The 1973 US Open reached the round of 16 without losing a single one of its eight women’s seeds. The big four of Margaret Court, Billie Jean King, Chris Evert, and Evonne Goolagong didn’t drop more than three games in a single set.

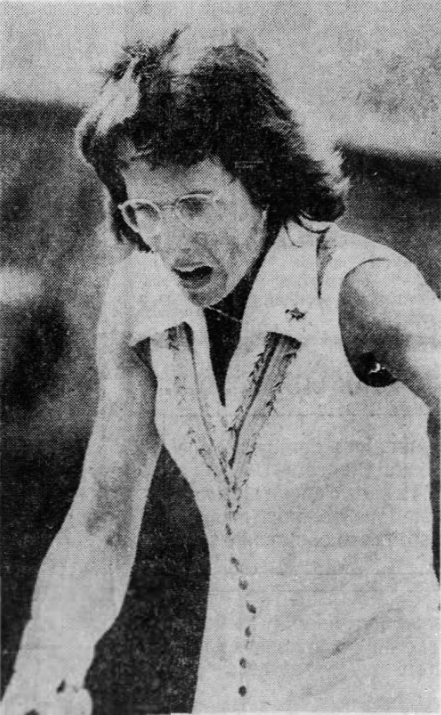

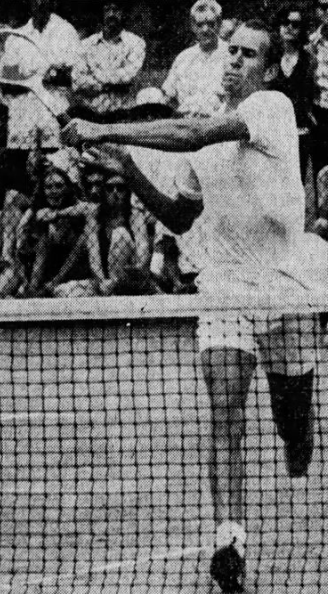

Tournament organizers expected more of the same on September 3rd. King was drawn against Julie Heldman, a fellow veteran who rarely gave Madame Superstar much of a challenge. In 18 meetings going back to 1960, Heldman had won just two. At the Virginia Slims of Boston in April, King double-bageled her.

With little hope of a close match, the ladies were assigned to the clubhouse court–Court 22–for their third-round match. Neither woman appreciated it. Billie Jean was accustomed to bigger venues, she felt she performed better in front of big crowds, and what’s more, the two-time champion deserved it. Heldman, despite her futility against King, was probably the strongest underdog in the eight ladies matches. Both competitors realized that an equivalent men’s match would’ve been scheduled on a show court.

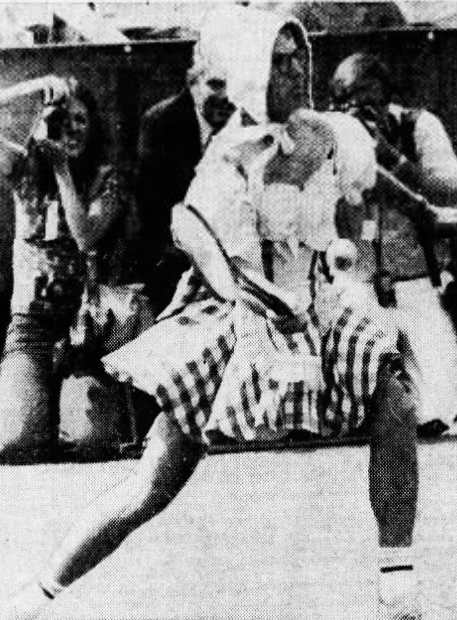

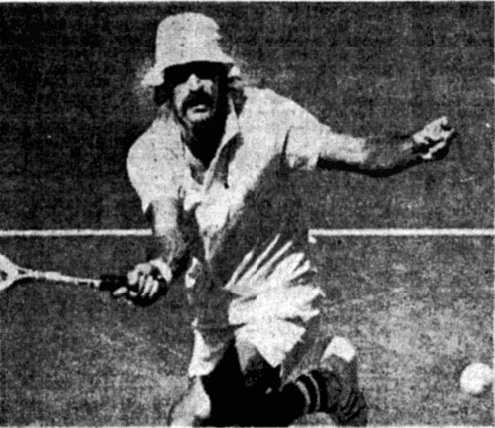

Billie Jean performed as expected in the first set, coasting to a 6-3 lead. She dominated the net, a necessity on pock-marked Court 22. Bad bounces were frequent, so the first woman to move forward had an advantage. Even in better conditions, that was usually King. Heldman tried to counter the net-rushing with a “chip and dip” strategy of low balls–slice backhands and dipping topspin forehands–that would eat away at her opponent’s energy reserves. It wasn’t enough.

Five games into the second set, trailing 1-4, Heldman finally changed her tactics. If she couldn’t beat Billie Jean at the net, she could get there first. She served better, hit her spots with the forehand, and fought her way back into contention. King was visibly tiring, no longer competing for every point.

“Billie Jean can beat anybody when she’s running,” Julie said after the match. “But when she’s not, she’s mortal like the rest of us.”

Heldman ran out the set, 6-4, and took a 3-1 lead in the second. King’s movement kept getting worse. Coming into the tournament, all eyes had been on Billie Jean’s knee, the trouble spot that knocked her out of the Jersey Shore Classic three weeks earlier. She had consulted with famed knee man Dr. James Nicholas, the expert who handled the aching joints of Mickey Mantle and Joe Namath. Nicholas suggested a light weight-lifting regimen. While King felt good entering the tournament, the knee threatened to stop her again at any time.

But it wasn’t the knee. It was the heat. Or as the New York Times put it, it was the “three H’s–heat, humidity, and Heldman.” Doubled over in pain, King elected to keep going.

Billie Jean served the next game, but she wasn’t all there. She missed a low volley on the first point and once again winced in pain. Heldman knew better than to start thinking about a victory speech–she wondered if King was pulling a trick. Neither woman was above a bit of gamesmanship, and they weren’t exactly friends. The Old Lady had feigned illness before.

Heldman broke for 4-1. After a minute on the sidelines, Billie Jean didn’t move. Finally, Heldman asked the umpire if time was up. King answered for him: “If you want it that badly, you can have it.” The top seed retired from the match.

In Heldman’s memory, it was a classless move. “She didn’t look sick when she stormed off the court,” she later wrote of Billie Jean. “And why did she quit at 4-1 down in the third? No one does that. You just stand and take your medicine.”

Tournament physician Daniel Manfredi had a different opinion. King was taking penicillin for a cold, which could be dangerous in such extreme conditions. “She was lucky she decided to stop,” said Manfredi. “She could have collapsed.”

Whatever the truth of the matter, Heldman was quickly reminded that her victory had little meaning except in the context of September 20th. In 17 days, Billie Jean would take on Bobby Riggs. Reporters were more interested in that. With a bum knee and a near-collapse, could King handle the Happy Hustler? For all her protestations to the contrary, had Riggs psyched her out?

Bobby, as he always did, spun the upset in his favor. Not only did the challenger look fragile, King’s loss opened new vistas. “I’m glad the way it has worked out,” he said. “It may just give me another champion to beat.”

So, maybe Julie Heldman?

“Hell, no,” Heldman said. “He’d psych me out of it. Anybody can psych me.”

Well, anybody except for Billie Jean.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: