In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

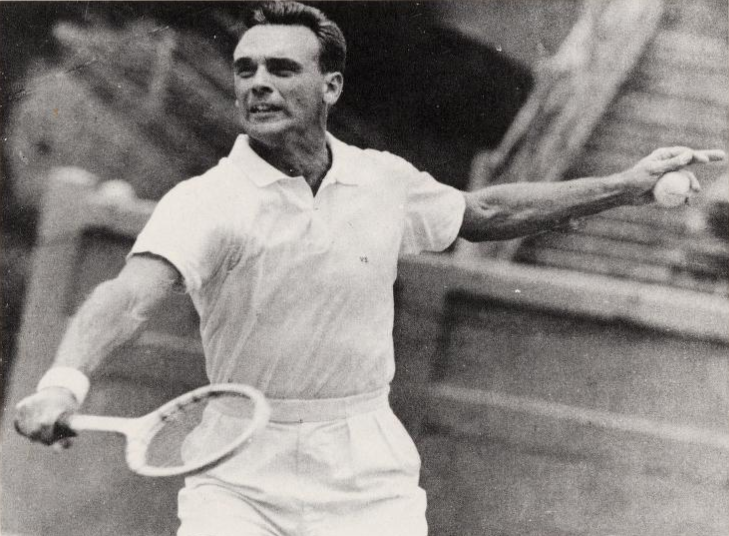

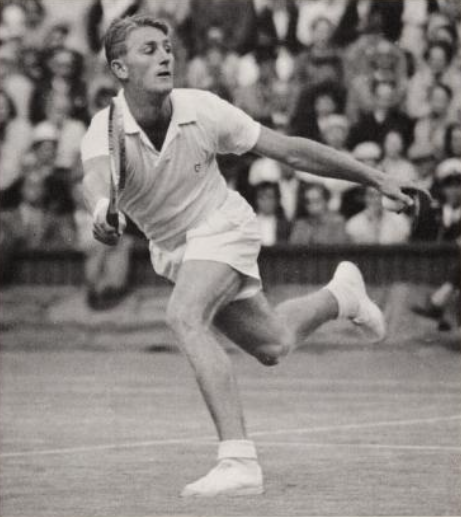

Vic Seixas [USA]Born: 30 August 1923

Career: 1940-74

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1954)

Major singles titles: 2

Total singles titles: 56

* * *

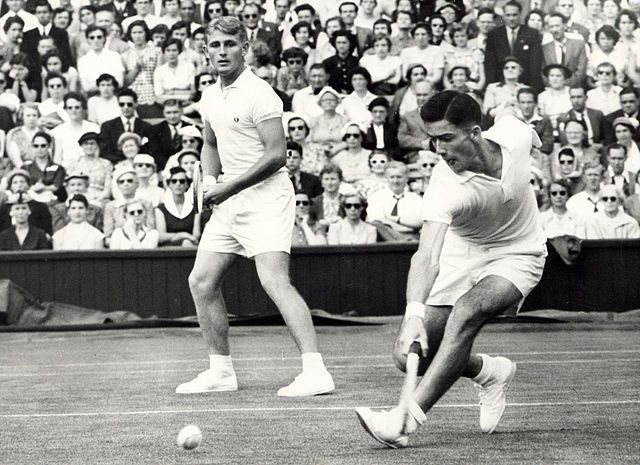

25 years before Vitas Gerulaitis and Jimmy Connors, tennis had Vic Seixas and Ken Rosewall.

Seixas did not have a lot of reason for optimism when he took the court for the second rubber of the 1954 Davis Cup Challenge Round. The Americans had lost to the Australians four years running, and worse, Rosewall owned a six-match winning streak against Seixas. The last victory was just one month old.

Years later, Vic said that Rosewall might not have been the best player he ever encountered, but he was “the toughest opponent I’ve ever faced.” Everything about the matchup tilted in the young Australian’s favor. Seixas was an expert at the net, but with an inconsistent serve and spotty groundstrokes, he didn’t always have a clear path to get there. Rosewall, 11 years the American’s junior, simply hit one passing shot after another.

Their third meeting came in the final of the French Championships in 1953. According to Rosewall’s biographer, Peter Rowley, the very first game of that match “broke Seixas’ heart.” Three of the four points were return winners for the Aussie. The fourth was a perfect drop shot. Vic made a final push in the third set, but the title went to Rosewall in four.

Still, Seixas was optimistic. Before the 1954 Davis Cup showdown, as he remembered it, he said, “Watch out, Ken, because nobody has ever beaten me nine times in a row.” It really would’ve been seven–and nine of ten–but you get the idea.

* * *

Spoiler alert: Seixas won the match. Just as nobody could beat Gerulaitis 17 times in a row (except Björn Borg), Vic was unbeatable when facing an opponent who had owned him for so long.

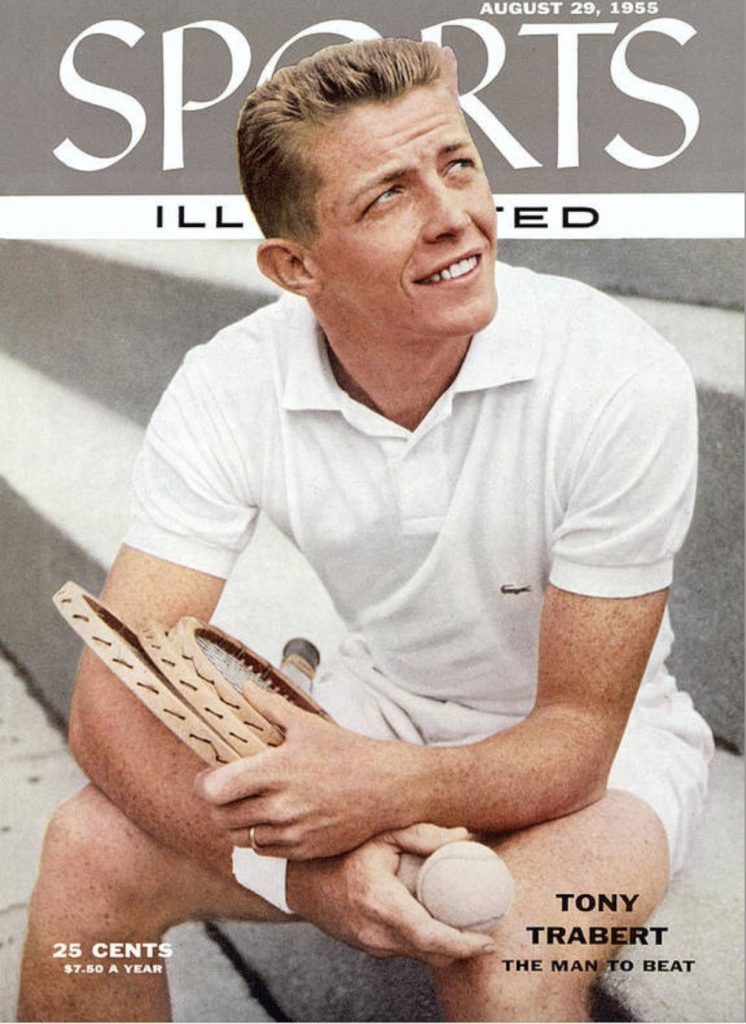

Before Seixas upset Rosewall, Tony Trabert had eked out a victory over Lew Hoad. The next day, the Americans came back out for the doubles. Vic had never been so confident. On the changeover after the Aussies forced a fifth set, Seixas told captain Bill Talbert, “Don’t worry, Cap, they’re just delaying the inevitable.”

Neither Talbert, nor anyone else in the tennis world, was accustomed to seeing such a calm, confident Vic. His last name is pronounced “SAY-shus,” giving rise to a convenient nickname of “Vexatious.” Journalist Herbert Warren Wind was kinder, punning on the name for “efficeixas” and “audeixas,” but Seixas’s querelousness was what stuck in the mind. While he was a perfect gentleman off the court, he never let a close line call go unchallenged. He was qualified as an umpire, and he never doubted that he had the best eyes of anyone on duty.

Talbert was convinced that, for Seixas, the key to beating Rosewall was mental. He described his player as “a moody veteran given to periods of deep depression and flashes of brilliance.” Once he had a game plan he felt could cope with the sharpshooting Australian, Vic was “in a happy, positive frame of mind.” Unlike in the 1953 Challenge Round, when Seixas challenged one line call far past the point of 1950s-era decorum, he remained focused throughout the four sets it took to finish off Rosewall.

The Americans triumphed, but it turned to be a mere blip in Vic’s futility against the young Aussie. They met for the last time at Wimbledon in 1956, when Rosewall won in the semi-finals, 7-5 in the fifth set. Seixas threw his racket, covered his ears to block out the cheers for his opponent, and shrugged off Rosewall’s arm after they shook hands at net.

Even though the Australians cultivated on-court diffidence to the point of apparent apathy, they respected their volatile rival. The Aussie Prime Minister R. G. Menzies, whose passion for tennis occasionally slowed the legislative gears, was prepared to forgive him anything. Vic’s behavior, Menzies wrote, “must be overlooked when you realize it is a chip of the rugged and admirable character of Seixas the Fighter on court.”

* * *

Only a few years earlier, no one would’ve thought it possible that a 30-something Vic Seixas could become both Wimbledon champion and Davis Cup hero.

He started early, picking up the sport in his hometown of Philadelphia at age 5 or 6. He could beat his father–“a mediocre club player”–within two weeks. He earned a tennis scholarship to Penn Charter high school, and he came within one point of beating Budge Patty for the national junior title.

Then World War II intervened. He spent most of the conflict in the South Pacific, testing and ferrying airplanes for the Army Air Corps. Returning to civilian life, he went to school at the University of North Carolina, where he won 63 of 66 interscholastic tennis matches and played guard on the basketball team. A multi-sport star who also excelled at squash, he always considered himself an athlete who happened to play tennis. Had tennis not worked out, he said, he would’ve given his all to baseball instead.

By the time Vic graduated, a future as a “frustrated baseball player” seemed a lot more likely than an international tennis career. Sports Illustrated explained in 1957:

By every reasonable law of athletics, he should have had no international career at all. If a tennis player is going to develop into a star, he invariably gives definite indications of this when he is in his early 20s. By 27 he is on the way down. Seixas began when he was 27.

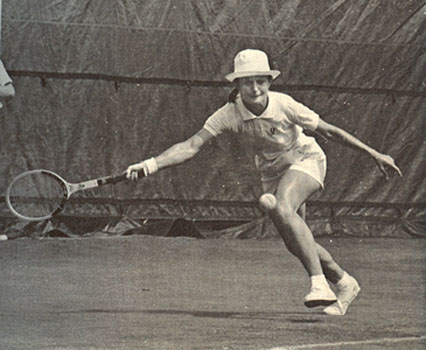

He was a mere “regional lion” at the start of 1950. But sent on a tour abroad that year with Art Larsen, Doris Hart, and Shirley Fry, he reached the quarters at the French and the semis at Wimbledon. The busy schedule of a touring player suited him. In eight attempts at Forest Hills as a junior or a part-timer, he had never surpassed the fourth round.

* * *

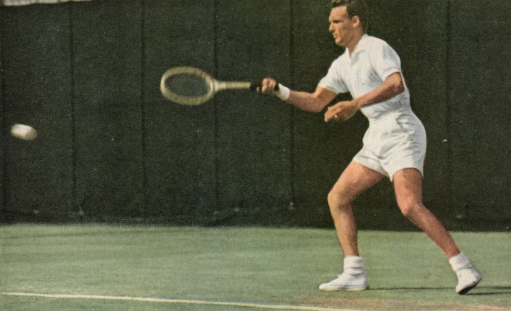

Seixas played the kind of tennis you’d expect from a late bloomer. Nothing about his game was sensational, except perhaps his volleys. His kick serve was fluid and reliable, but he couldn’t always control his more powerful first delivery. His groundstrokes were compact; neither the loopy forehand nor the sliced backhand functioned as much of a weapon.

These were hardly the strokes of a champion. Australian Davis Cup captain Harry Hopman considered him the most unorthodox of the top ten. A friend told Seixas, “After many years you’ve gained control of basically unsound shots.”

What set Vic apart was sheer tenacity. Like David Ferrer a half-century later, Seixas fought for every point. While that level of persistence has become standard for a certain type of 21st-century competitor, it was extremely rare in the amateur era. The “Big Game” style played by Jack Kramer, Ted Schroeder, and Trabert coupled aggressive serve-and-volleying with periods of rest. Few players were ashamed to tank the third set after winning the first two.

Seixas took full advantage of the conventional wisdom. When an opponent let down his guard, he pounced. Even on his best day, he would have had no chance against an in-form Lew Hoad. But Hoad could rarely sustain the all-time-great shotmaking that his peers still rave about. Lew straight-setted Seixas three times, but Vic led their career head-to-head, six matches to five.

Going hard on every point required a level of conditioning that most of Vic’s peers didn’t even attempt. The Hopman-trained Australians did, and that was part of what kept them on top. Seixas was one of the few men who still stood a chance if he found himself in a fifth set against a Hopmanite.

The combination of superior fitness and persistent fight also earned him laurels that his raw talent didn’t obviously deserve. At Wimbledon in 1953, Seixas fought off Hoad in the quarter-finals, winning a 9-7 fifth set. In the semis, he lost the second and third sets to Australian left-hander Mervyn Rose, 12-10 and 11-9. Vic had more left in the tank, and he came back from the two-sets-to-one deficit to win. Rosewall had lost early, so all that was left for Seixas was a routine straight-set victory in the final over the unseeded Dane, Kurt Nielsen.

Seixas realized that the draw broke his way. Rosewall probably would’ve gotten the better of him. But he always said he didn’t want to “belittle” his own accomplishment, and rightfully so.

Vic reached the quarter-finals of a major 20 times in his career, including 10 semi-finals and 5 finals. If you give yourself that many chances at the ultimate prize, you’ll eventually find fortune on your side.

He took advantage of another set of favorable developments at Forest Hills in 1954. He had been entering the US National Championships almost every year since 1940, when he won a match as a 17-year-old and nearly ousted Frank Kovacs. He had reached two finals, losing to Frank Sedgman in 1951 and Trabert in 1953.

In 1954, none of Vic’s nemeses got in the way. Sedgman had turned pro. Hoad lost a marathon quarter-final to the underachieving American Ham Richardson. Both Trabert and Rosewall lost to Rex Hartwig, an Australian whose extreme highs and lows made Hoad look like an accountant. Seixas probably wasn’t the best player in the draw–though Hopman would put him at the top of his year-end list–but he was far too steady for Hartwig in a four-set final.

* * *

Seixas tends to be remembered as a second-class great, behind Trabert and all those Australians. Sportswriter Al Laney showered him in backhanded praise, describing Vic as one of a few players “who went very far in the game, and gave us some of our most pleasurable moments, not so much because they really belonged on the highest rung of the ladder but because they were such indomitable fighters.”

Jack Kramer was more direct. He never offered Seixas a pro contract because he “was simply not good enough.” He wrote, “Seixas [and a few others] were smart enough to realize that the only reason they won in the amateurs was because the best players had turned pro.”

Maybe. Seixas, Trabert, Rosewall, and Hoad all would’ve had a harder time if Kramer and Richard “Pancho” González had been contesting Wimbledon and Forest Hills every year. Kramer was only two years older than Vic, and González was several years younger, but they crossed paths only at the beginning of Seixas’s time as a star. Whether he was “good enough” or not, Vic held his own against the best amateurs of the 1950s in the year or two before Kramer deemed them worthy of professional deals.

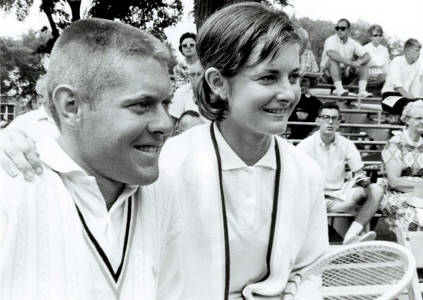

Beyond the major titles and the 1954 Davis Cup, Seixas’s legacy rests in his astonishing longevity. He ultimately played Forest Hills 28 times, and he lost in the first round only twice. In 1966, he had long been a part-time player again, working as a stockbroker in Philadelphia for Goldman Sachs. Yet at the National Championships, he outlasted a cramping Stan Smith, 23 years his junior. Earlier that summer, he won a three-and-a-half-hour match against 22-year-old Australian Davis Cupper Bill Bowrey.

Now, a month away from his 99th birthday, Seixas is the oldest living Hall of Famer. (“I’d rather be the youngest,” he likes to say.) Even amid such a sterling crowd, Vic continues to outlast the competition.