Previous: February

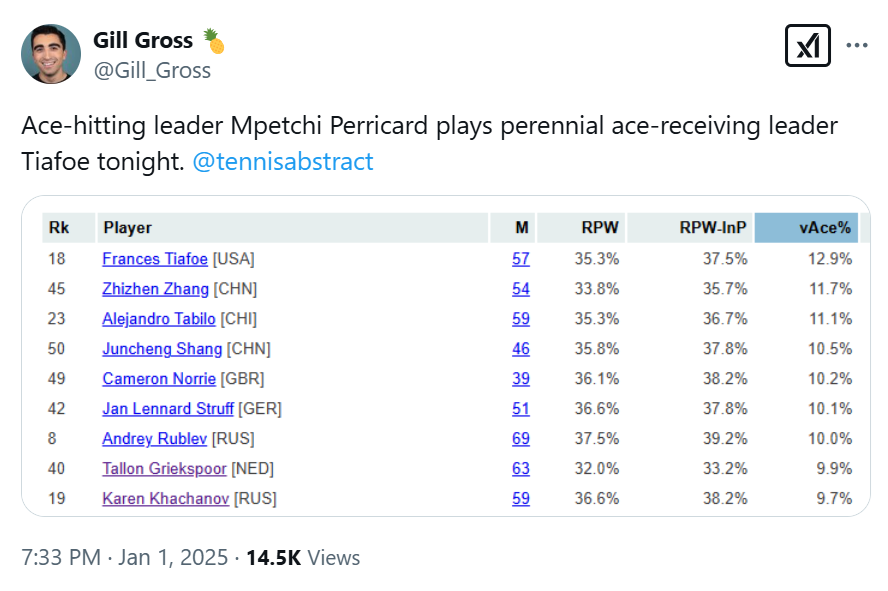

Off we go…

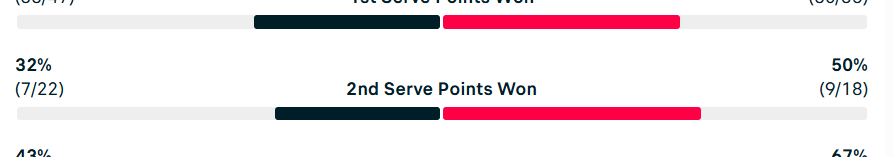

1. One of the Miami quarter-finals pitted two guys who I have recently highlighted as having weak still-developing second serves, Arthur Fils and Jakub Mensik. Mensik advanced, yet neither one showed much progress in that problematic category:

For Mensik, 50% isn’t bad.

2. Electronic Line Calling (ELC) is here, and it is quickly spreading to the lower levels of tennis. Colette updates us on the status of ELC in college tennis, where players previously called their own lines.

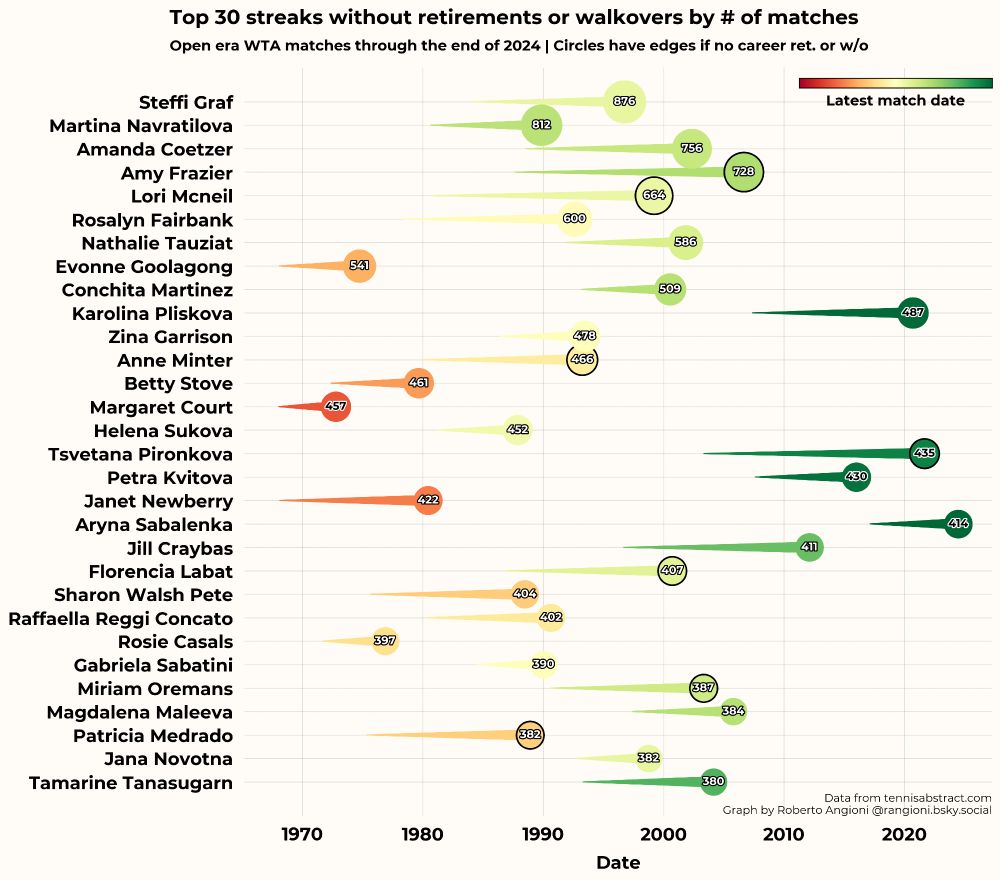

3. Roberto made a nice graphic of the longest non-retirement streaks in WTA history:

There’s a men’s version, too.

4. RIP Yola Ramirez, the greatest Mexican tennis player in history. She was twice a French Open finalist and picked up two doubles major crowns.

My records, which are not 100% complete, give her a career singles record of 376-144, spanning the era from 1951 to 1972. She amassed at least 51 career titles, almost all on clay. In five of them, she defeated women who made my Tennis 128 list: Maria Bueno, Darlene Hard, Ann Jones, and Nancy Richey.

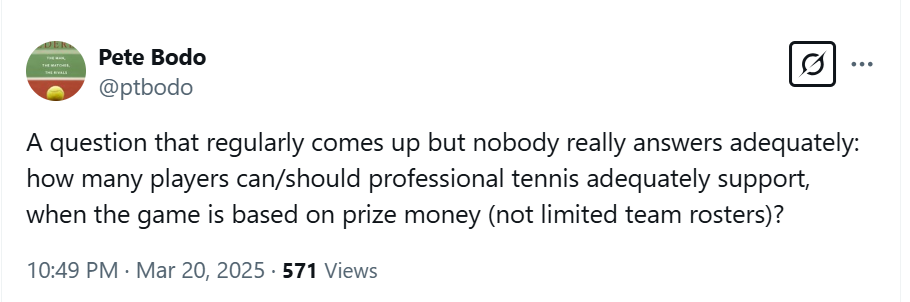

5. The PTPA filed a lawsuit against various tennis bodies, and it raised the usual crop of questions and takes about tennis finances. I appreciate Pete Bodo for framing at least part of it so clearly:

Tennis has sometimes tried to manage the number of players considered to be pros, for instance by limiting the number of tournaments/round that grant ranking points. But as Pete hints, that isn’t the issue. If there’s a pot of gold for top players, there will be an endless supply of aspirants, whether those aspirants are globetrotting juniors, college players, ITF warriors, or Challenger tour regulars. Enough people out there have federation or family support that they can chase their dreams without earning anything like a living wage (or in some cases, anything at all).

In practice, the answer is “the number of players who make grand slam qualifying cuts.” But even that is too vague, because players don’t necessarily stay at that threshold for long. All this is to say: People who lobby for a different financial structure should start with these questions. How many players should earn a living wage from tennis? And then, what changes would be necessary to make that happen?

5. Patrick Ding writes about women’s tennis like no one else does, often covering players you haven’t heard of. Here he is on the scheduling decisions of Tereza Valentova.

6. There’s a tennis element in the new BBC series, Towards Zero, based on an Agatha Christie novel. Simon Briggs looks into the true story behind the fiction:

On the tennis court, Strange and Goold were each renowned for their “killer” backhands – a detail which becomes a key plot point in the book. And if Christie has transposed the drama from the French Riviera to the English one, that is probably because of her own upbringing in Torquay.

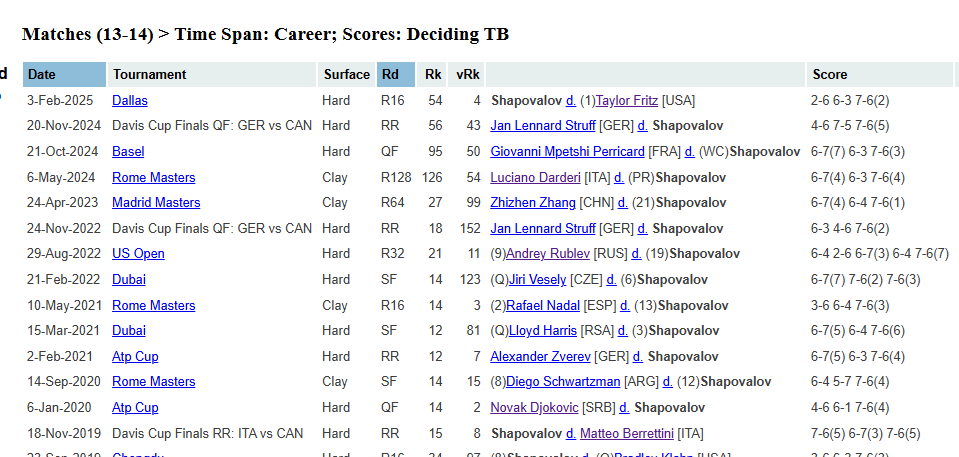

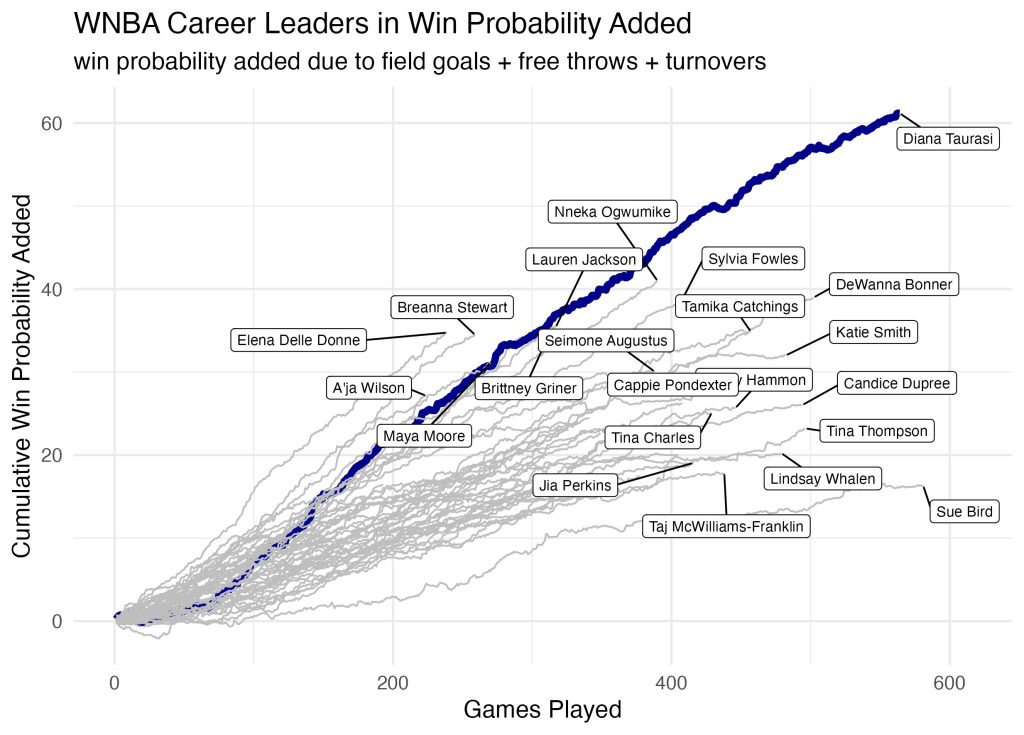

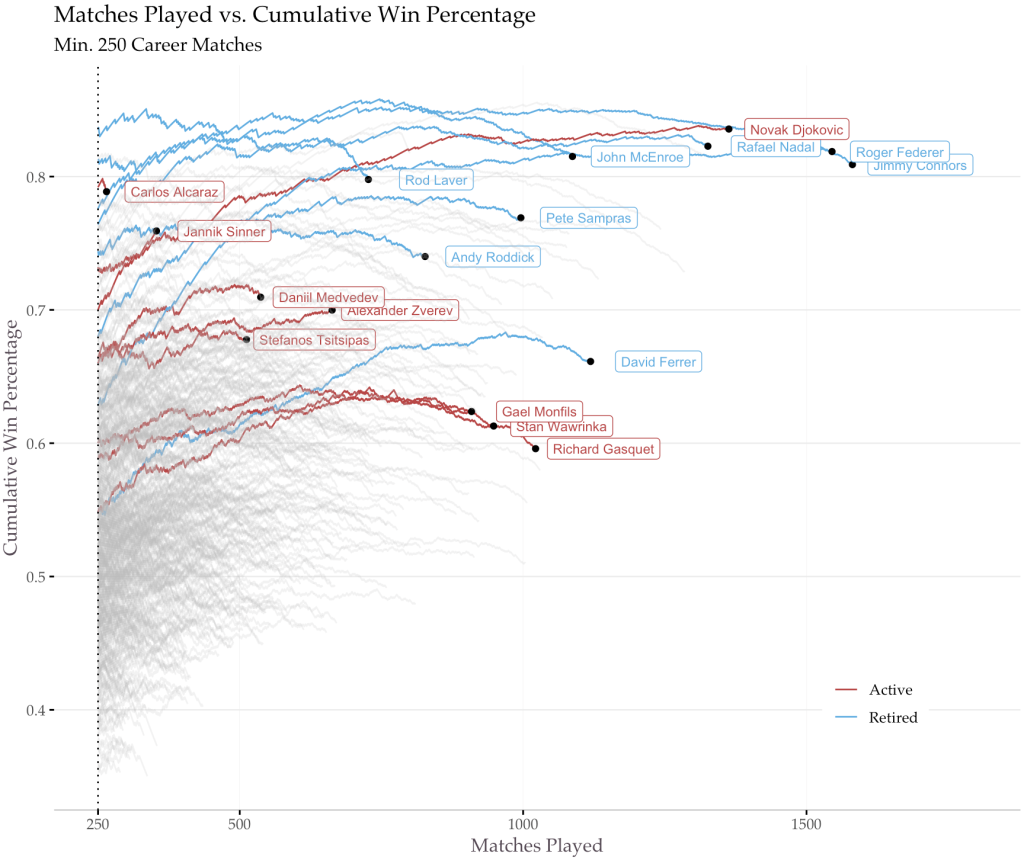

7. Ben Marrow built a tennis twist on a basketball dataviz I included in last month’s roundup:

He also made a slick interactive version.

8. If you’re not reading Andrea Petkovic, well … maybe this, about Monica Niculescu will finally get you started?

She was an immensely talented player who did everything she could to mess with your technique and I’m not afraid to admit that it worked. I got my revenge once we were older and I was taller and stronger and didn’t have a complete meltdown every time she hit a slice. But the panic reared its ugly head until the very end of my tennis player’s days whenever I saw Moni Niculescu near me in the draw. Some things fade, some things are forgotten but Monica Niculescu remains forever.

Great stuff about Aga Radwanska and others in the same article.

9. Alison Riske is up and running on Substack, too. Her first update is about all things Charleston.

10. RIP Juan Aguilera, 1990 Hamburg champion. He peaked at #7 in the world, scored seven top-ten wins, and never made the trip to Australia.

11. This month’s match video is the 2004 US Open third-rounder between Venus Williams and Chanda Rubin:

Venus wasn’t playing her best tennis–she lost in the next round to Lindsay Davenport–but it was a good effort from Chanda nonetheless. I happened to see one of Rubin’s earlier-round matches that year on a side court. All I remember is one of the few other fans, with a thick Caribbean accent, incessantly shouting “Go Chanda!”

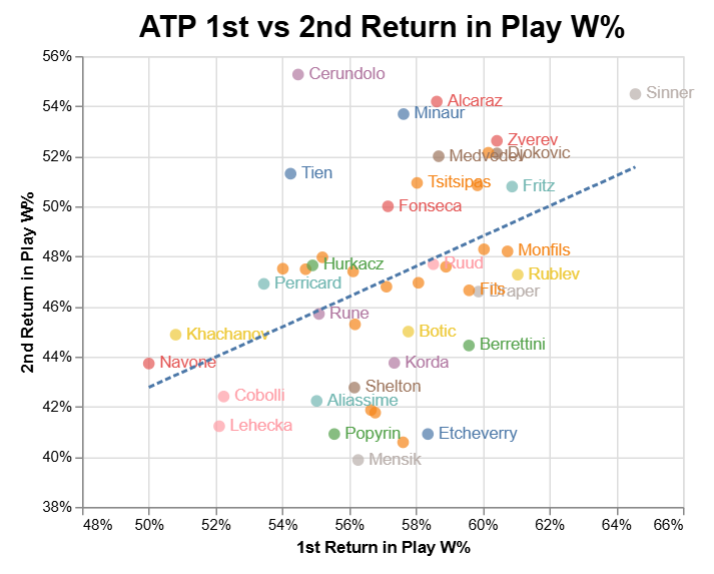

12. I almost scratched this monthly roundup so I could write about Francisco Cerundolo today instead. I can’t stop thinking about his position on this graph from my Mensik post:

Cerundolo is even more of an outlier than Mensik, just in the opposite direction. He’s a bit below average in putting first serves away when the return comes back, but he’s better at converted in-play second serves than anyone else on tour.

This isn’t exactly the same as second-serve winning percentage, but it’s closely related. The Argentinian blew everybody away in the more standard category in Miami:

The streak lasted even a bit longer: Cerundolo won 70% of second-serve points in the first set of his quarter-final against Grigor Dimitrov. Alas, he finally came back to earth–37% in the final two sets–though he nearly won the match anyway. If he can keep this up away from the South American Slam, it will merit a longer treatment.

13. Here’s some new (in English) research into the Sumarokov-Elstons, the first family of pre-Soviet Russian tennis.

14. One more that we lost this month: RIP John Feinstein. He was better known as a golf and basketball writer, but he covered tennis as well, including the 1991 book Hard Courts. Pete Bodo wrote a nice remembrance, and I enjoyed this thread from a colleague.

15. Now that Alexandra Eala has ignited tennis mania in the Philippines, how long until we get a WTA event in Manila? There has been some tennis in the islands for more than 100 years, and competitive women’s tennis back to at least 1935. Eala is surely the best from the country so far, though I did notice that early champ Minda Ochoa upset visiting American Helen Marlowe–a two-time national junior finalist–in 1936.

16. Forgot this one last month: In her WTA debut in Austin, Malaika Rapolu got called for a time violation on return. I know it’s not unprecedented, but it’s rare enough to be a harsh welcome to the tour. Now, umpires just need to apply the same standards to players inside the top 500.

17. Tennis execs are surely paying attention to the TGL, an indoor, team-based, simulator-driven golf tournament that just wrapped up. With an eleven-week season, it requires more buy-in than any tennis upstart is going to get; in that sense, it more closely resembles 1970s-era World Team Tennis. The high-tech approach seems to have worked, deviating from the traditional version of the sport more than any tennis exhibition ever has.

18. One more non-tennis note: I recently read James Astill’s The Great Tamasha, about Indian cricket from its beginnings to the (then–the book was published in 2014) new Indian Premier League. Another example of a sport ramping up fan engagement and shortening formats, and succeeding.

This, though, is what will stick with me:

[Bengali sociologist Ashis] Nandy shook his head. ‘I don’t see much of cricket in this IPL business. It is simply a degraded form of the game. What is the point of it? Is it an effort to catch up with other sports? Why? So many sports are so similar. Why can they not allow us to have one game to be different?’ He paused, and gazed into space. He looked bereft.

19. Someone complained about the lack of music last month, so here ya go:

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: