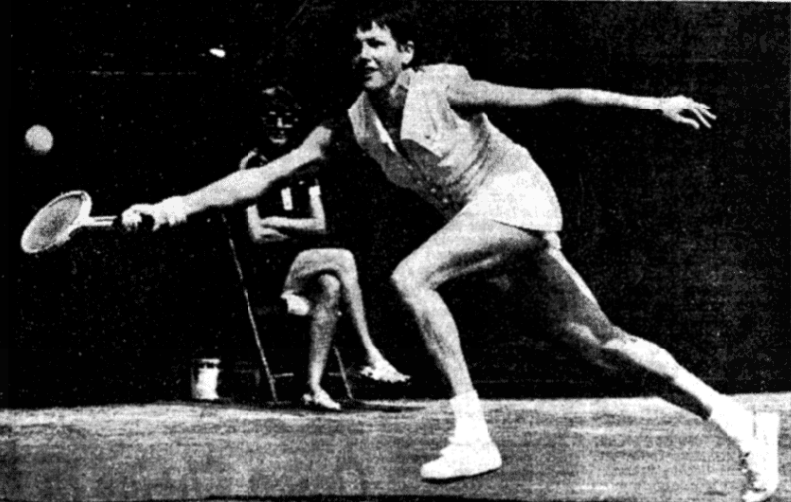

Chrissie Evert was only 18 years old, and she already had sportswriters reaching for their history books. Her matches with Margaret Court had become the most gripping rivalry in women’s tennis. In the final at the French, Court beat her in three bruising sets. At Wimbledon, Evert won a see-saw semi-final. Now they would meet again for a place in the US Open final. The New York Times compared the duel to “Wills–Jacobs” or “King–Richey”–in other words, the stuff of epics.

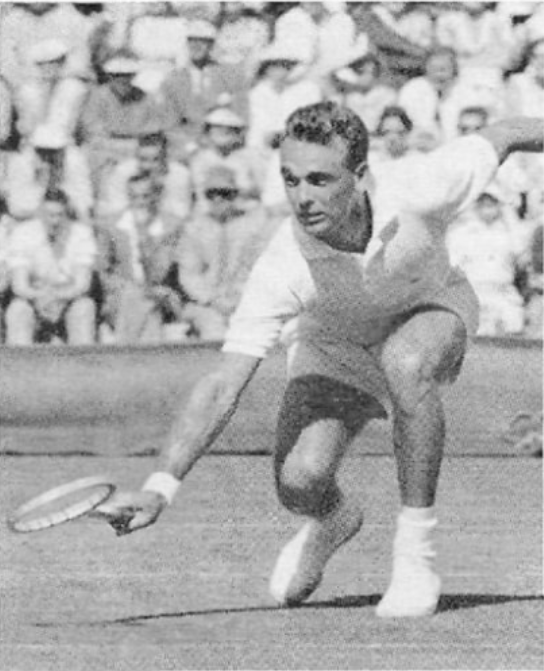

On September 7th, the ladies did not disappoint. The match showcased both players at their best. It also made a case for the equality–perhaps even the superiority–of women’s tennis. While many of the surviving men griped about the conditions, Court and Evert got down to business and grappled with the heat, the wind, and the divot-marred grass.

Margaret took an early 5-2 lead, then let it go when she abandoned her net attack to “sneak a rest.” A few lucky breaks went her way, and she escaped with the set, 7-5. The second turned into a baseline battle. After a series of long rallies and chalk-raising groundstrokes, Evert evened things up, 6-2.

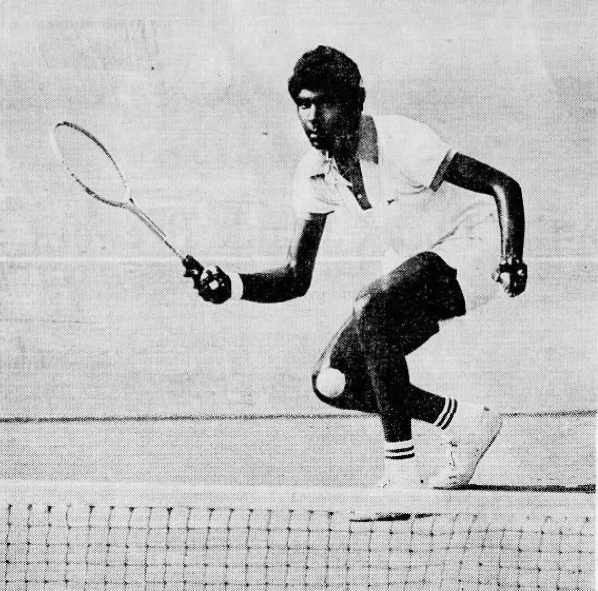

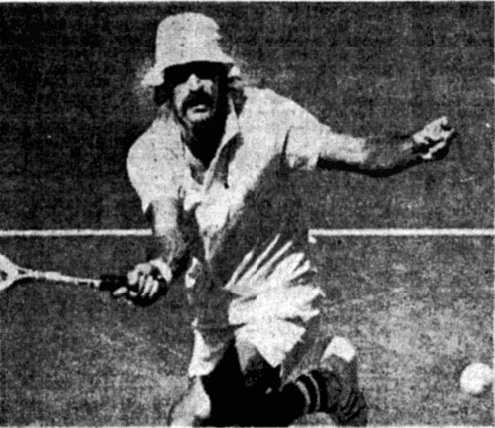

The Forest Hills crowd hadn’t seen much in the way of outstanding baseline play in 1973. A constant complaint throughout the event was the quality of the turf. Jan Kodeš, slated for a semi-final against Stan Smith the next day, had said, “You got to get to the ball before it bounces.” Other men registered their displeasure with New York’s air pollution. Combine all that with the heat and humidity, and no one was in the mood to slug it out from the backcourt.

Ultimately, Court’s big hitting won the day. She broke for a 3-1 lead early in the third. Chrissie earned two chances at 15-40 in her next return game, but the veteran erased them with a service ace and a line-kissing winner. Evert didn’t give up–three of the final four games went to deuce–but she never found a way back in. Margaret advanced to her 29th career major final, 7-5, 2-6, 6-2.

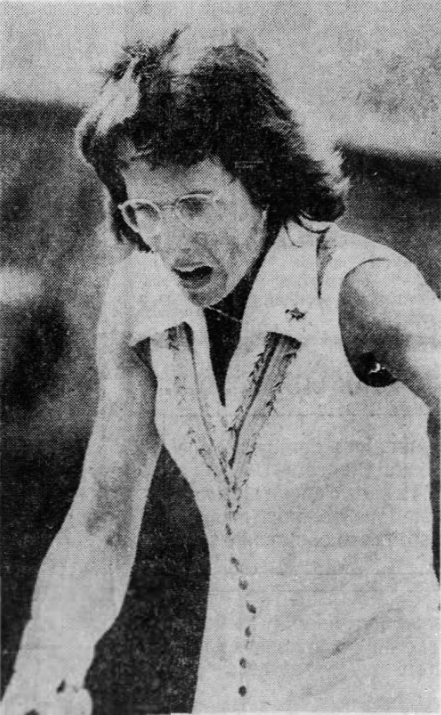

With Bobby Riggs set to take on Billie Jean King in just two weeks, it was tough to forget Court’s worst result of the year: her 6-2, 6-1 loss to Riggs in May. Four months on, it was tough to imagine such an overpowering yet versatile player losing to the duck-walking senior citizen. Margaret felt that way, too. “He fooled me that time,” she said. “I’d be ready for him now.”

For the Australian, though, the Battle of the Sexes was just a sideshow. Now, only Evonne Goolagong stood in the way of a fifth Forest Hills title, a 24th major overall, and a record-setting $150,000 in single-season prize money. She was more than just half of a great rivalry. Fans and pundits alike couldn’t help but think she might just be the greatest of all time.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: