There wasn’t much room at the top of the Virginia Slims circuit. Kerry Melville could have told you all about that.

One knock on women’s tennis was a supposed lack of depth. There were undeniable stars–Margaret Court, Billie Jean King, Evonne Goolagong–and a few more credible contenders, like Virginia Wade, Rosie Casals, and now Chris Evert. That coterie hogged the limelight; everyone else merely crossed their fingers when each week’s draw came out and hoped they’d find a path to the quarters. Lance Tingay ranked Melville fifth at the end of the 1972 campaign, but no one figured she was going to crack the inner circle.

The Australian earned her 1972 ranking by playing some of the best tennis of her career, picking up tournament victories on two continents with wins over Wade and Casals. She reached the final of the US Open, where she beat Evert before falling to King. Her runner-up status became a full-blown jinx in early 1973. She lost four finals in a seven-week span, every one of them to Court. Then she missed two weeks with a torn calf muscle.

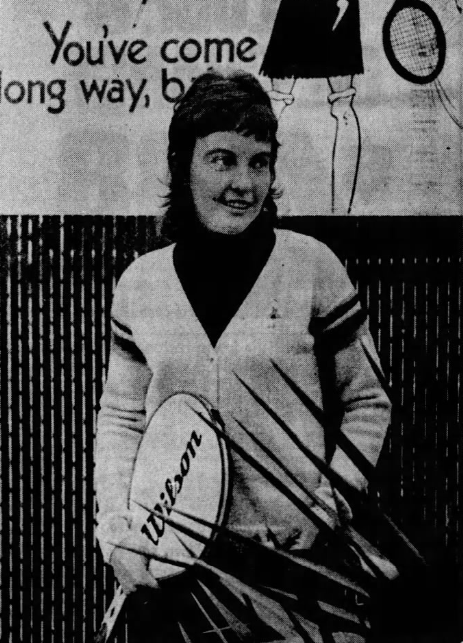

Things finally began to go Melville’s way in Tucson, the last week of March. The winter circuit was mostly played indoors, but despite unusually chilly, damp weather, the event in Arizona was held in the open air. Other players, including Casals, griped about the inconsistent conditions, but Melville (known as Kerry Reid after her 1975 marriage) preferred her tennis without a roof.

The second round brought the shock of the tournament. Court, who had lost just one match in nine 1973 tournaments, fell to an unheralded South African named Laura Rossouw. The wind and cold that affected Court’s concentration didn’t appear to trouble the second-seeded Melville: Kerry breezed through three rounds with the loss of only 13 games. Her semi was just as easy: Casals delivered “one service fault after another” and the Australian beat her, 6-1, 6-2.

The Tucson final, on April 1st, was no laughing matter. Nancy Gunter (formerly Nancy Richey) was one of the hardest hitters on tour. Both women aimed for the baseline and stripped any advantage from the server: No one held until the fifth game of the match. Gunter’s weaponry kept misfiring, and what could have been a lengthy war of attrition ended as a brisk, 6-3, 6-4 victory for the Australian.

Skeptics had reason to discount Melville’s title: King was out with a stomach injury, and Court lost early. But with a $6,000 winner’s check in her pocket, Kerry had an answer ready: “I suppose there will be people like that, but it still goes up on the board, doesn’t it?”

* * *

Elsewhere this week:

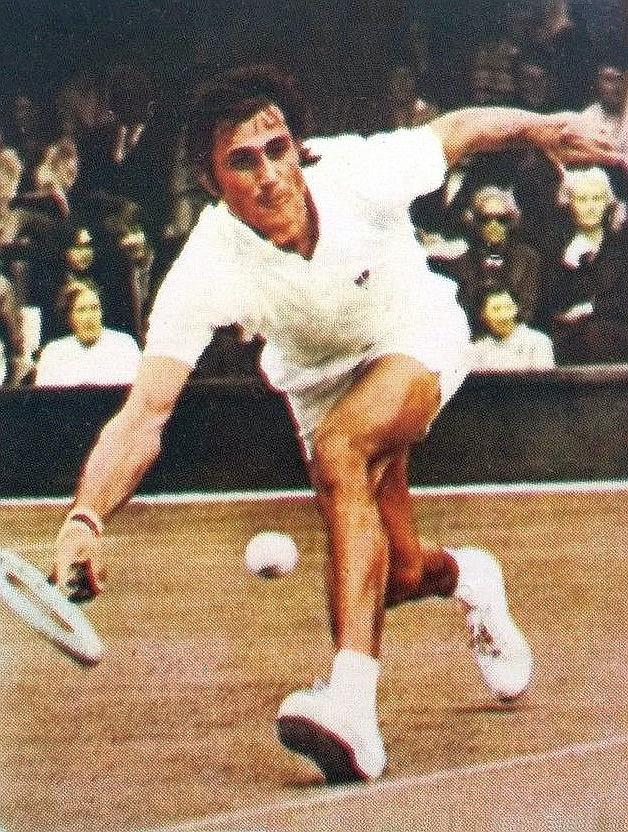

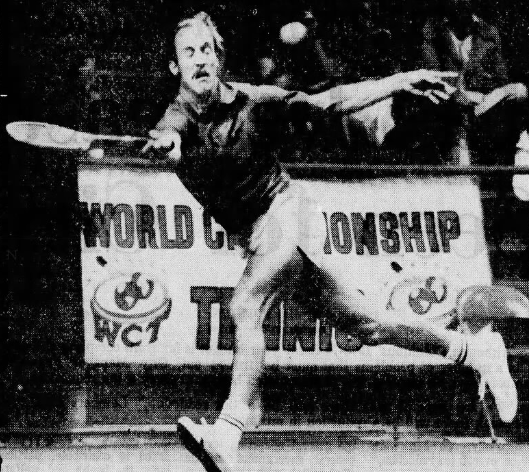

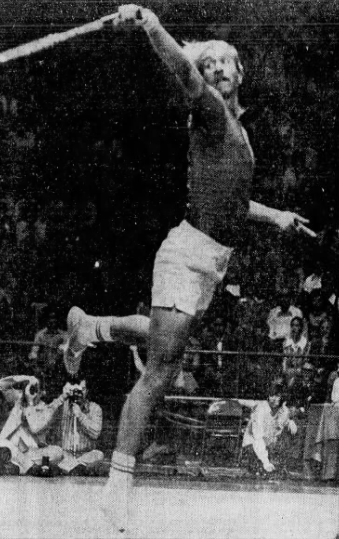

- In St. Louis, Stan Smith beat Rod Laver for the second straight week. This time it took three sets, but he finished the job with a break to love for a 6-4, 3-6, 6-4 victory.

- At the Lady Gotham Classic in New York, Chris Evert cruised to a 47-minute victory over Katja Ebbinghaus of West Germany. Looking on was Vice President Spiro Agnew, one of 2,401 spectators at Madison Square Garden’s Felt Forum. The $8,000 first prize increased Chrissie’s haul to $26,350 after just one month as a pro.

- Pakistan clinched its Davis Cup tie after squeaking through a five-set doubles rubber against South Vietnam. The victory earned them in a place in the Eastern Zone semi-finals against India, with the winner advancing to a likely clash with Australia.

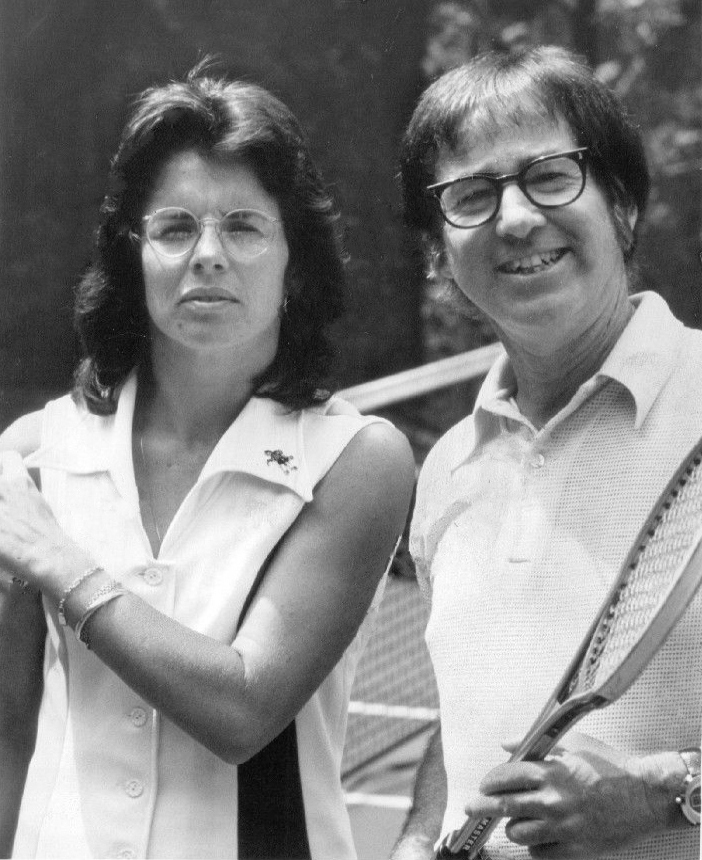

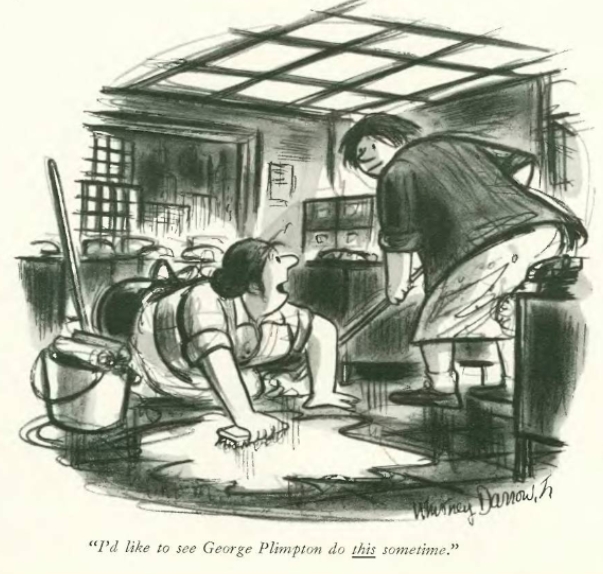

- Bobby Riggs told a reporter that women players shouldn’t get as much money as men, “because they’re not as good.” He also said that a no top woman had had a chance against a top man since Maureen Connolly in the 1950s.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: