When you think of tennis figures suffering under the yoke of casual sexism in the early 1970s, Jimmy Connors is not the first name that comes to mind.

And yet.

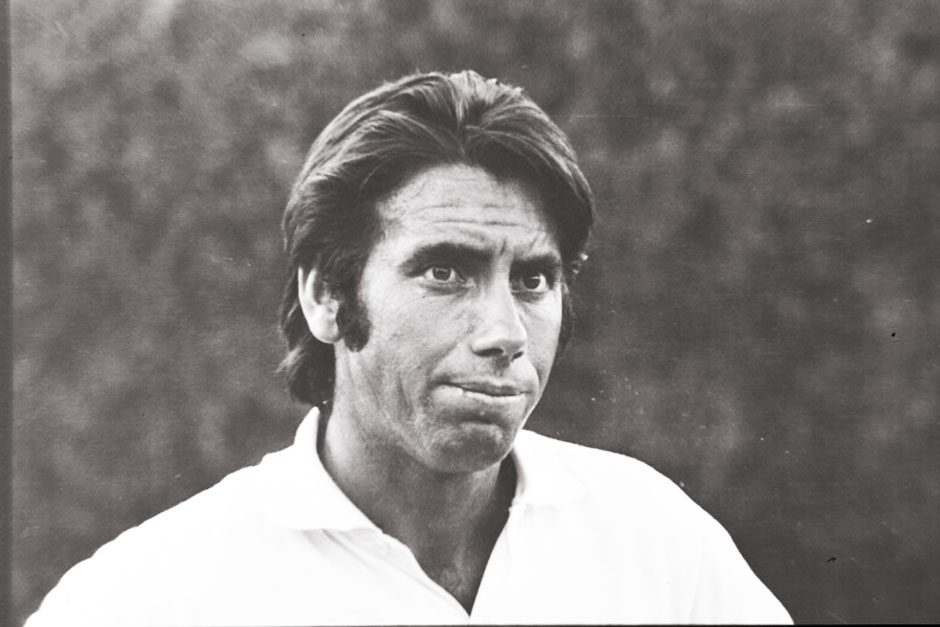

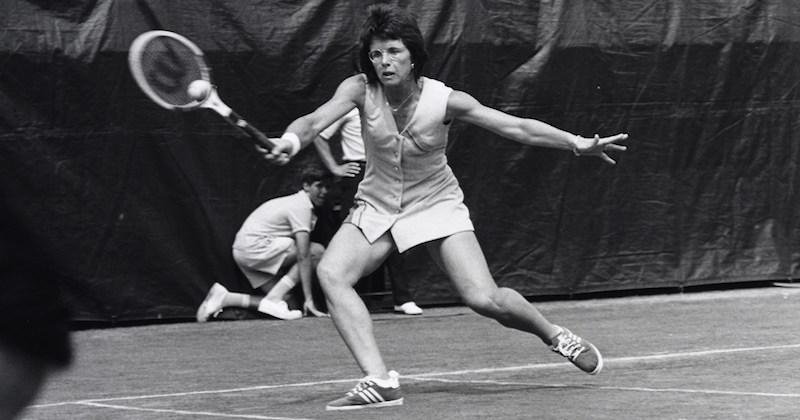

Connors, 20 years old and yet to establish himself as an equal of Stan Smith, Rod Laver, and their ilk, was best known in the summer of 1973 as Chris Evert’s boyfriend. Evert was two years younger but much further along in her career, having reached the finals at both Roland Garros and Wimbledon. Jimbo, by contrast, lost in the first round at the French and made the quarter-finals of the boycott-battered Wimbledon draw only to fall to Alex Metreveli.

When Connors recorded a series of upset victories in July, newspapermen fell all over themselves with jokes that he was more than just Chrissie’s paramour. The Atlanta Journal went with the headline, “Connors Also Plays Tennis.”

He didn’t just play, he played like no one else. On July 23rd, he sealed a sensational week with a five-set victory over Arthur Ashe in the final of the prestigious U.S. Pro at Boston’s Longwood Cricket Club. Reeling, Ashe said, “I’ve never seen a guy keep hitting so hard and deep for so long.”

Before this week, the floppy-haired left-hander remained something of an unknown quantity. He was clearly a prospect, trained from the age of three by his tennis-playing mother and grandmother, then sent to Los Angeles for graduate study with Pancho Segura and Richard González. Completing his senior year of high school in Southern California, he left early every day to practice. He joked that he studied civics in the morning, Spanish in the afternoon.

But he declined to join Lamar Hunt’s World Championship Tennis league. Instead, he competed in early 1973 on the USLTA’s “Mickey Mouse” circuit, where the only top-drawer competition came from Ilie Năstase. He said he wanted match practice, and he got that. His choice seemed to leave him unprepared for the big leagues, though. He lost to one middling opponent after another on the European summer circuit.

Longwood was his coming-out party. Unseeded, he drew the fearsome Smith in the first round. Stan was a bit fatigued, having just arrived from Sweden, and Jimbo’s attack was relentless. He put one backhand after another on the baseline, sweeping aside the number one player in the game, 6-3, 6-3. It was no fluke: The youngster backed up the victory with easy wins over Dick Stockton and Cliff Richey.

That put him in the final against the 30-year-old Ashe. The two men had never met in an official match. Arthur was a titan of the game, even if he was still prone to bouts of inconsistency. Connors, whatever his results for one week, remained unproven.

Neither man gave an inch. Ashe, like Smith, relied on a serve-and-volley attack, while Connors–with a “whippy forehand and a two fisted backhand”–made every move forward a gamble. They settled into a bruising battle, mostly from the baseline, with Jimbo going for broke and Arthur trying to coax errors from the inexperienced challenger. The youngster came within three games of victory in the fourth set, but Ashe dug out from a 40-love hole in a Connors service game and forced a decider.

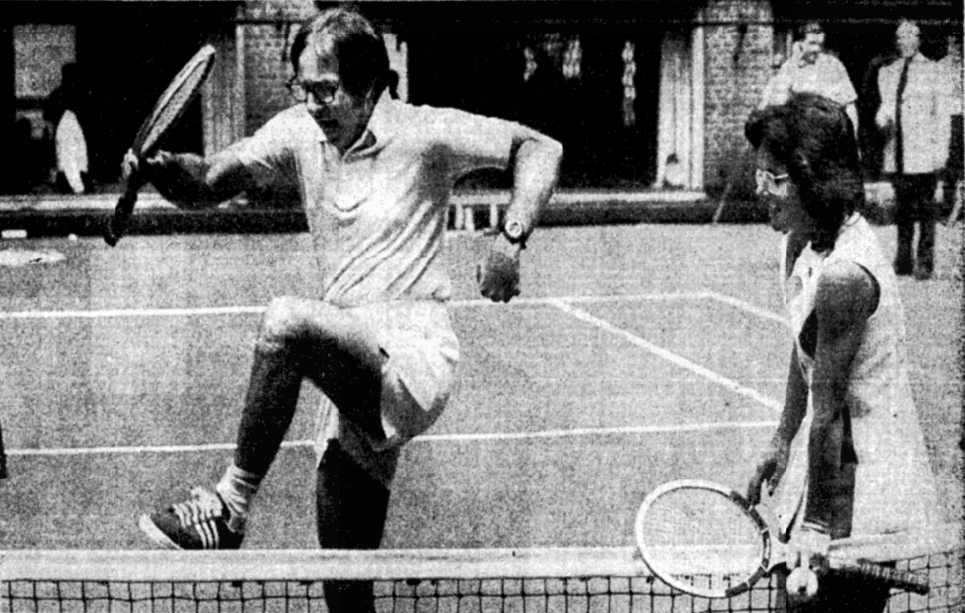

Ashe expected to find an opening. But his opponent, he said, “just kept pounding away.” The lefty may have played like a kid, but he clearly had no intention to yield, no matter how eminent the man across the net. After three hours and ten minutes, Chrissie Evert’s boyfriend took the title, 6-3, 4-6, 6-4, 3-6, 6-2.

“I never played so good in my life,” Connors said.

The crowd at the top of the men’s game had to make room for yet another contender, one who could no longer be defined by his choice of romantic partners. “For one week anyway,” Ashe said of his vanquisher, “he was in a class by himself.”

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: