I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. If this is your favorite player, Congrats! (or: I’m sorry.)

* * *

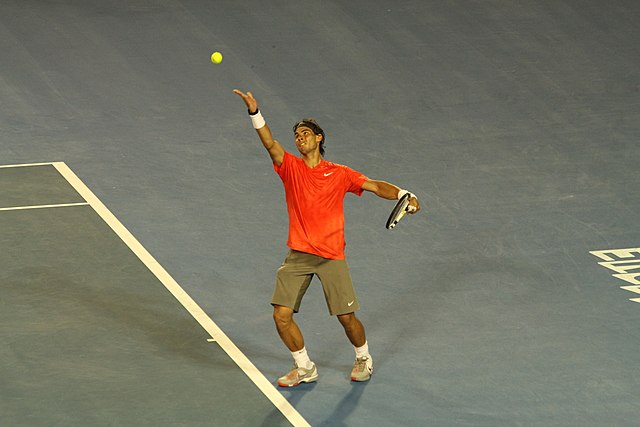

Rafael Nadal [ESP]Born: 3 June 1986

Career: 2003-present

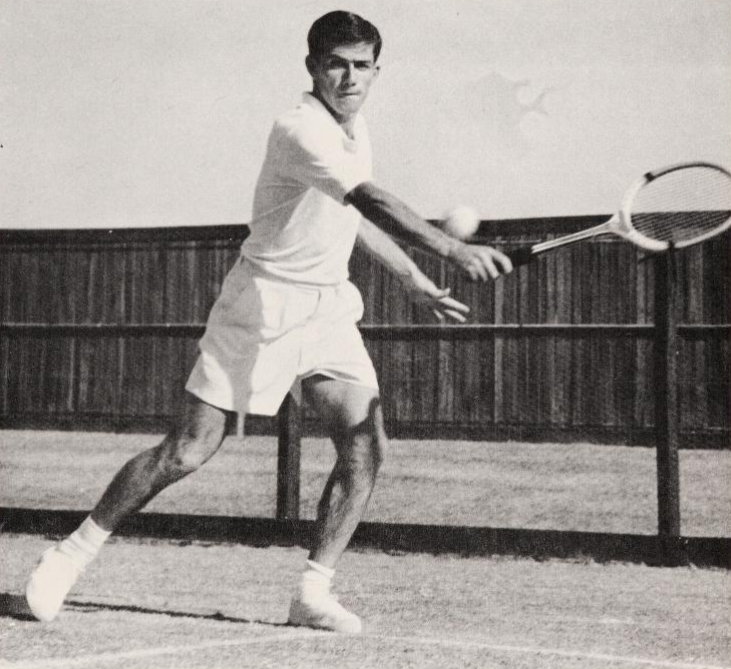

Plays: Left-handed (two-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (2008)

Peak Elo rating: 2,370 (1st place, 2009)

Major singles titles: 22

Total singles titles: 92

* * *

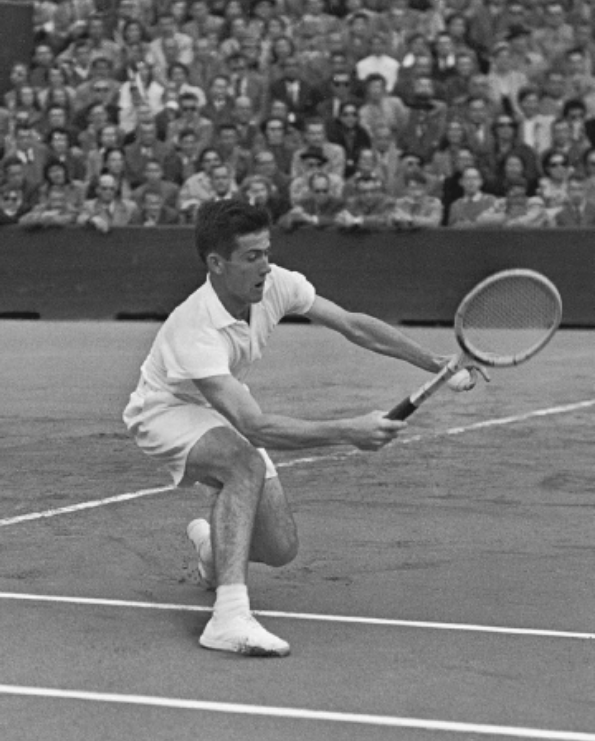

Break point on the Rafael Nadal serve is where dreams go to die.

You’ve worked so hard. Nadal’s serve is not the best in the game, but when you put it back in play, you’ve got a new set of problems to deal with. It’s the depth, the power, the topspin. Maybe you returned well for a few minutes; maybe you caught Rafa in a rare lapse. You reach break point.

Odds are, you’ve come this far by winning some points in the deuce court. Left-handers are, on average, better on the ad side. The opportunity to slice a wide serve to a righty’s backhand gives them about a three-percentage-point boost, a substantial difference next to the usual small margins in tennis. Nadal is no different. While he wins more service points in both courts than the average lefty, the three-point gap remains the same.

Now, at 30-40, or ad-out–you don’t think you got to 15-40 against Rafa, do you?–the pressure should be on him. He’s the one who scuffled himself into this position. He’s the one facing the loss of a service game. A big swing or two, and you could grab the break.

But no. The pressure is on you.

Nadal is going to hit that lefty slice to your backhand. (Actually, he goes to the wide corner with the first serve only about two-thirds of the time. You still have to lean in that direction.) He’s a tick more conservative facing break point, so he’ll probably land his first serve. You’ll be pulled off the court (or wrong-footed, if he goes down the tee), so you’ll start the rally at a disadvantage. Against a man who might be the greatest baseliner in the history of the game.

So you probably lose the point. You’ll be lucky to get another chance. Rafa holds almost half the games in which he faces a break point.

Oh, and if you somehow make that big swing and convert your opportunity? It won’t mean much if you can’t back it up. Fair warning: Nadal breaks serve in about one-third of his return games. If you’re trying to consolidate your edge at Roland Garros, you probably don’t even want to know your chances. Opponents there manage to hold barely half of their service games against him.

It’s not complicated, it’s just impossibly daunting. As Rafa explained in 2005, after winning his first of eleven titles in Monte Carlo: “I don’t miss a lot of balls.”

* * *

Most tour players serve better when facing a break point. Unlike tiebreak jitters, which give the edge to the returner, break point pressure adds up to a edge for the server. Most men land a few more first serves, make fewer errors, and save break points at a slightly higher rate than they win lower-pressure points against the same opponents.

The King of Clay just does it better than almost everyone else.

For a dramatic example, look no further than the 2007 French Open final. Roger Federer earned 17 break points, ten of them in the first set alone. Nadal denied each one of those first ten, as well as six of the seven that followed. Federer, overeager to convert, whacked seven unforced errors on those 17 points. Perhaps most telling of all, Rafa gradually shut down the opportunities altogether. After Roger went missed 15 of 16 chances in the first two sets, he generated just one more opening in the two sets that followed.

The Spaniard did it again a year later. In the 2008 Wimbledon clash that has come to define the Roger-Rafa rivalry, Federer earned 13 break chances. Nadal allowed him to convert just one, in the second set. (On break point, Rafa not only served down the tee, he approached to Fed’s forehand. Gotta say he deserved that one.) No matter: Nadal managed to break twice in the same set. A few hours later, he broke again for the 6-4, 6-4, 6-7, 6-7, 9-7 victory that no tennis fan will ever forget.

Rafa wasn’t always that good facing break point, against Federer or anyone else. When we crunch the numbers, though, we find that he has spent most of his career at the top of the leaderboard for this arcane but crucial statistic.

I went through every tour-level match since 2003 and compared each player’s performance on break points to his results on other service points. If he won 70% of non-break point serves, for example, a naive forecast would suggest that he saved 70% of the break points he faced. In fact, the average player upped their game enough to win between 71% and 72% of those points.

For 6,400 break points faced, Nadal has maintained double that advantage. In a match where he wins 70% of service points, he doesn’t edge up to 72% under pressure, he jumps to 74%. In his most clutch seasons by this measure, he is almost twice as good as that. He has been remarkably consistent, as well. His edge when facing break point has exceeded tour average for 18 of his 20 tour-level seasons.

Another way to put it: Rafa has saved approximately 233 break points simply by playing better in those moments than he does the rest of the time. That’s about six months’ worth of hard-earned break points, erased. No 21st-century player has saved more. The only man who comes close is another Spanish lefty, Feliciano López, with 218. Nadal’s only contemporaries* who improve their game by a larger percentage margin are López and John Isner.

* Incidentally, the turn-of-the-century player who saved the most break points by raising his game was Nadal’s current coach, Carlos Moyá.

Asked to explain what was going through his head during the 2008 Wimbledon final, Rafa said, “[I] just focus in every point.” Some points a bit more than others, apparently.

* * *

So: about 6,400 break points faced, more than 4,200 of them saved. Over 11,000 career break points generated, about 5,000 converted. Pick a category, just about any category, and the numbers boggle the mind. Especially when clay courts are involved.

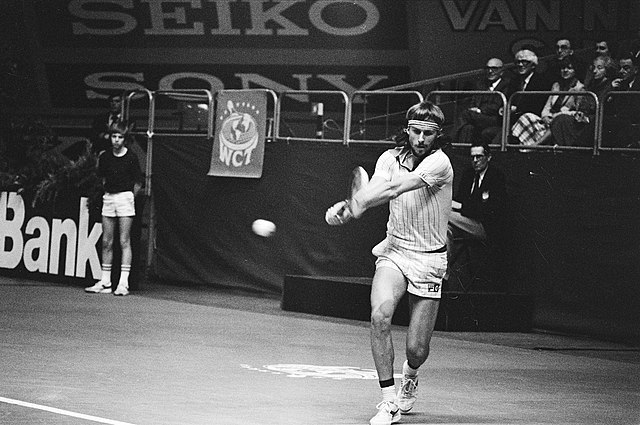

No player ever justified a nickname like Rafa has proven ownership of “The King of Clay.” There was dirtballing royalty before Nadal came along–when Rafa first picked up a racket, Björn Borg’s French Open records looked like they would stand forever. In 2004, if you said “King of Clay,” people would think you were talking about Guillermo Coria. Now, with 14 Roland Garros titles and counting, Nadal will remain the sovereign of the surface for however long humans play tennis.

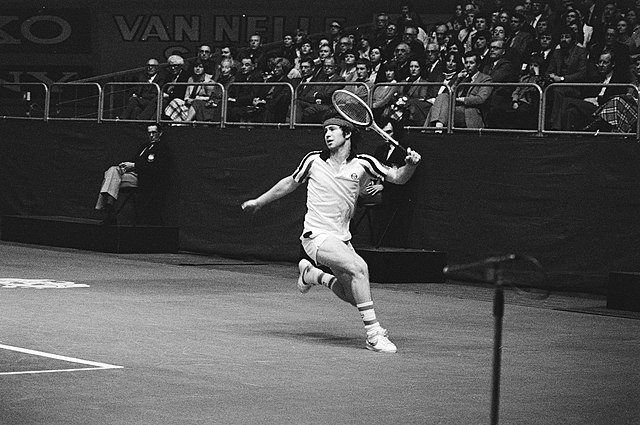

Coria was still a prime contender when he lost to Nadal at the 2005 Monte Carlo Masters. Three weeks later, the two men met in the Rome final, as well. Coria pushed the 18-year-old to 6-all in a fifth-set tiebreak but still came up short. When they met again at Monte Carlo in 2006, the balance of power had shifted for good. Rafa crushed the Argentinian, 6-2, 6-1.

The Spaniard’s Monte Carlo run in 2005 kicked off a clay-court winning streak that would last more than three years. Nadal won 81 straight matches–including three Monte Carlos, three Barcelonas, three Italians, and two French Opens, not to mention five defeats of the world number one–before Federer finally got the better of him at the 2007 German Open. Of course, he bounced back to win the French. Nadal lost only a single decision on clay in 2008, as well.

You will not be surprised to learn that 81 matches is the longest single-surface win streak in Open era men’s tennis. Rafa also holds the record for most consecutive sets won on a single surface. That mark stands at 50, and the most frequent set score of the bunch was 6-1.

Here’s the truly impressive thing about the two unbeaten runs: The set streak began more than ten years after the match streak ended.

Nadal’s longevity is where we hit the really incomprehensible numbers. He recently recorded his 900th consecutive week in the top ten. He’s up to nearly 600 weeks in the top two. He has more clay-court match wins–474–than any other player in the last four decades, yet his losses are so rare that the Wikipedia page summarizing his career statistics lists them all.

* * *

None of this should minimize Rafa’s exploits on other surfaces, or the fact that he has modified his game to beat the best players in the world on hard and grass courts. Even before he beefed up his serve and adopted more aggressive tactics, he could deprive Federer of hard-court titles that, in those early days, felt like his birthright.

Nadal’s adaptability is probably his most underrated quality. He won a doubles gold medal on hard courts, for crying out loud. Entering doubles events only occasionally, he has racked up eleven career titles. My Elo ratings suggest that he has ranked among the best doubles players on tour throughout his career. On the singles court, he wins three-quarters of his net points.

Still, it will always come back to the clay. In tennis, especially in the modern era, everybody loses sometimes. The exceptions to that rule are so rare that we can usually just ignore them. But not with Rafa. His record at Roland Garros–or Monte Carlo, or Barcelona–is nearly perfect.

This presents a problem for rating systems. When you win 81 clay-court matches in a row, or 14 French Opens in 18 tries, you aren’t promoted to some higher level with a more appropriate level of competition. There’s nowhere else to go. There’s nothing to do but keep winning.

But what if there were a way to crank up the difficulty level, like a chess app that can always play just a little bit smarter? Five years ago, I tried to simulate that within the framework of tennis Elo ratings. Instead of looking at a player’s rating after a long winning streak, I asked a different question. How good would a hypothetical player have to be in order to win so much in such a short span? They sound like similar questions, but there is a subtle difference. The first version establishes the minimum level a player would need to attain to accomplish a particular feat. The alternative approach tries to determine how good he would need to be to make such an outcome likely.

And let’s face it, few things in tennis have ever seemed more likely than Rafa winning another French Open title.

I won’t go through all the details here–you can read my earlier article if you’re interested. In May 2018, Nadal’s records at Monte Carlo and Roland Garros rated as the best single-tournament performances of the Open era, ahead of nominally comparable exploits like Borg at the French and Federer at Wimbledon, Halle, or Basel.

You probably aren’t surprised that Nadal tops the list. I wasn’t, either. But the exact numbers are staggering. Rafa’s peak Elo–in the traditional calculation–is 2,370. That’s good for sixth of all time. The highest peak of the Open era is Borg’s, at 2,473.

Nadal’s performance in his first 14 Monte Carlos rated more than one hundred points above Borg’s peak, at 2,595. His French Open record up to that point (excluding his injury withdrawal in 2016) works out to exactly the same figure.

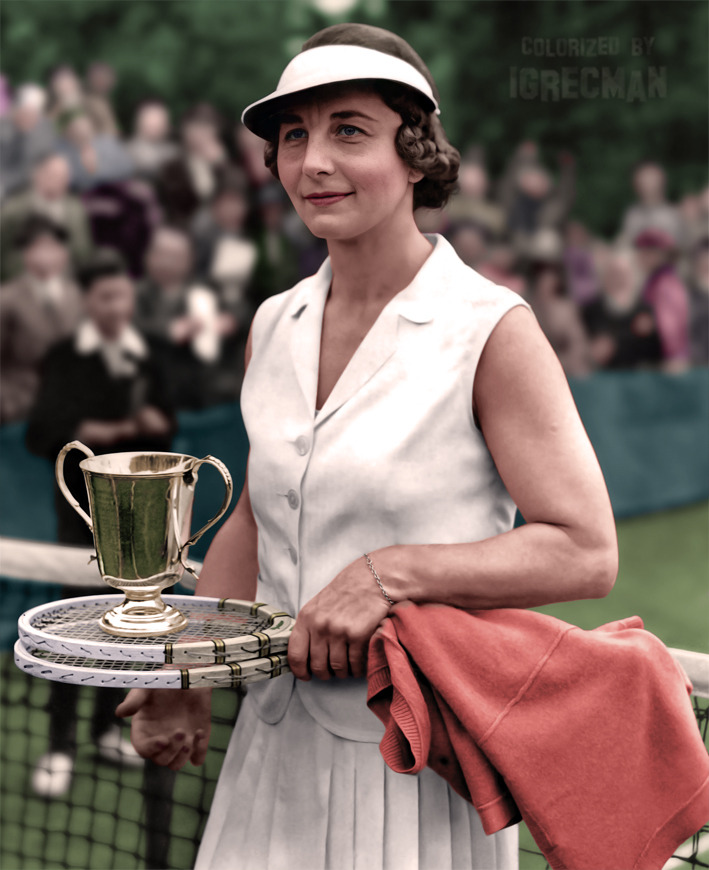

Run the same numbers now, and Nadal’s 14 titles in Paris continue to merit a rating just shy of 2,600. You have to go back to Suzanne Lenglen to find anything like it, and even setting aside the million reasons you can’t compare the two, Lenglen sustained her level for less than half as long.

In a world where all tennis was played on clay, Rafa would be the best of all time. Heck, even at 50%, the extra time on dirt would’ve been enough to close the gap. He certainly deserved a few chances to play–and, presumably, dominate–a year-end Tour Finals on his preferred surface.

As it is, he’ll have to settle for his undisputed position as the King of Clay. In the last 20 years, the Big Three have raised the standard for what it takes to rank as an all-time great. Nadal, even more than his famous rivals, has set records that will never be broken.

* * *

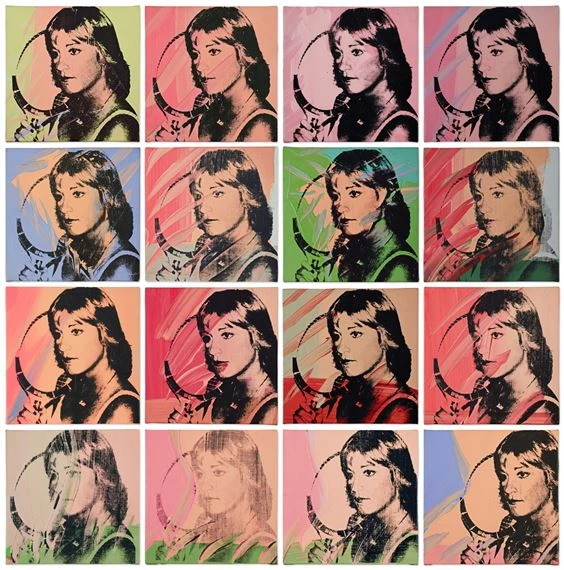

Previous: No. 9, Chris Evert

Next: No. 7, Bill Tilden

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: