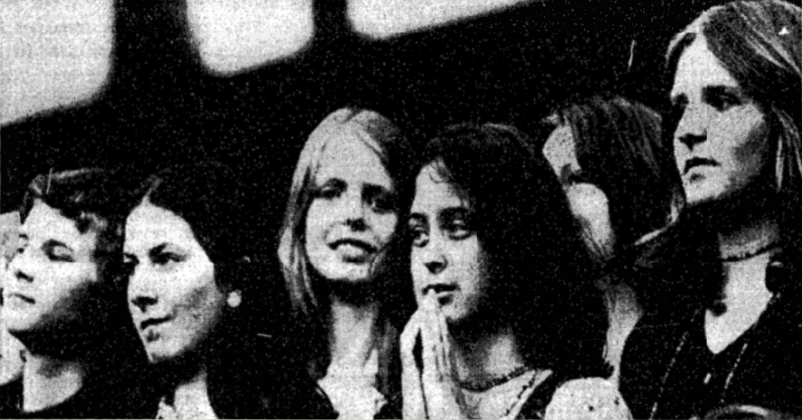

The women’s showdown, on July 7th, would feature greats of the present and future, King and the teenage Chris Evert. The men’s title came down to two Eastern Europeans, Jan Kodeš and Alex Metreveli. Both were excellent players; Kodeš had won the French Open twice in the last four years. But they were clearly beneficiaries of the 80-player ATP boycott. At this “Women’s Wimbledon,” the American ladies could claim responsibility for yet another packed house.

Billie Jean had no problem getting herself psyched up for the match. In early 1972, Evert destroyed the Old Lady on a clay court in Fort Lauderdale, allowing King just one game. While they had played three times since then, the memory was still enough to motivate the veteran.

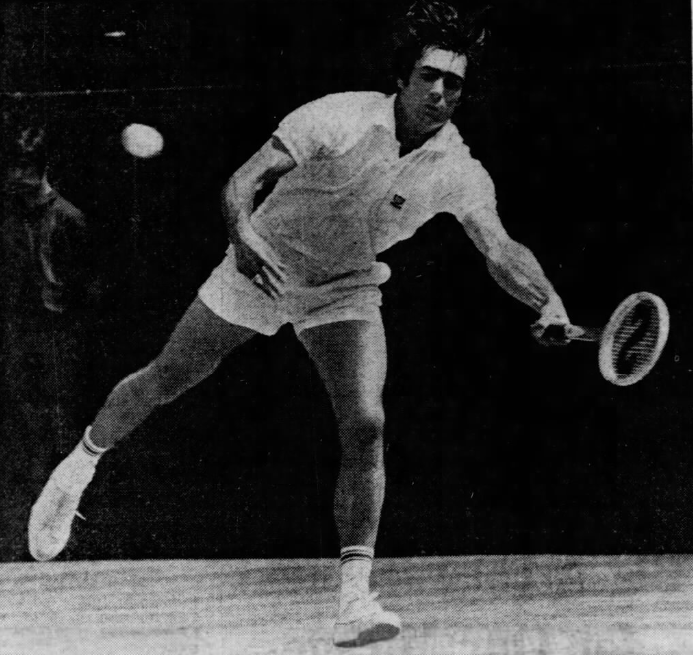

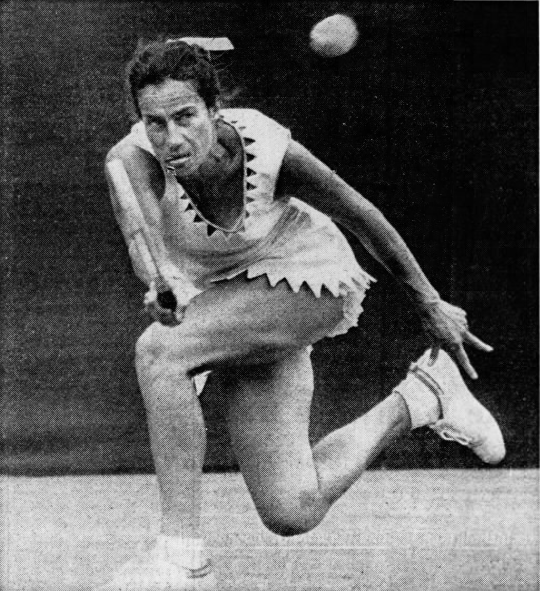

For a little while, King was on track to return the favor. She took the first set 6-0. Evert looked lost. “It was the loveliest, meanest set of tennis I’d ever seen,” wrote Grace Lichtenstein. “From the first point, she carved up Chris’s game like a Benihana chef slicing up meat on a hibachi table.”

The 18-year-old found her way back into the match, winning ten straight points as part of a push from 0-2 to 5-4 in the second set. But King wasn’t going to let this one slip away. “When I thought I was getting into it in the second set,” said Chrissie, “well, Billie Jean just served and volleyed even better. She didn’t make a mistake all afternoon.”

The final score was 6-0, 7-5 to King, in a little more than an hour. It was her fifth Wimbledon title, and she already had her eye on Suzanne Lenglen’s mark of six.

Before she could look too far ahead, though, she had two other campaigns to see out. With Rosie Casals, King polished off another title, winning the semi-finals and finals in the women’s doubles. She also teamed with Owen Davidson to take a mixed doubles quarter-final. (Their victims: Kodeš and the girls’ runner-up, Martina Navratilova.)

No one could blame Billie Jean when she skipped the traditional Wimbledon ball. She had spent five hours on court, with at least one more match to play the following day. The rest was somehow sufficient: She and Davidson came back to secure two more victories on Monday. The Old Lady had won everything there was to win, the “triple,” a feat she had also accomplished at Wimbledon in 1967.

The champion had once said, “We’ve got to get women’s tennis off the women’s pages and into the sports pages.” Mission accomplished, at least this fortnight. Newspaper editors around the world could lead with either King or Kodeš. Nearly all of them broke with tradition to focus on Billie Jean.

Madame Superstar, as couturier Teddy Tinling called her, was finally ready for a rest. She had played six matches and 139 games on Centre Court in two days. “I’m gonna sleep twenty hours a day for six days,” she told Lichtenstein. “Zonkereno!”

She already knew what her next challenge would be. It wasn’t official yet, but it had to be done. She was ready.

“Bring on Bobby Riggs.”

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: