When the United States opened its 1973 campaign in Mexico City on May 11th, it was already the tenth weekend of the year that featured, somewhere around the globe, a Davis Cup tie. Regional zones around the world progressed on different schedules, and the 53-nation draw made substantial demands of weaker countries. Canada and Colombia held an opening-round tilt in February, and when the Colombians took on Mexico a month later, it was already their third round.

The Americans, by comparison, had it easy. As defending champions, they received multiple byes. A few other countries did as well. The Romanians, among other European squads given first-round passes, wouldn’t get going for another week.

The byes carried a disadvantage, however. Once they took the court, there was no coasting past uncompetitive squads like Canada or Venezuela. The byes also cost Dennis Ralston’s US team the advantage of playing at home. They hadn’t played in the United States for two and half years, and they planned to host Mexico in Little Rock, Arkansas. Mexico protested to the ILTF, which sided with the underdogs. The Americans would head back to Mexico City, where they had swept the 1972 zonal finals just eleven months earlier.

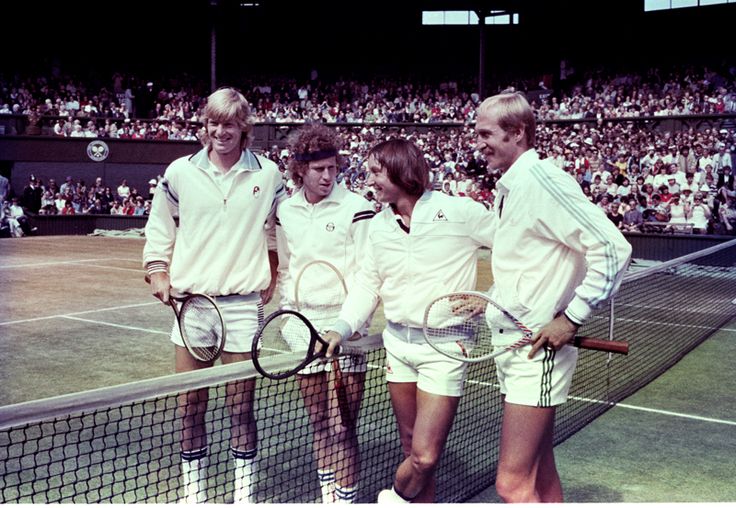

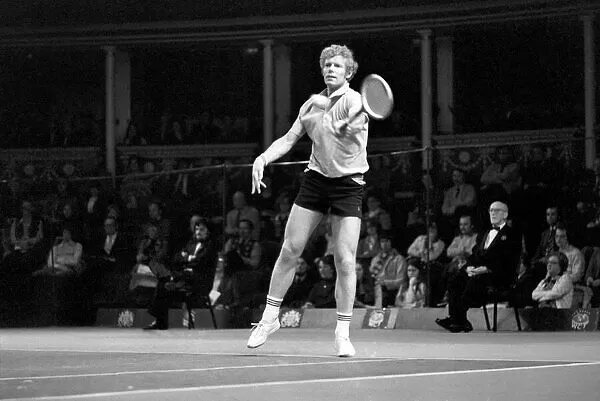

The team that flew south in May 1973 was not the same one that had made the previous trip. Stan Smith, linchpin of the US side, was top seed at the World Championship Tennis Finals in Dallas, contested over the same three-day weekend as the Davis Cup tie. Arthur Ashe and Marty Riessen, the next-best American players, were also in the eight-man WCT draw. 27-year-old Cup veteran Tom Gorman would lead the team instead. Ralston was lucky that Gorman hadn’t played a little better in March and April, or else he might have been in Dallas as well.

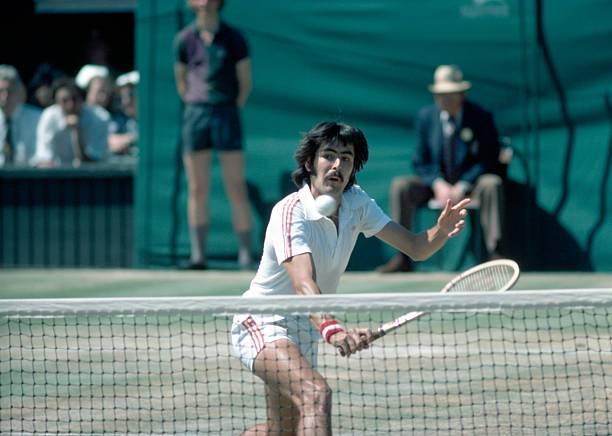

In 1972, Gorman had straight-setted Mexico’s Joaquín Loyo Mayo. This year, he found himself opening the tie against a fresh face, 19-year-old Raúl Ramírez. Ramírez had blasted his way through the American Zone, winning four singles and two doubles matches for his country in March. His Davis Cup momentum, combined with his proficiency on clay courts, carried over into the Gorman match. The newcomer made it look easy, defeating the American 6-4, 6-2, 6-3. It was over in less than two hours.

The upset drastically changed the outlook of the tie. Gorman was expected to win both of his singles rubbers. The other American singles options–20-year-old Harold Solomon and 22-year-old Dick Stockton–were less accomplished. Doubles stalwart Erik van Dillen mixed brilliance with a puzzling inconsistency. Suddenly, the Mexicans had a path to victory.

Coach Ralston didn’t relax for three more sets, until Solomon had polished off Loyo Mayo, 7-5, 6-4, 7-5. Solomon’s two-handed backhand and heavy spin were ideal for the surface, his attitude even more so. “He doesn’t have a big serve or volley,” said Ralston. “He’s just tough from the back and he never gives up.”

Knotted at one-all, the visitors were back in the driver’s seat. On May 12th, Gorman and van Dillen beat Ramírez and Vicente Zarazúa, dropping a 14-12 second set en route to a four-set victory. The next day, overshadowed by the exploits of Smith in Dallas and Bobby Riggs in California, Team USA would sweep the rest of the tie. They clinched when Solomon outlasted Ramírez, 8-6, 7-5, 7-5. They would face Chile in the American Zone finals in August.

Having cleared the initial hurdle, Ralston had plenty to look forward to. Smith would likely suit up for the next round, and best of all, they’d finally get a chance to play on home soil.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: