When Margaret Court was in form, playing a full schedule, the Grand Slam watch began on the first day of the season. She entered the 1973 campaign with a record 21 major titles, including the complete set in 1970. Number 22 came when she beat Evonne Goolagong for the Australian championship in January. She got past Goolagong again in the French semi-finals for a chance to play for her 23rd.

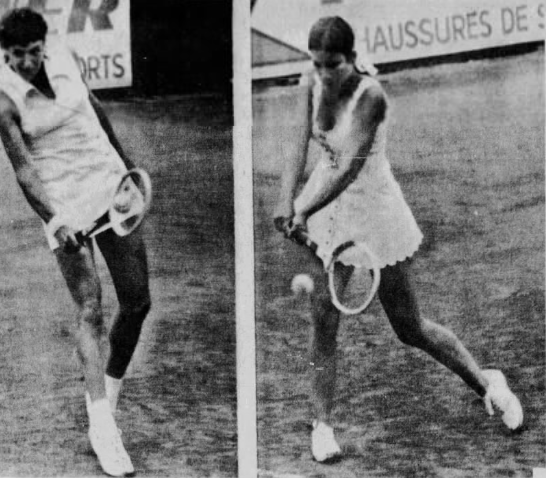

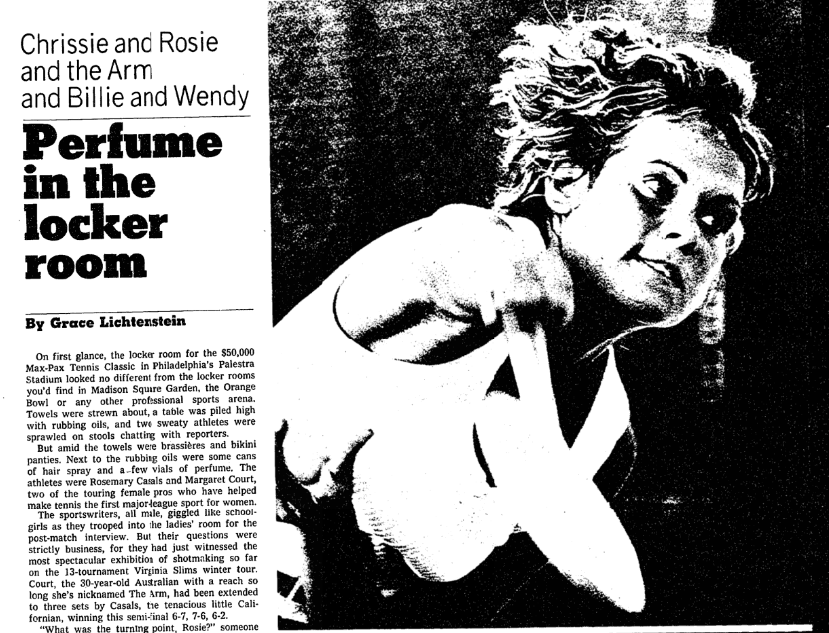

The final hurdle was the most hotly anticipated match of the women’s tennis season. Court and Chris Evert had dominated their respective tours. Evert was riding a 23-match win streak; Margaret had won 59 of 62 since the beginning of the year. Despite Court’s experience, there were reasons to favor the 18-year-old Chrissie in her first grand slam final. She had won three of four meetings, with a game better suited to clay. And Evert hadn’t just suffered an embarrassing defeat–with the world watching–to a 55-year-old man.

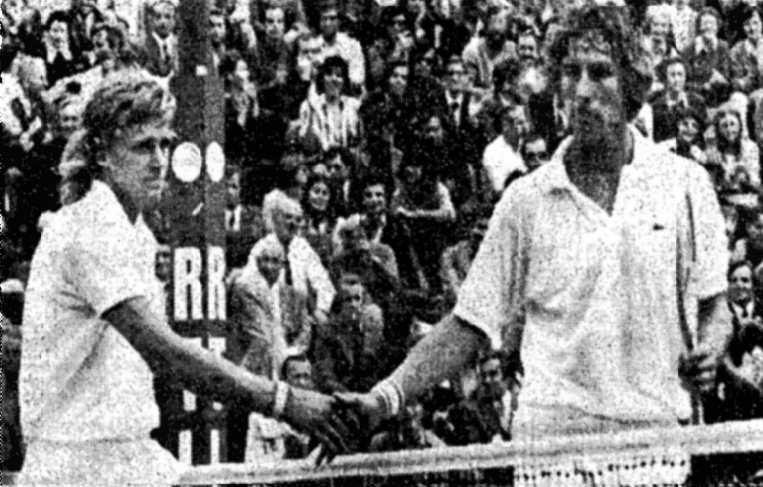

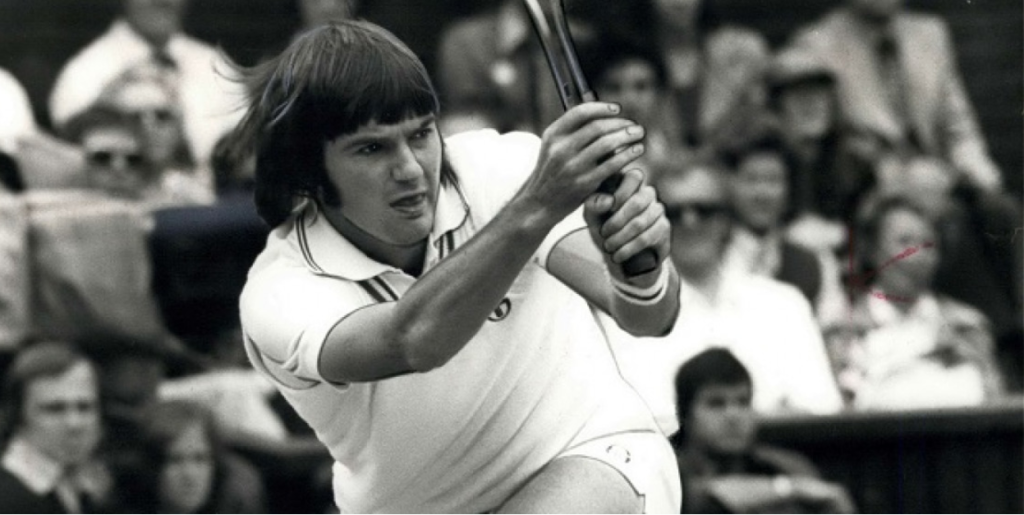

On June 3rd, the top two women in the game played a match for the ages. It was clear from the start that this wasn’t the same Court who had flubbed an exhibition just three weeks before. “I wish [she] had been in this form when she played Bobby Riggs,” said Chrissie afterward. “She would have hit him off the court.”

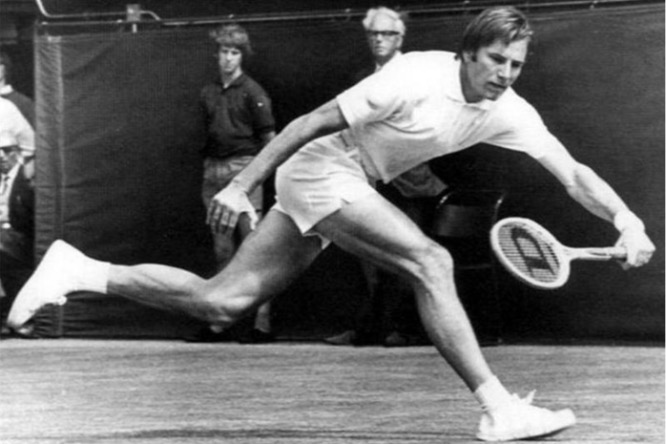

A week’s worth of rain had pushed the final back a day; it also delayed the start time. Tournament organizers, showing their usual gender preference, scheduled two men’s quarter-finals first. Evert was visibly jittery and lost four of the first five games. “It took me two or three games to find out where I was,” she said. “I had never seen so many people there before.” But the teenager warmed to the 12,000-strong crowd, dragged Court into longer rallies, and evened the score at 5-all. Margaret failed to convert two set points, then recovered to take a 5-2 lead in the tiebreak. Here Evert showed that she wasn’t overawed by the setting: She reeled off five points in a row to take the first set.

The second frame developed in the opposite fashion. Chrissie rode her baseline game to a 5-3 advantage, but failed to serve out the match. The set was decided by another tiebreak, this one perhaps the best tennis of the season. Both women aimed for lines and hit their targets. “In cold blood,” wrote David Gray for the Guardian, “no one would have taken such risks.” Court eked out the breaker, 8-6.

As the match passed the two-hour mark, Margaret finally took command. Neither woman had much left in the tank. Even Chrissie began to come forward in an effort to shorten points. That was all the opening that the veteran needed. The cramps that had taken her out of the Family Circle Cup threatened once again, but this time she could manage. “If my legs can hold out,” she told herself, “I can win.” They did, and she claimed the deciding set, 6-4.

“I must confess I didn’t know Margaret could play so well on clay,” Evert said. “It’s no disgrace to be beaten by Margaret.”

Chrissie was still slam-less, but more than ever, it was clear that she’d change that soon. Could Court hold her off for two more majors? She was now halfway to a second career Grand Slam.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: