Is Sofia Kenin back? Was she ever gone? Was she ever there in the first place? Has any player so persistently defied categorization?

Big questions aside, Kenin is suddenly more relevant than she has been in at least 18 months. This time last year, she was suffering through a nine-match losing streak. She would add another bad patch in the summer and fall out of the top 150 before reaching last October’s Tokyo final. Since then, she has lost only one first-round match (when she drew Coco Gauff in Melbourne) and made another 500-level final in Charleston. Kenin had set point on Sunday to force Jessica Pegula into a third set before the veteran summoned her mysterious forces and finished the job.

This is all a far cry from 2020, when the American bracketed the pandemic pause by winning the Australian Open and reaching the French final. But her Charleston showing moves her ranking back up to 34, the highest it has been since late 2023. Her Elo rating is even better, good for 25th on tour.

What is working again for Sonya? Is she back in the top 40 to stay?

Oh, those groundstrokes

When the Kenin game is clicking, it is a joy to watch. She is one of the most versatile players on tour, with the ability and willingness to deploy just about every shot in the book. She tried ten drop shots in the Charleston final against Pegula and sent both forehand and backhand slices across the net. I’ve even seen her win points with moonballs.

In the 2020s WTA, though, versatility can only be the icing, not the cake. Fortunately for the 26-year-old, both her forehand and backhand are among the game’s best. By my Forehand Potency (FHP) metric, she ranks 16th on tour over the last 52 weeks, in between the fearsome weapons of Iga Swiatek and Amanda Anisimova. Her backhand is the signature shot, and it rates even better, coming in 9th.

Combined, she gets more value from her groundstrokes than almost anyone else. Here is the top ten, based on charted matches since this time last year:

Player FHP/100 BHP/100 Combined Jelena Ostapenko 18.7 11.0 29.7 Amanda Anisimova 9.2 14.1 23.3 Aryna Sabalenka 13.0 9.3 22.3 Ekaterina Alexandrova 13.6 8.5 22.1 Danielle Collins 12.7 9.0 21.7 Linda Noskova 14.1 7.4 21.5 Iga Swiatek 10.0 9.0 19.0 Madison Keys 11.3 7.5 18.8 Sofia Kenin 9.4 7.8 17.2 Jessica Pegula 8.3 8.0 16.3

For all the heavy hitters on that list, Kenin is more like Pegula than the rest. She attempts to dictate with placement, not power. Give her an opening, and she’ll rarely squander it. She’ll miss as much as some of these sluggers, but that’s because she relentlessly aims for the lines. The overall tally tilts in her favor.

She falters when she doesn’t have enough space to work with. Pegula, boasting perhaps the best anticipation of anyone on tour, consistently cut down the angles Kenin had to work with on Sunday. Sonya doesn’t have the patience to wait for the next opportunity, so she aimed for narrower and narrower spaces. The result, predictably, was a giant pile of unforced errors. She committed 33 of them off the ground–nearly one in four points.

Speaking of patience: That’s one category where she resembles the power hitters on that last list. Her average point in the past year has averaged just 3.4 shots, the same as Madison Keys and Ekaterina Alexandrova, fewer than Clara Tauson or Donna Vekic. A bit of a paradox is emerging here: Kenin has an impressive range of all-court and defensive skills, but she doesn’t play like it.

Is she a… servebot?

The American doesn’t seem like a weak returner. Aggressive, yes. Too aggressive, maybe. But any woman with such an effective backhand should be able to post decent numbers against the serve.

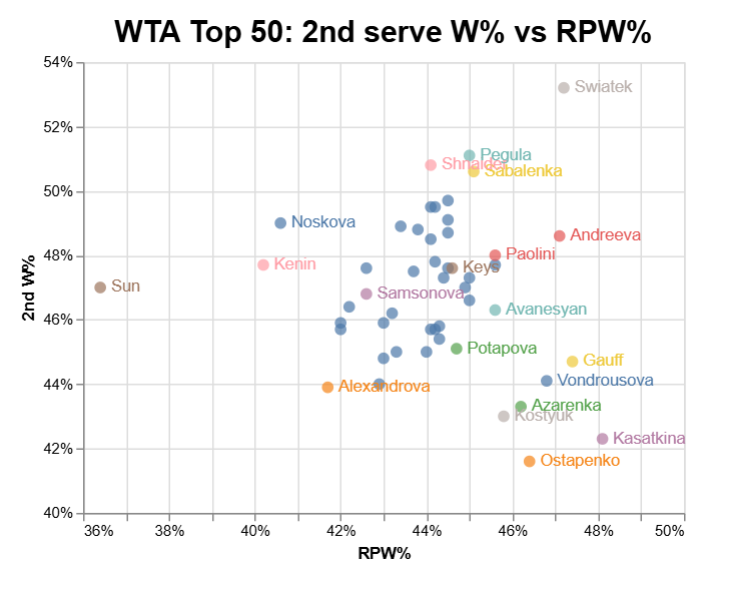

Yet: It is a constant struggle to break serve. The typical player in the WTA top 50 breaks 37% of the time. Swiatek grades out at 45.5%, and several more women top 42%. Pegula stands at 38.5%. Kenin, at 30.3%, ranks 48th of 50. Here are her peers at the wrong end of the list:

Player Break% Lulu Sun 19.7% Linda Noskova 28.4% Sofia Kenin 30.3% Katie Boulter 30.8% Clara Tauson 31.2% Magda Linette 31.5% Xin Yu Wang 32.0% Donna Vekic 32.6% Ekaterina Alexandrova 32.9% Barbora Krejcikova 33.1%

Judging by some of these names, Kenin might be able to sneak into the top 20 with this return game. Vekic is 20th on the WTA points table. Tauson is 21st.

If there’s one characteristic that ties many of these players together, it is that their results run hot and cold. Krejcikova has won two slams but often struggled to get past early rounds. Noskova is a nightmare for Iga but manageable for others. Low break rates mean that the margins will always be narrow: Good for upsets and the occasional hot streak, bad for any semblance of consistency.

Kenin essentially takes the racket out of her own hands. Of players with at least ten matches in the charting database over the last year, only Danielle Collins puts fewer returns in play:

Player RiP% RiP W% Danielle Collins 61.9% 55.7% Sofia Kenin 62.5% 54.0% Ekaterina Alexandrova 63.2% 58.3% Amanda Anisimova 64.3% 58.9% Alycia Parks 65.9% 59.6% Linda Noskova 66.4% 53.9% Liudmila Samsonova 66.9% 56.6% Barbora Krejcikova 67.3% 53.9% Bianca Andreescu 67.4% 54.4% Madison Keys 68.1% 57.6%

A lot of these names are starting to look familiar. As with the FHP/BHP lists, Kenin shares space with some of the game’s biggest hitters, even if I wouldn’t think of her that way. Maybe she disagrees: She certainly takes chances on return as if she does.

Yet the results aren’t there. The rightmost column, winning percentage on returns in play, shows that Kenin trails Collins, Alexandrova, Anisimova, and most of the rest by a healthy margin. She is roughly equal to Noskova and Krejcikova, though the Czechs get more balls back to start with. It’s fine to win 54% of points if the denominator is big enough–to take one example of many, Paula Badosa stands at 52%–but Sonya loses too many points without forcing the server to hit even one more ball.

As for the question in my subhead: No, Kenin isn’t really a servebot. Her serve itself ranks in the middle of the pack. But alas, her return stats are better suited to someone with a much more powerful first strike.

Same as the old Kenin?

It is tempting to conclude that Sonya’s 2020 was a remarkable streak of luck. She won the Australian Open after sneaking past Ashleigh Barty in the semi-final, winning fewer than 51% of points. She picked up the Lyon title a month later with four three-setters and five tiebreaks. She reached the Covid Roland Garros final even though Samsonova won more points than she did in their first-round encounter.

On the other hand, Kenin is a fundamentally different player than she was five years ago. One indicator is her now-languishing break rate:

Year Break% 2018 34.0% 2019 34.0% 2020 34.7% 2021 33.9% 2022 23.3% 2023 31.5% 2024 28.3% 2025 30.9%

34% or 35% isn’t great, but it’s worlds apart from where she is now. Rybakina, while off her own peak lately, gets by with just 36%.

Back then, the American wasn’t so quick to pull the trigger. Based on the 17 matches we have in the charting database, her average point in 2020 lasted 4.1 strokes, another sharp contrast to her 3.4 of the last 52 weeks. 4.1 is at or above tour average, equal to Coco Gauff’s usual mark.

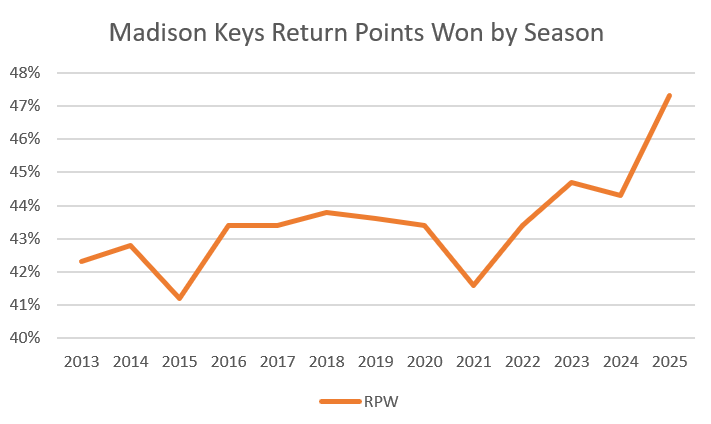

A big part of the difference is that she put more returns in play. In those 2020 matches, she got 71.7% of serves back, nearly ten percentage points higher than her current rate. She also won more of those points:

Span RiP% RiP W% 2020 71.7% 55.0% Last 52 62.5% 54.0%

By just about every metric I have, Kenin is more aggressive now than she was at her best, and the strategy isn’t paying off. Perhaps she feels that she has to hit harder–or at least adopt tactics that mimic her more powerful peers–to keep up. Maybe she has lost a bit of quickness: Ankle and foot injuries sidelined her for much of 2022.

2020-era Sonya, then, is not back. Her form over the last six months suggests she might have landed on something that will work, if not anywhere near her peak level. The stats keep telling us she’s just like Alexandrova, and the risk-taking Russian has spent years in the top 30, picking up a title every year or so and making trouble for her higher-ranked peers. Kenin is on track to do the same.

Yet unlike Alexandrova, Anisimova, and the rest, Kenin is a former slam champ, with memories of an entirely different level of tennis. Performances like Tokyo and Charleston suggest she is getting closer to recapturing that magic. If she starts getting more serves back, then it’s time for the rest of the tour to worry.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: