In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

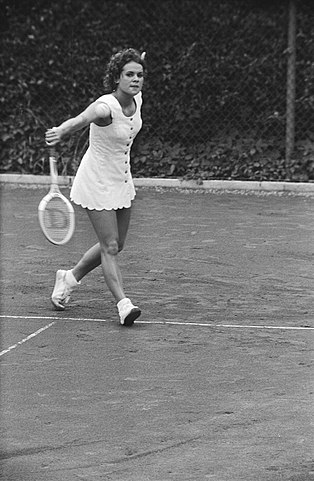

Tracy Austin [USA]Born: 12 December 1962

Career: 1977-83 (and brief comebacks until 1994)

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1980)

Peak Elo rating: 2,369 (1st place, 1980)

Major singles titles: 2

Total singles titles: 30

* * *

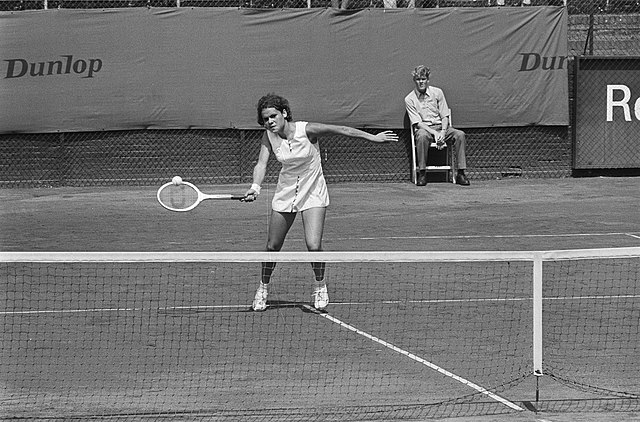

Everything Tracy Austin did, she did younger than anyone else. She was on the cover of World Tennis when she was four years old. Sports Illustrated announced that “A Star Is Born” in 1976, when she was 13. She won her first pro tournament a year later.

Somehow, the barrage of age records aren’t what sets Austin apart. Women’s tennis has seen prodigies come and go for a century, from Suzanne Lenglen and Maureen Connolly to Jennifer Capriati and Coco Gauff. Tracy was part of a particularly precocious charge, leading a generation that included Pam Shriver, Andrea Jaeger, and Kathy Rinaldi, among other teen starlets.

The striking, unusual aspect of Austin’s career is that, when she arrived on tour as an eighth-grader, she was already essentially a pro. She didn’t take any prize money in 1977 for her debut victory at the Avon Futures of Portland, as she was technically an amateur. But I mean “pro” in the figurative sense. She was tactically sound, mentally prepared, and PR-savvy, at least as much as any 14-year-old could be.

She was the first child star of the big-money WTA era. Within a decade of her appearance on tour, the women’s circuit would put age rules in place to protect young players. (Ironically, Wimbledon lifted its rule to allow Tracy to play in 1977.) Yet at first, Austin made those regulations look unnecessary. Until her body began to betray her, there was no sign she needed to be shielded from anything. Plenty of teens would do too much, too soon, but Tracy insisted to Bud Collins in 1994, “It wasn’t burnout. I’ve never been burned out.”

She set the tone for the millionaire prodigies of the decades to follow. Her mother traveled with her full-time, so she made few friends on the tour. She fearlessly stared down women she ought to have idolized, like Chris Evert. Others, such as Martina Navratilova, she annoyed into submission.

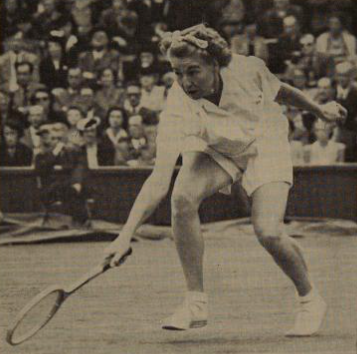

Most of all, Austin played like an adult, no matter how much her pinafores and pigtails made her look like a child. For about a year, she was a curiosity, a five-foot-nothing retriever with nothing but potential. After that, though, the rest of the tour had to grapple with a new reality. The unprepossessing highschooler in braces was a killer.

* * *

Austin came by her precocity honestly. Her mother, Jeanne, took up tennis with a vengeance as an adult, and she dragged her five kids to the club with her. Tracy was the youngest, and three of her siblings–Pam, Jeff, and John–also played at the pro level. Growing up in Southern California, they could practice year round.

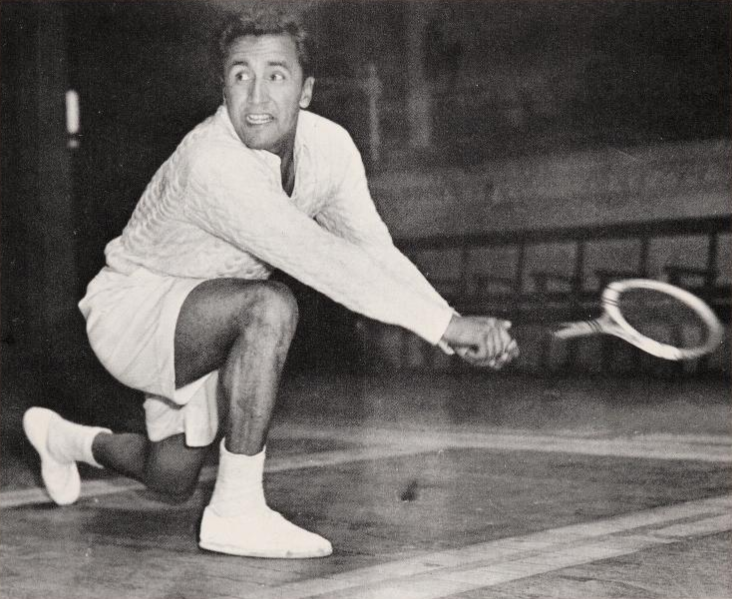

Based at Jack Kramer’s club in Los Angeles, the Austins had access to some of the region’s best coaches. Tracy’s first coach was Vic Braden. Braden told a reporter in 1976 that, even before her first birthday, he would roll a ball inside her crib. “Back then she sliced the backhand,” he quipped.

A few years later, Robert Lansdorp took over. Lansdorp became known for his groundstroke expertise, a reputation he owes at least partly to Austin’s prowess from the baseline. He would remain in Tracy’s camp, with only short breaks, for the rest of her career. He considered her a “mental giant” from an early age, and in 1980, he predicted, “[S]he can be the greatest ever.”

It became increasingly difficult to find anyone to argue with him. Austin reached the quarter-finals of her first US Open, in 1977, upsetting Virginia Ruzici and fourth-seed Sue Barker. In nine WTA events as a 14-year-old, she lost in the first round only once. A year later, she won two top-level tournaments and recorded her first upset over Navratilova. In 1979, she won the US Open, knocking out both Evert and Navratilova to become the youngest ever to hoist the trophy there.

The aspect of Austin’s game that everyone noticed–opponents in particular–was her sheer determination. “Tracy obviously had something, especially mentally, almost better than just about anyone else,” said her one-time rival Shriver. “She didn’t break down under pressure.”

When Tracy beat Barker, Billie Jean King said, “Wait until she learns how to choke.” Billie Jean was still waiting nearly three years later. In the semi-finals of the 1980 Avon Championships, the teenager beat her for the fifth time in a row.

* * *

There was a lot of waiting in Austin’s game. Broadly speaking, she was a Chrissie clone. Both women sported a two-handed backhand and the doggedness to use it until the woman on the other side of the net missed. Neither had a strong serve–Braden described Tracy’s as a “baby-puff” delivery–but the rest of their games were so airtight that it didn’t matter.

In Austin, Evert met her equal. The Match Charting Project has logged two of their clashes, each of which averaged an astonishing nine shots per point. The battles themselves could be soporific, but the outcomes–which the pair split almost down the middle–were of critical importance.

How you rate Tracy depends a great deal on how much weight you give to her victories against Evert. Austin scored her first upset at the 1979 Avon Championships, in their fourth meeting. She won again at the Italian Championships two months later, breaking Chrissie’s 125-match win streak on clay. The US Open final later that year was the first of five consecutive wins for the younger woman, including three in the space of ten days in January 1980.

Evert won only ten games in the last three of those matches–combined. She declared she was burned out, and she took a three-month break from the tour. Sarah Pileggi, writing for Sports Illustrated, was ready to mark the end of an era. For Pileggi, Evert and Evonne Goolagong had defined the previous epoch; Austin and Navratilova were the stars of the future.

It didn’t work out that way, of course. Chrissie returned from her sabbatical with something to prove. She won the French Open (Austin wasn’t there–it conflicted with exams), reached the Wimbledon final, and won the US Open, beating Austin in the semi-finals there.

Still, Tracy was far from ready to concede the spotlight to her elder. She beat Evert in the Toronto final the next year. At the 1981 season-ending championships, the two women met at the round-robin stage, where they fought for 3 hours and 18 minutes. A single 26-point game required more than 500 shots. Evert won in a third-set tiebreak, but it was a pyrrhic victory. They met again in the semi-finals, where Austin proved relentless. The teenager reeled off nine straight games, getting her revenge, 6-1, 6-2.

* * *

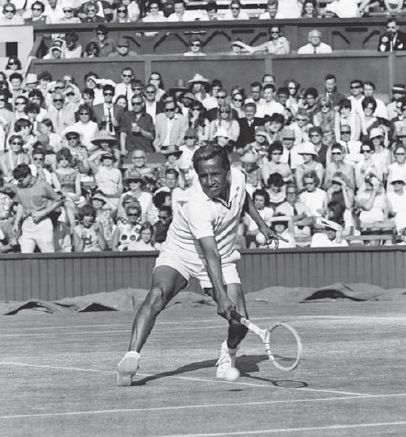

Chrissie wasn’t the only giant that Austin had to slay. When Tracy arrived on tour, Martina Navratilova was nearly as fearsome. The transplanted Czech had won a major every season since 1975, and she lost only 10 of her 90 matches in 1978.

Navratilova, with her lefty serve and attacking game, posed a very different sort of challenge to the newcomer. Fortunately for Tracy, her own style would prove to be particularly irritating to Martina.

Austin broke through in her fourth match against the left-handed star. In the quarter-final of the 1978 Virginia Slims of Dallas, when Tracy was still only 15, she halted a 37-match win streak of Navratilova’s. The generational clash went to a third-set tiebreak. At the time, breakers were best of nine points. The ninth point was for all the marbles, if it came to that–no need to win by two. Austin was fearless even by her own standards, serve-and-volleying at 4-3, only to see her opponent pass her with a diving forehand. On the deciding point, she rushed the net again, and this time she put away a volley to finish the upset.

Their encounters weren’t always so thrilling, especially not for Martina. Austin delivered another upset at the Avon Championships of Washington, the first tournament of the 1979 season. Chasing down yet another lob en route to a 6-3, 6-2 loss, Navratilova said aloud, “It’s so boring I can’t stand it!”

In one two-and-a-half-year span, from July 1979 to the end of 1981, Austin won 11 of 17 meetings. (Overall, Navratilova finished the career series ahead, 21-14.) The matchup never got any more interesting for Martina. After winning a three-setter at Filderstadt in 1981, Tracy excitedly told her coach, “Once I lobbed three times in a row and she yelled, ‘Boring!’ right in the middle of the point. I couldn’t believe she did that! I decided right then I would do it some more.”

Austin wouldn’t be around to grapple with Martina much longer, but her influence would linger. Navratilova’s struggles with pesky, determined opponents like Tracy played a big part in her early-1980s decision to devote herself even more wholeheartedly to training and become the fittest player that women’s tennis had ever seen.

* * *

It’s possible to tell a story of late-1970s tennis in which Austin was just lucky, coming along at the right time. Evert was distracted by her marriage to John Lloyd, and Navratilova had yet to fully dedicate herself to the game. If you can’t think of Tracy as more than a pigtailed moonballer, it’s a convenient narrative to hold onto. It’s true that Chrissie wasn’t quite as deadly as she had been a few years before, and Martina wasn’t as overpowering as she’d become.

But we need to be careful not to get the cause and effect backwards. In 1980, the season when Austin took over the number one ranking and knocked Evert off the tour entirely, Chrissie won 72 of 79 matches. Navratilova won 91 out of 104. Even slumping, the duo was nearly untouchable.

Over her entire two-decade career, Martina lost more often to Austin than she did to anyone else except for Evert. Only two women–Navratilova and Goolagong–tallied more career wins against Chrissie than Austin did. With only a bit of exaggeration, we can compare Tracy’s achievement to that of the early-career Novak Djoković, who forced another dominant twosome to make room at the top.

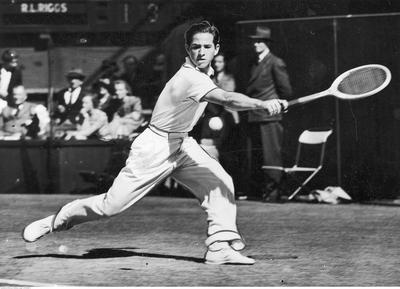

Credit: Los Angeles Times

Unfortunately, the similarities between Novak and Tracy go only so far. By the time the 19-year-old Austin won her second major at the 1981 US Open, she was already coping with the injuries that would end her career. Sciatica sidelined her for the first four months of 1981, and it caused her to miss the same span in 1982. She sputtered through a 1983 campaign, and aside from a few brief comeback attempts, her career was over.

Her remarkable mental strength probably disguised a fragile, growing body that wasn’t ready for the rigors of full-time training and tournament play. Evert played nearly as much as a youngster, but she grew up on clay courts, while the Austins developed their games on more punishing cement surfaces. And Tracy, with the determination of a player twice her age, rarely paced herself in competition. We might remember her for her moonballs, but when she hit for winners, she gave it all she had. When Austin was hitting at full force, moonballs were what came back.

While it’s tempting to speculate on what might have been, Austin’s teen years showed us, more or less, what she was ever likely to accomplish. Yes, she could’ve won dozens more tournaments, perhaps even another several majors. But what we saw was, more or less, what we would’ve gotten. At age 21, the veteran’s game was not that different than the one that made her a pre-teen champion, an imperfect but complete package. In 1973, the Austin family asked for advice from the legendary Australian coach Harry Hopman. Seeing the 10-year-old play, he demurred. “What do you tell a genius?”