Joao Fonseca made easy work of last week’s Next Gen Finals. He went undefeated against the world’s best under-21s, dropping just one set in best-of-five semi-finals and finals. The youngest player in the field, he joins Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz as 18-year-old champions in the seven-year history of the event.

There’s no secret to Fonseca’s success. He already possesses a devastating forehand, a shot with power that invites comparisons to fellow South Americans Juan Martin del Potro and Fernando Gonzalez. Outrageous as it sounds, Fonseca’s might turn out to be even better. The Brazilian has a more compact stroke, making his forehand more flexible–and perhaps ultimately more reliable–than the long-levered Delpo motion.

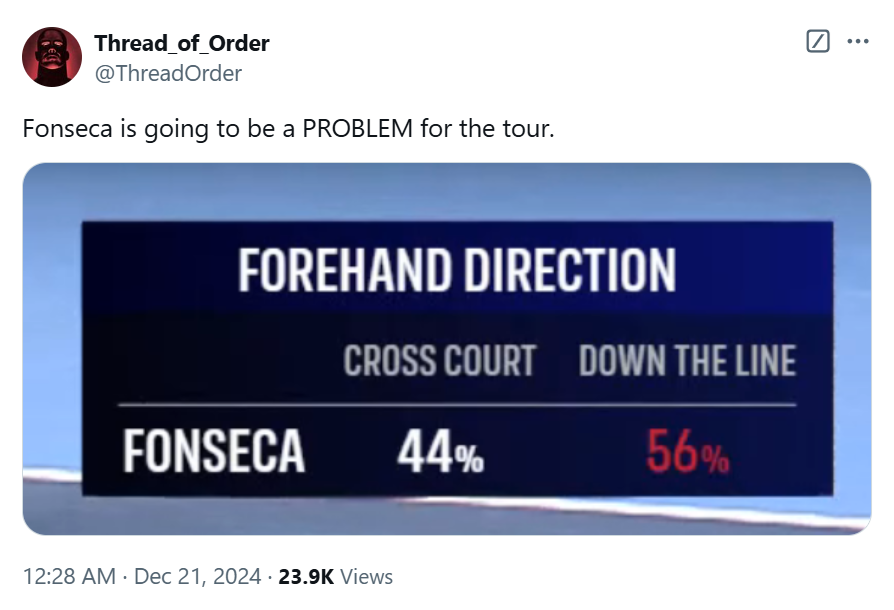

In his round-robin match against Jakub Mensik, the TennisTV broadcast flashed a stat meant to indicate one way Fonseca excels:

The TennisTV commentators were flabbergasted by these numbers: They’d never seen anything like it. Hugh, responsible for the screenshot here, got straight to the point. If a player with a forehand like Fonseca’s can consistently send the ball to his opponent’s weaker side, it’s game over.

The easiest direction to hit a groundstroke is back the way it came. That’s how we end up with protracted cross-court rallies. It takes impeccable timing to react to a elite-level cross-court forehand and change direction. (Pros drill that specific sequence, but no amount of practice makes it easy.) Down-the-line shots are doubly difficult because the net is higher as it nears the posts. The timing needs to be near-perfect, and there’s a smaller margin for error.

Here’s another way to get a sense of the dangerous risk level of down-the-line groundstrokes. Novak Djokovic, king of the down-the-line backhand, doesn’t hit that many of them. The inherent limitations of tennis rackets and the dimensions of the court are unforgiving. Fonseca, if he can really hit more than half of his forehands down the line, could defy those limitations.

Fact-check

Normally, I’d give you all sorts of numbers to help anchor Fonseca’s stats. How much does his 56% clip exceed tour average, or compare to someone like Sinner? That’s my goal, but first, we need to get into the weeds a bit.

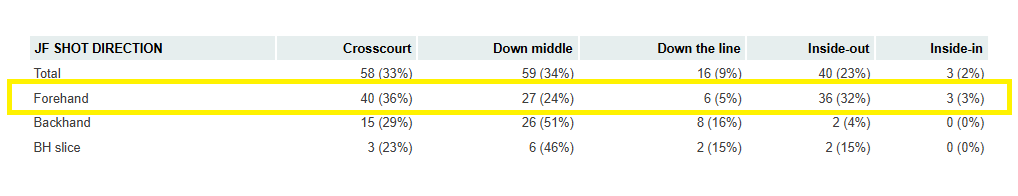

The Match Charting Project has 14 Fonseca matches in the database, including all five of his NextGen Finals contests. Here’s the breakdown of groundstroke direction for the Mensik match:

This is… not the same as the broadcast graphic. We should expect minor differences, both because the 44/56 stat was shown midway through the match, and because reasonable people can disagree about how to classify shots that don’t obviously belong to a specific category. But that’s not what’s going on here. There’s virtually no way to take these numbers and conclude that Fonseca hit more than half of his forehands down the line.

What’s more, Fonseca’s forehand-direction profile is rather pedestrian. That’s not to say that his forehand is ordinary, just that he aims in the same directions as his peers. Here is Joao’s forehand-direction distribution, based on those 14 charted matches, compared with tour average:

DIRECTION Fonseca Average Cross-court 40% 39% Middle 20% 22% Down the line 10% 11% Inside-out 26% 24% Inside-in 4% 4%

Ho-hum, right? Maybe he hits a few more inside-out forehands instead of going back up the middle. Even there, the two-percentage-point gaps between Fonseca and tour average could be an artifact of the matches we’ve charted. The Brazilian’s forehand does plenty of damage, but as a function of how he hits it, not where.

More weeds, sorry

I should probably let the discrepancy go, but let’s give it another minute. I don’t think the broadcast graphic was wrong, but it’s clearly measuring something different than what I count for the Match Charting Project stats. Maybe there’s some important subset of forehands that Fonseca is unusually likely to hit down the line?

One of the more difficult–and damaging–specific shots is the forehand down the line from the forehand corner. The MCP divides the court into three sectors by width: to the (right-hander’s) forehand corner, down the middle, and to the backhand. Maybe Fonseca particularly likes to change direction when he sees a ball in his own forehand corner?

A bit, but not by much. Here are the direction frequencies for Fonseca’s forehands from his forehand corner, for both the Mensik match and the average of his charted matches, along with the frequencies for his opponents:

To FH Middle DTL vs Mensik 58.1% 22.6% 19.4% Fonseca Avg 49.0% 23.6% 27.5% Opp Avg 45.7% 30.9% 23.4%

Nothing really dramatic here, and he went down the line less often in the Mensik match than his typical opponent does.

What about when Fonseca gets a ball down the middle? We saw in the MCP stats above that he hits a lot of inside-out forehands. That includes shots from the middle to the backhand side of a right-handed opponent. Here is the same group of frequencies for the same sets of matches, this time excluding left-handed opponents because they will naturally make different choices from the middle of the court:

To FH Middle DTL vs Mensik 29.7% 25.7% 44.6% Fonseca Avg 39.7% 20.0% 40.3% (RH) Opp Avg 34.2% 25.4% 40.4%

There’s a few more down-the-line shots in the Mensik match. But over 14 matches, Fonseca differs from his opponents only in hitting fewer balls back up the middle.

Maybe you’ve already worked out the underlying discrepancy. Since the 44/56 split adds up to 100%, there’s no “down the middle” category in the broadcast stats. The graphic splits forehands into two buckets, not three. That’s not how I think about tennis, and I suspect it’s not how you do, either. They would have done better to label the columns “to the forehand” and “to the backhand,” or something along those lines. It’s not unusual at all to hit 56% of one’s forehands to the opponent’s backhand side. But a lot of those “to the backhand” shots are not what anybody would normally call “down the line.”

The Fonseca difference

It’s not about tactics, it’s good old-fashioned power and precision. Fonseca’s forehand isn’t innovative, and it doesn’t need to be. If he hits his shots in more or less the same directions that his peers do, he’s probably doing something right. It means that at age 18, he has already internalized pro tactics. The difference is that he’s hitting those forehands harder, and he’s often landing them closer to the lines, something hinted at by his low rate of down-the-middle forehands.

He already shows up near the top of my Forehand Potency (FHP) leaderboard–though I’ll give you some caveats in a minute:

Rank Player FHP/100 1 Andrey Rublev 14.0 2 Jan-Lennard Struff 11.6 3 Joao Fonseca 11.3 4 Stefanos Tsitsipas 11.0 5 Carlos Alcaraz 10.8 6 Rinky Hijikata 9.7 7 Jannik Sinner 9.4 8 Casper Ruud 9.2 9 Juncheng Shang 8.6 10 Novak Djokovic 8.6

FHP combines forehand winners and errors, along with shots that lead to both opponent errors and winners on the player’s next shot. Given the vagaries of estimating the effect of one shot on others, Fonseca effectively sits in a tie for second place, as good or better than everyone except for Andrey Rublev. Which, I’d say, checks out.

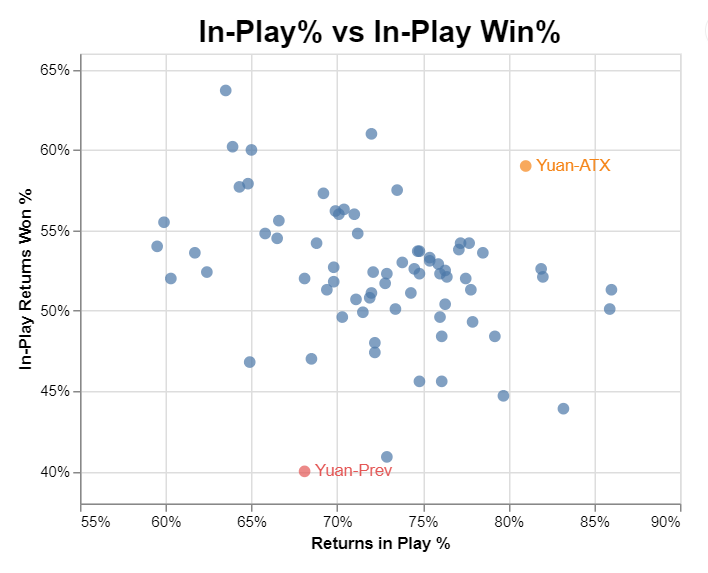

The caveats lie in the dataset. The Brazilian has faced only one top-20 opponent, and that was a possibly-unmotivated #20 Arthur Fils last week. The charting data on which FHP numbers are based includes all the NextGen Finals matches, along with some Challenger-level matches and some early rounds at ATPs. After all, he’s 18 and that’s all he’s played. Point being, an 11.3 FHP/100 (per 100 forehands) against that level of competition probably isn’t is good as Alcaraz’s 10.8 or Sinner’s 9.4, amassed against foes like each other.

But don’t take that adjustment too far. Fonseca scored a 11.0 against Fils in Rio, when he was barely 17 and a half. Facing Botic van de Zandschulp in a Davis Cup tilt, he registered a whopping 16.7 FHP/100. The Dutchman is hardly easy pickings: When Sinner played van de Zandschulp twice early in the season, he managed just 1.2 and 7.1 on the same metric.

Damage (not just) down the line

Fonseca doesn’t hit an unusual number of forehands down the line, but when he does, opponents barely stand a chance. Among the 200-plus players with as many down-the-line forehands in the MCP database as Fonseca has, he ranks sixth in points won when he hits the shot. Admittedly, it’s an odd list:

Rank Player W/FE% UFE% inPtsWon%

1 Juncheng Shang 33.6% 13.1% 66.4%

2 Nishesh Basavareddy 29.4% 10.3% 65.1%

3 Luca Van Assche 22.9% 11.0% 62.4%

4 Hyeon Chung 30.1% 19.9% 61.8%

5 Bjorn Borg 26.3% 7.3% 61.6%

6 Joao Fonseca 31.1% 17.6% 61.3%

7 Rafael Nadal 28.9% 12.8% 61.2%

8 Camilo Ugo Carabelli 10.3% 9.6% 60.9%

9 Corentin Moutet 29.4% 15.6% 60.6%

10 Zhizhen Zhang 22.8% 15.9% 60.3%

11 Guillermo Garcia Lopez 20.3% 5.9% 60.1%

12 Roberto Carballes Baena 10.1% 5.8% 59.7%

13 Carlos Alcaraz 26.7% 14.3% 59.7%

14 Grigor Dimitrov 23.8% 13.4% 59.3%

15 Juan Martin del Potro 26.8% 12.7% 59.2%

Average 20.1% 15.2% 53.4%

The 2024 Next Gen field is bizarrely well-represented, with Shang, Basavareddy, and Van Assche leading the way. Is this the age of the deadly down-the-line forehand? Some of the same caveats apply here as with the FHP list: The youngsters have played a different sort of opponent than Nadal, Alcaraz, or (!) Borg. The clay-courters on the list also make for awkward comaprisons. For dirtballers, the down-the-line forehand is a way to build points, not end them.

It’s clear that Fonseca loves this play. He ends points in his favor (with a winner or forced error) more than anyone on this list except for Shang.

Here’s the scary thing: A few clay-court matches are severely dragging down the Brazilian’s numbers. On hard courts, he moves up to second on the list, winning 68% of points in which he hits a down-the-line forehand. The shot ends points outright an incredible 48% of the time. Delpo’s numbers, though of course against stronger competition, pale in comparison, at 60% and 39%, respectively.

Some of the difference between Fonseca and the field is that his forehand is great, period. If you’ve got an extra ten miles per hour that the average player doesn’t, that’s going to show up in every direction, not just one. And for the most part, that’s what we see in Joao’s points won when hitting each category of forehand:

FH Pts Won Fonseca Tour Cross-court 58% 54% Middle 52% 46% Down the line 59% 53% Inside-out 57% 57% Inside-in 54% 59%

He’s better than average in all but the rarest of the five forehand directions. Even that isn’t really a negative: On hard courts he does better than tour average with the inside-in forehand.

The eye-catcher on that chart is 52% of points won when hitting a down-the-middle forehand. The typical player is likely to lose a point when hitting that shot. That’s not necessarily because down-the-middle forehands are bad, but because if you need to hit one, the point probably isn’t going your way. Unlike the other categories of forehands, it’s usually a defensive shot.

Of the 220-plus players with as many down-the-middle forehands as Fonseca in the MCP database, only 23 win more than half of those points. The Brazilian ranks fourth by points won when hitting down-the-middle forehands. It’s another oddball list, with Pablo Andujar, Tim Smyczek, Gilles Simon, and Carlos Berlocq rounding out the top five. (Yes, really.) To the extent we can group them together, those four men played a different brand of tennis, winning points with conservative shots as they wore down their opponents.

The more telling stat is that Fonseca actually ends points by clubbing forehands down the middle. The average player hits a winner or induces a forced error with less than 2% of these strokes. Joao comes in at 6.4%, better than anyone else in the dataset:

Rank Player W/FE% inPtsWon% 1 Joao Fonseca 6.4% 52.8% 2 Fernando Gonzalez 6.0% 43.2% 3 Christopher Eubanks 5.7% 38.8% 4 Thanasi Kokkinakis 5.0% 46.1% 5 Tomas Machac 4.9% 43.8% 6 Nicolas Jarry 4.7% 41.7% 7 Alexei Popyrin 4.4% 41.8% 8 Sam Querrey 4.3% 41.8% 9 Max Purcell 4.0% 38.5% 10 Lorenzo Sonego 3.9% 46.0% 11 Matteo Arnaldi 3.8% 49.5% 12 Lucas Pouille 3.4% 42.9% 13 Jan-Lennard Struff 3.3% 45.6% 14 Matteo Berrettini 3.3% 42.1% 15 John McEnroe 3.3% 44.0% 16 Otto Virtanen 3.2% 35.8% 17 Boris Becker 3.2% 44.1% 18 Nick Kyrgios 3.2% 43.2% 19 Roger Federer 3.2% 47.6% 20 Carlos Alcaraz 3.2% 50.2%

When you can end points with your forehand twice as often as Federer did, you’re doing something right. The only players even close to the Brazilian’s winner rate end up losing far more points, probably because they need to take many more risks to get that small sliver of positive outcomes.

One more time for the road: Fonseca’s numbers are probably inflated due to his level of competition. In 2025, we’ll see how his forehand holds up against the elites. If we revisit these numbers twelve months from now, he’ll probably come down a notch. But raw power plays at every level. No matter who stands across the net, Fonseca’s forehand is fearsome–in all directions.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: