For the best players, an early round at a major was supposed to be easy. A light workout, a pigeon across the net, and a victory. No need to break a sweat.

On August 30th, the second day of the 1973 US Open, everybody broke a sweat.

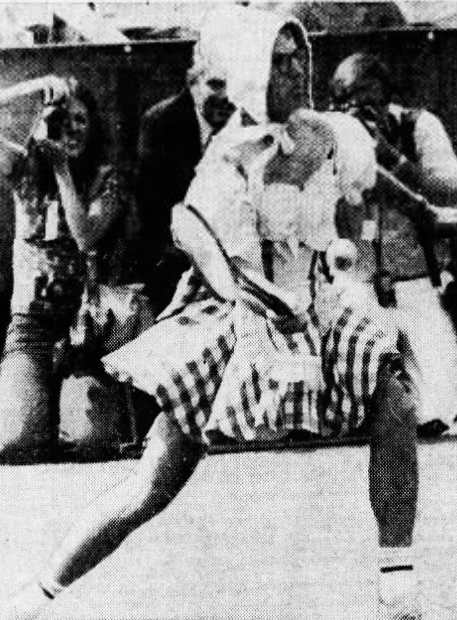

The mercury touched 98 degrees Fahrenheit. Combined with humidity typical of the New York City summer, the heat had stars racing to get off court. 30-year-old Frenchwoman Françoise Dürr was one of those who didn’t make it. Up a set and down 3-4 in the second, she retired with heat prostration against an unknown American named Sally Greer.

“I was hotter than I have ever been before,” said Dürr. Quite a statement from someone born in Algeria.

The Australians, no strangers to demanding weather conditions, fared better. Margaret Court advanced in 40 minutes. Evonne Goolagong dropped just one game. Rod Laver lost only six. Ken Rosewall and John Newcombe–allowed to compete by the ILTF after all–progressed as well.

Sweating the most was defending champion Ilie Năstase, and not just because of the sun. The unpredictable Romanian shared the top seed with Stan Smith, and fans expected a routine second-round victory when he played 24-year-old Andrew Pattison of Rhodesia. Pattison probably didn’t hope for much more, either. His career highlight to date was a run to the final at the 1972 Canadian Open in Toronto. Playing for the championship, Năstase shut him down, 6-4, 6-3.

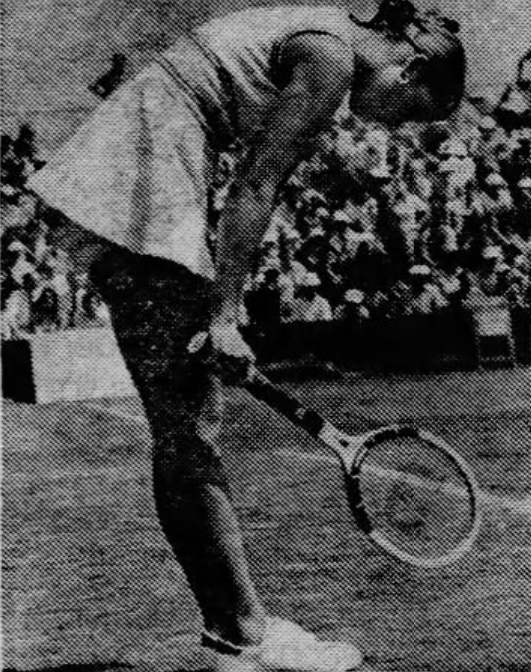

The Romanian came out cocky, joking around as he won the first two sets. Suddenly, though, the serve-and-volleying Rhodesian began playing like a world-beater. Năstase could no longer do anything with his serve, and Pattison was responding to Nasty’s deliveries with a new confidence. The underdog evened the match and broke for a 3-2 advantage in the fifth. With Năstase to serve at 3-5, tournament referee Mike Blanchard called the match for darkness. They’d pick up again in the morning.

The resumption took barely ten minutes. The top seed held, and he nearly broke for a tie. Serving for the match, Pattison earned a 30-love lead behind two big serves. He then fell to deuce before finishing the upset with two big serves and a forehand drop volley. It was a huge win for the Rhodesian, and a helpful one for Newcombe, whose draw would have pitted him against Năstase in the fourth round.

The Romanian was gone, but the heat lingered. Of all the contenders who survived, Goolagong seemed the least bothered by the conditions. Her advice: “Think cool.”

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: