Credit: Los Angeles Times

In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Arthur Ashe [USA]Born: 10 July 1943

Died: 6 February 1993

Career: 1959-79

Played: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak ATP rank: 2 (1976)

Peak Elo rating: 2,206 (2nd place, 1976)

Major singles titles: 3

Total singles titles: 87

* * *

Nearly thirty years after his death, Arthur Ashe is best known as the name on a building–the largest tennis stadium in the world.

Before that, Ashe was an activist and humanitarian. In retirement, he was one of the most authoritative voices on the subject of race in sports. But he was too curious to be limited to a single topic. He would speak out on anything that caught his attention and triggered his sense of injustice.

When his HIV diagnosis became public knowledge–very much against his wishes–he immediately turned much of his remaining energy to HIV/AIDS-related causes.

Before that, Arthur was a prolific, best-selling author. His magnum opus, A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African-American Athlete, was an enormous, unprecedented project. When no publisher would take on the expense, he raised the funds himself, then supervised the research. He couldn’t believe how little was known about Black sports before Jackie Robinson.

Before that, he was already an elder statesman in tennis. He captained the U.S Davis Cup team, handling the unenviable task of motivating both John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors. Ashe appeared regularly as an analyst, offering detailed, technical explanations of the game. He refused to talk down to his audience.

Before that, he was a Wimbledon champion, an unexpected victor over Connors in 1975. Seven years earlier, he won the first US Open. He was still an amateur then, so while he beat Tom Okker for the title, Arthur settled for modest expenses while the Dutchman took home prize money of $14,000.

It goes without saying that Ashe was the first Black man to accomplish virtually all of those things.

Even before Arthur won the US Open, sportswriters poked fun at the way in which every media mention of the young star had to describe him in racial terms. He was “the first Negro” on the Davis Cup team, the first to win this or that national championship, and so on. There were a lot of firsts. One 1964 squib in the New York Times spanned all of three paragraphs–and used the phrase twice.

Arthur Ashe is, justifiably, a legend. So much so that the messy details of his personality and his game tend to get lost. So much so that it’s daunting even to write about him. The best tennis book ever written–John McPhee’s Levels of the Game–is half about Ashe. Four years ago, Raymond Arsenault published an excellent, 784-page biography of the man.

I don’t claim any special insight that McPhee, Arsenault, or Ashe himself hasn’t already put on record. Instead, I want to look back at Arthur before that first major title. As early as his teens, he demonstrated many of the qualities that would define both the veteran superstar and the later public intellectual.

His game didn’t peak until the mid-1970s, but Ashe was one of the most fascinating figures in 1960s tennis.

* * *

The New York Times gave Ashe his first extended notice in 1963, when the 19-year-old was named to the United States Davis Cup team.

Frank Litsky wrote that Arthur “suffers from an embarrassment of riches. His repertoire of tennis shots is too large for his own good…. His understanding of the game and agility leave little to be desired. But he lacks experience and frequently makes the wrong shot.”

Ashe provided much of the material himself: “What good are 10 types of backhands when I don’t use the right one automatically at the right time?” And: “I tend to be lazy with my forehand.”

There was always a whisper of latent racial stereotyping. The six-foot-one-inch, rail-thin teenager had prodigious physical gifts, but he didn’t yet have the necessary mental qualities to become a champion.

Even as a teenager, Arthur was more complicated than that. Yes, his mind wandered during matches–he was the first to say so, and he’d go into detail about what distracted him. (In one 1965 final against John Newcombe, it was a stunning Trinidadian stewardess named Bella.) Journalists rarely needed to analyze Ashe matches for themselves–the player himself would offer more detail, positive and negative, than they could ever fit into their stories.

Ashe also saved reporters from the awkwardness of writing about race. He was always the most perceptive observer of his unique position as a Black prodigy in the whitest of sports. He said in 1963:

I wouldn’t like to feel that I am considered a representative of the Negro race, but I know I am. I just want to be taken as another tennis player. If I make it, fine. If I don’t–well, lots don’t. I know the odds are against me because there’s only one of me now.

* * *

Even at age 19, Arthur realized he’d never be just another tennis player. Still, he amazed fellow players with his casualness. He didn’t feel any pressure from posterity, and he sometimes echoed one of his father’s mantras. Arthur Sr. liked to say, “No one will care a hundred years from now.”

Ashe’s unexpressive on-court demeanor had a different explanation, though. The men who helped him as a youngster realized that he could very well end up making history. They insisted he behave accordingly.

Dr. Robert Johnson was an energetic talent scout and coach who took on the ten-year-old Arthur. He knew that his young Black charges would need to comport themselves impeccably to avoid problems in the white tennis world. Between backhand drills, he urged his boys to remain calm, never make a scene or argue with an official, and give the benefit of the doubt to opponents who probably wouldn’t do the same in return.

No one learned those lessons better than Ashe did. He may not have needed them at all. He was so relaxed on court that fans occasionally suspected he didn’t care. He reached the final of the 1966 Australian Championships, where he faced Roy Emerson. He lost the last point on a foot fault, and Emerson showed more disgust with the ruling than he did.

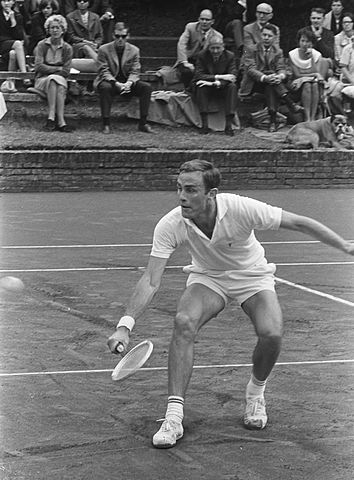

Ashe and Emerson in 1965

By 1966, Ashe was one of the best players in the world, with a résumé that included several defeats of Emerson himself. But such non-displays left the question open: Did he have the killer instinct necessary to win the most important titles?

Arthur, as usual, had an opinion. He told Frank Deford later that year:

Do I have a killer instinct? No. Sorry, I just don’t have a killer instinct. I play the game. That’s me. I give it all I’ve got–people are wrong about that–but if it’s not enough I figure they’ll just get someone else.

When John McPhee asked Ashe’s first coach, Ron Charity, he got a very different answer:

People say that Arthur lacks the killer instinct. And that is a lot of baloney. Arthur is quietly aggressive–more aggressive than people give him credit for being. You don’t get to be that good without a will to win. He’ll let you win the first two sets, then he’ll blast you off the court.

* * *

Killer instinct or not, no one would question Charity’s implication that Ashe could take his game to stratospheric heights. At Forest Hills in 1965, the 22-year-old put the tennis world on notice with a quarter-final upset of Emerson, the reigning Wimbledon champion. After three hard-fought sets–13-11, 6-4, 10-12–he delivered the knockout fourth-set blow in just 17 minutes.

Every match he contested was decided on his own racket. George Toley, the University of Southern California coach who had ample opportunity to watch Arthur when he represented UCLA, said, “He wins or loses every match. Nobody really beats him in that sense.”

In early 1966, Ashe played a practice set against Richard “Pancho” González, the standout pro who remained one of the strongest players in the world at age 37. Ashe won, 6-0. González could be stingy with praise, but not this time. “I was really trying. I tell you, it was the greatest set of tennis I ever saw played. Yes, including any of the ones I played.”

Arthur’s serve, as well as the rest of his game, relied on coordination and strong wrists. Detractors would sometimes call his style “wristy.” His strokes weren’t as sturdy as they could be, and that probably contributed to his streaky nature. Still, wristiness was hardly a death knell. The other star player of the decade known for his wristy shots was Rod Laver.

The wrist action made his backhand particularly devastating. McPhee wrote, “Tennis players fear Ashe’s backhand and say that hitting a second serve to it can be like serving into the mouth of a cannon.” Arthur had the ability to wait until the last second to commit to a direction. At the 1968 US Open against Cliff Drysdale, he hit one such shot that was so hard and so unexpected that Drysdale–even though he was in position–didn’t lift his racket.

At his best, Ashe hit all of his shots like that. One of those veins of form turned up for the fourth set of the 1968 US Open semi-final, the match chronicled in Levels of the Game. McPhee wrote:

Ashe now begins to hit shots as if God Himself had given them a written guarantee. He plays full, free, windmilling tennis. He hits untouchable forty-five-degree volleys. He hits overheads that skid through no man’s land and ricochet off the stadium wall. His backhands win everywhere–crosscourt, down the line–and one of them, a return of a second serve, is almost an exact repetition of the extraordinary shot that finished the third set. “When you’re confident, you can do anything,” Ashe tells himself.

When Arthur was confident, he could do anything. His opponents could only wait for the moment to pass. Clark Graebner, Ashe’s opponent in that match, said, “I didn’t know he’d go ape.”

* * *

There was an enormous gap between Ashe’s best and worst games. After beating Emerson at Forest Hills in 1965, he fell in the next round to Manuel Santana, a weaker opponent. He was the hero of a 1965 Davis Cup tie against Mexico, but his punchless performance was the prime cause of a loss to lowly Ecuador in 1967.

Still, it’s easy to take this line of thinking too far. From 1965 until he turned pro, he was one of the best amateurs on the circuit. According to my historical Elo rankings, the 22-year-old was already the fifth-best player in the game–amateur or professional–at the end of 1965.

On an Australian tour in 1965-66, Ashe claimed four of the prestigious state tournaments Down Under, winning finals against Emerson, Newcombe, and Cliff Richey. He won six titles in 1966 and eight in 1967, and he reached the final round of the Australian Championships both years.

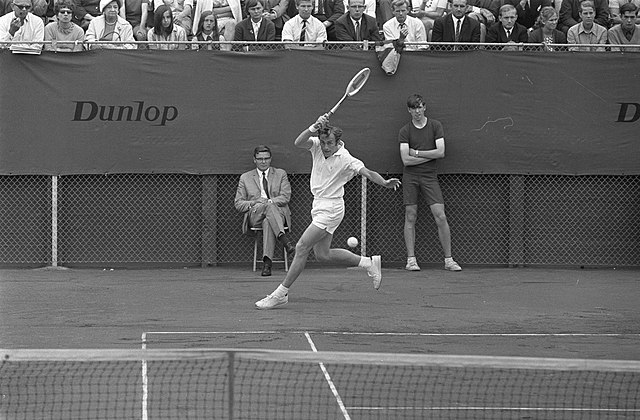

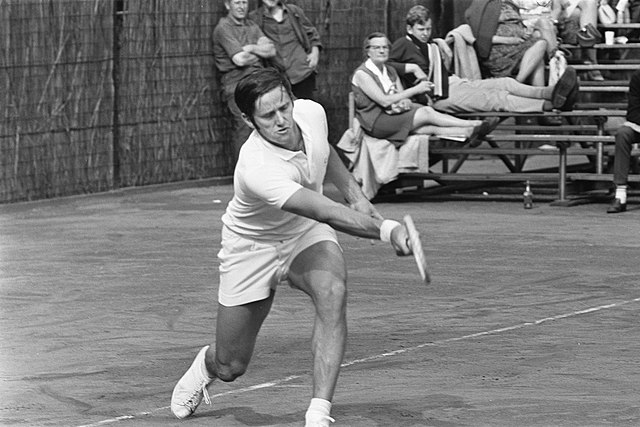

Arthur in 1967 or 1968

He gave journalists some ammunition for their “inconsistent” tags, sometimes going as far as showboating in early-round matches. He still had more shots that he knew what to do with, and when a victory was assured, he would sometimes look terrible, spinning and dinking his way to a roundabout win.

But unlike players who couldn’t harness their talent and resorted to outright clowning, Ashe understood when to put that side of himself away. His college coach, J.D. Morgan, said in late 1965:

[I]n tough matches, particularly when he’s behind, Arthur sticks with basic stuff. [His imagination is] an asset. There never was a tennis champion without imagination, who never came up with the unexpected–a great shot, not always basic–at a critical time.

At match point against Graebner at the 1968 Open, he told himself to play it safe. But when a second serve spun toward his backhand, he crushed it. Imagination? Carelessness? Does it matter?

* * *

Arthur’s game made him one of the most popular players on the circuit. His role as the only notable Black man in the sport kept him in the papers. No one understood that as well as Ashe himself.

The mid-to-late 1960s were the peak of “shamateurism.” McPhee wrote that a top amateur player could bring in $20,000 a year from endorsements and expense money–well north of $150,000 in today’s dollars. One anonymous admirer sent Ashe nearly $10,000 worth of General Motors stock.

Ashe had long since gotten over any wish to be just “another tennis player.” Ron Charity told Sports Illustrated in 1966, “Arthur has a very keen, uh, let us say, marketing sense.” Ashe studied business at UCLA, and he couldn’t help but think about his tennis in those terms:

Let’s face it. Being known as the only Negro in the game probably puts me a hundred dollars a week ahead of the others in market value…. Every time I go out and beat one of the big ones, like Emerson, I can almost hear the cash register ringing up a higher figure…. People will usually pay a little more for a product that’s different–and that’s what I am.

By the time Ashe finished his Army service and elected to sign a pro contract, he was worth a lot more. He ultimately agreed to a deal worth $750,000 over five years.

He struggled more with the question of what non-monetary value his fame could offer. Some Black activists pressed him to become more vocal in the Civil Rights movement. At this stage of his career, he preferred to set an example and leave it at that.

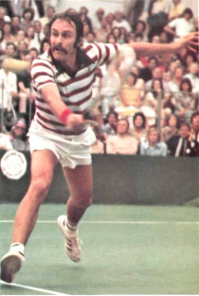

Ashe giving a clinic in 1968

Arthur was too intellectually curious to settle for easy answers. On a State Department tour of Africa in 1971, he told Frank Deford, “Before I’m finished in tennis, I want to get out and see everything, everything on earth.” Eventually, he accepted a more public role on racial and other issues, but he remained open-minded above all else.

* * *

Ashe never lost his reputation as an inconsistent player capable of soaring short-term feats. As late as 1974, John Newcombe explained how to handle one of Arthur’s hot streaks: “you’ve just got to demoralize him by raising your game a touch.”

By then, Ashe was in his thirties, widely considered to be on the downslope of his career. His shock victory at Wimbledon in 1975 changed all that. He tacked on another eight titles in the twelve months that followed, briefly earning a place at number two in the ATP rankings.

He never left the public eye. His retirement was accelerated by a heart attack in 1979. A blood transfusion during a second heart surgery is believed to be how he contracted HIV. Ashe was hyperactively busy throughout retirement, even as the disease left him with less and less energy.

The “supreme casualness” that defined Ashe on the tennis court could hardly account for the scope of his post-retirement activities. He had grown up hearing Arthur Sr. say that in a hundred years, no one will care what we did. At some point, Arthur Jr. must have realized his father was wrong.

A century from now, Arthur Ashe’s life will still matter, very much.