Tennis people increasingly talk about “shot tolerance.” What does it mean?

There’s no standard definition. A Google summary settles on this: “a player’s ability to get to and return a given ball as desired.” Other definitions focus more on avoiding unforced errors: How long can a player stay in a rally without making a mistake?

I think of it like defense, in a very broad sense. Usually when we talk about defensive skills, it’s a lunging Andy Murray, recovering balls that nearly end the point, like big serves or would-be winners. In pro tennis, though, nearly every shot has an offensive component. That is to say, almost every shot tests the defensive skill–or resourcefulness, or shot tolerance–of the other player. A heavy Jannik Sinner forehand right at the feet, a Novak Djokovic backhand angled wide: Can you handle that and keep the point alive?

Another way to conceptualize shot tolerance is to imagine a win probability stat that updates with each shot. When Sinner hits that heavy forehand, his chances of winning the point against an average opponent increase to, say, 70%. A player with high shot tolerance will somehow save more than 30% of those points. A player with low shot tolerance will fail to get as many back (or hit weaker replies), and he’ll win fewer than 30% of those points.

We don’t have that all-knowing win probability stat, so we can’t measure shot tolerance so directly. Because the concept is fuzzy, I don’t imagine we’ll land on a fully satisfying way to quantify shot tolerance. But it’s worth the attempt, and it will help us explain how Rotterdam champ Carlos Alcaraz works his magic.

Long rallies

Start with the basics. Players with high shot tolerance should win more long rallies, right?

I drew the line at six shots, including rallies where the sixth stroke was an unforced error. I don’t want to muck things up by mixing surfaces, so we’re sticking with hard courts today. Based on Match Charting Project data, here are the men who have won the most of these “long” rallies on hard courts since the beginning of 2024:

Player 6+ W% Jannik Sinner 56.1% Carlos Alcaraz 55.6% Alex de Minaur 55.1% Grigor Dimitrov 55.1% Joao Fonseca 55.0% Learner Tien 54.5% Andrey Rublev 54.2% Novak Djokovic 53.7% Daniil Medvedev 53.7% Alejandro Tabilo 53.2%

The top of the list is as expected: Sinner and Alcaraz can outlast most opponents and have the ability to end the point. Fonseca and Tien probably won’t sustain these numbers, since they haven’t played the same level of competition as the others. Tabilo’s position is dicey, too, as we don’t have as many charted matches of his. Alexander Zverev is next on the list, if you’d like to promote him in Tabilo’s place.

Complicating matters is how these points end. The goal isn’t to sustain the longest rally possible. At some point shot tolerance gives way to power and calculated risk-taking. Some players are particularly strong on the pure shot-tolerance side of things, avoiding unforced errors in these long rallies:

Player 6+ Rally UFE% Casper Ruud 15.8% Bu Yunchaokete 17.9% Lorenzo Musetti 18.5% Daniil Medvedev 19.5% Alex Michelsen 19.5% Frances Tiafoe 20.0% Karen Khachanov 20.2% Alejandro Tabilo 20.4% Learner Tien 20.7% Novak Djokovic 21.0%

There’s some overlap between the two lists, but not much. Sinner’s error rate is better than average, at 22.3%, while Alcaraz’s is worse, at 24.1%. In the Rotterdam first round against Botic van de Zandschulp, Alcaraz committed unforced errors on 40% of points that reached the sixth shot. He still somehow won half of the long points.

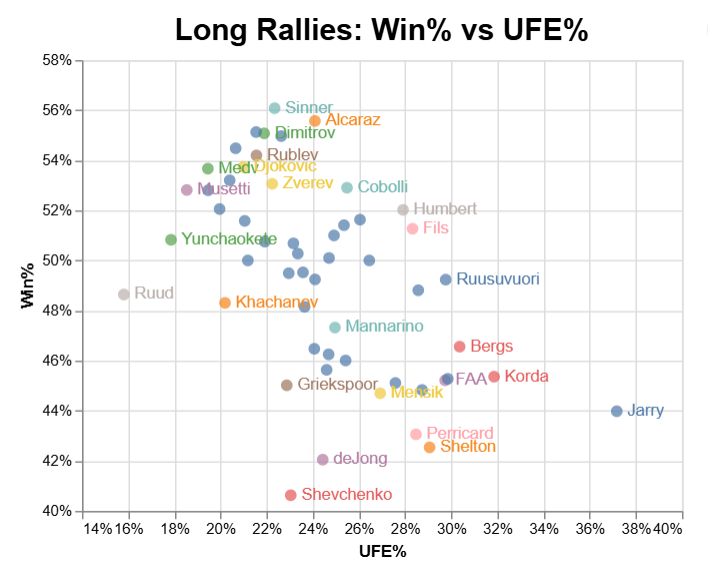

There’s a relationship between win rate and error rate on long points–there pretty much has to be, since errors are points lost. But error rate explains less than 30% of the variation in long-rally winning percentage. Alcaraz, for one, breaks the mold by committing a lot of errors yet winning the majority of the points:

Alcaraz’s errors don’t usually expose a weakness of shot tolerance. They reflect a gamble. (Sinner is similar, though his groundstrokes are so imposing that he can do more damage with less risk.) We can’t just count errors and create a shot-tolerance metric, but we also don’t have the ability to ask players what they were thinking when they attacked every shot. Isolating shot tolerance requires a different approach.

Accepting errors

Let’s shift from points to shots. Again for hard-court matches since the start of last season, I tallied each player’s baseline strokes starting from the fourth shot of each rally. Shot tolerance is useful for serve returns and plus-ones, but those shots are so often out of a player’s control. And since most points are short, returns and plus-ones end up dominating the data. To get a sample of shots that reflect what we think of as “rallying,” we need to discard those.

(The word “baseline” is doing a ton of work here. Shot tolerance isn’t usually about making volleys or smashes, or about executing passing shots. So I’ve excluded every shot at the net, as well as every shot when the opponent is at or approaching the net.)

As with the long rallies, we can start by getting a sense of the shot-tolerant all-stars, the guys who are best at avoiding unforced errors:

Player UFE/Shot % Learner Tien 7.4% Alexander Shevchenko 7.9% Lorenzo Musetti 8.2% Alejandro Tabilo 8.2% Tommy Paul 8.7% Frances Tiafoe 8.9% Carlos Alcaraz 9.2% Jannik Sinner 9.2% Matteo Arnaldi 9.2% Casper Ruud 9.7%

Musetti, Paul, and Ruud are names you’d probably expect to see here. Alcaraz and Sinner are more bracing. They don’t stand out as error-avoiders when we look at long rallies, but on a per-shot basis, they do.

In general, there’s a predictable trade-off. Players who hit more winners (and force more errors) commit more unforced errors. But the relationship between the two numbers is not the same for everyone. Here’s the same UFE-top-ten list, with winner rates added:

Player UFE% W+FE% Learner Tien 7.4% 7.3% Alexander Shevchenko 7.9% 9.1% Lorenzo Musetti 8.2% 9.1% Alejandro Tabilo 8.2% 10.6% Tommy Paul 8.7% 11.1% Frances Tiafoe 8.9% 8.0% Carlos Alcaraz 9.2% 10.1% Jannik Sinner 9.2% 14.1% Matteo Arnaldi 9.2% 8.3% Casper Ruud 9.7% 11.1%

Holy Sinner! The typical ATP regular hits slightly more winners than UFEs at these stages of the rally. Tien, Tiafoe, and Arnaldi are on the wrong side of the scale. Tabilo, again, is probably favored by a limited (and biased) sample. And Sinner … well, you need to go 15 more players down the list before you find anyone who cracks as many winners as he does, and Karen Khachanov coughs up a quarter more errors to accomplish the feat.

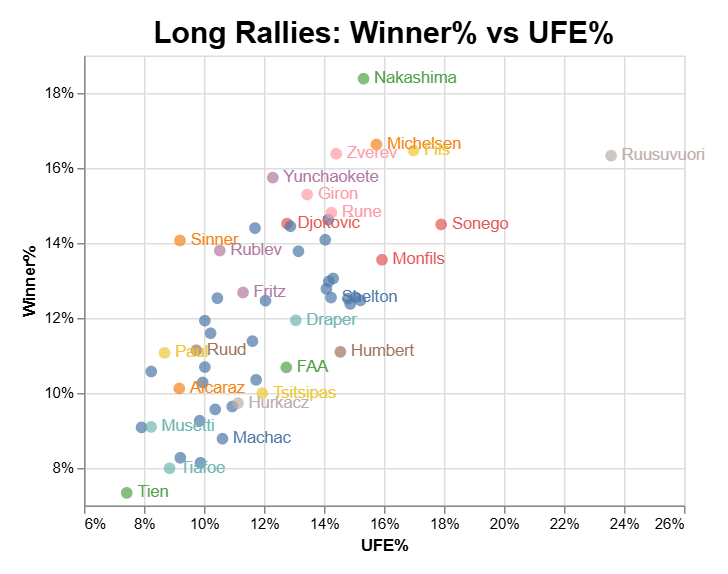

Here’s the full scatterplot:

This is a tighter relationship than the one pictured earlier. The player-to-player variation in winner rate explains half of the difference in error rate. Yet again, some players defy the usual tradeoff. The closer they are to the upper left corner of the graph, the more risk-free their aggression.

Controlled (for) aggression

It feels weird to quantify shot tolerance by considering winners, but that’s exactly what we’re going to do.

As a simplification, imagine that we put every shot into one of two categories: aggressive or defensive. Aggressive shots really aren’t about shot tolerance. Unless the aggression is just a last-ditch effort from a hopeless position, it’s a shot that the player more or less knows he can make. He hits hard, aims for the line, and it ends the point one way or the other.

Shot tolerance isn’t about the unforced errors that come from that kind of risk. We’re interested in how steady a player is on every other shot.

To get there, we’re going to string together some assumptions. You’ll probably disagree with some of them, and you’ll almost definitely disagree with some of the results. But bear with me for a minute anyway.

Say that the “cost” of winners (and forced errors) is half as many unforced errors. The usual ratio is closer to 1:1, but that doesn’t count forced errors, and it counts the kind of “bad” errors that come from low shot tolerance. So the 2:1 ratio means that if a player is going to hit two winners, the cost of doing business is one unforced error. For Alcaraz, his 10.1% winner rate implies that even if he’s playing flawlessly in non-aggressive situations, he’ll still have an error rate of about 5%.

From there, we come up with a “non-aggressive” error rate. Since Alcaraz’s total error rate is 9.2% and we’re writing off 5% as the cost of his aggression, that leaves us with 4.2%. We’ll divide that by the number of non-aggressive shots–that is, 100% of his shots, minus his winners, minus the 5% of aggressive errors. So: 4.2% divided by (100% – 10.1% – 5% =) 84.9%. Punch it into the calculator, and we get a non-aggressive error rate of 4.9%.

In more positive terms, that’s a “shot tolerance” of 95.1%. That is, when he has a reasonable chance of making a shot (meaning his opponent didn’t hit a winner or generate a forced error), and he doesn’t go big, he makes the shot 95.1% of the time. Average among tour regulars is 93.7%. Here are the top ten, excluding the names like Tien and Tabilo that I quibbled with above:

Player ShotTol Jannik Sinner 97.3% Tommy Paul 96.2% Lorenzo Musetti 95.7% Andrey Rublev 95.4% Carlos Alcaraz 95.1% Grigor Dimitrov 95.0% Casper Ruud 95.0% Daniil Medvedev 94.9% Frances Tiafoe 94.5% Alex de Minaur 94.4%

So, do you agree that Alex de Minaur doesn’t have the shot tolerance of Rublev, Dimitrov, or Tiafoe? What about leaving Djokovic out of the top ten entirely? (His figure over the last 13 months is a below-average 93%.) Of course you don’t. That’s what I’m here for.

Djokovic is easy enough to explain. His last 13 months have been rocky. If we expand the time frame back to 2020, his number shoots up to 97.1%.

Dimitrov is higher than expected because of his reliance on the slice. Dan Evans did well by this metric, too. Slices are a good way to keep balls in play, even if they don’t generate a lot of offensive opportunities. I hesitate to exclude slices from the metric, but some kind of adjustment is probably in order.

De Minaur may expose another limit of this approach. One of the assumptions I strung together is that everyone’s winners come at the same cost. But the Aussie is relatively small: He can’t just wave a magic wand and generate winners like Sinner can. He needs to take more risks to end points. His winner/error ratio for this set of shots is 10.7% to 10.0%. My model assumes that a bit more than half of his errors are aggressive shots that missed the mark. But what if it’s more? In the bizarro world where players really did register their intention before every shot, we might find that many more of de Minaur’s errors fall in that category.

Or, maybe, he’s not quite as sturdy as we think he is. Either way, it’s something to watch next time you tune into a match of his.

Return to Alcaraz

Why, then, is Carlitos’s name in the headline? Sinner (or Tien, or Ruud) is better by most of these metrics.

What fascinates me about shot tolerance is what it doesn’t explain. If shot tolerance determines anything, it should tell us who’s going to win long rallies. And to some extent it does: Sinner tops the shot tolerance list, and he wins more long rallies than anybody else. (Though that doesn’t prove much: Sinner is better at just about everything, related or not.)

Yet Alcaraz isn’t far behind in long rallies. The Spaniard comes in second with room to spare. Tommy Paul does better on my shot tolerance metric, yet he wins only 51% of long rallies.

The X-factor, I think, is that shot tolerance is instrumental. You can win some points by out-shot-tolerancing your opponent, because yes, eventually they will miss. But nearly as often, you will keep the rally alive, even slightly in your favor, and they’ll take a risk that pays off. If that opponent is Sinner, that’s the most likely outcome. Just ask de Minaur, who has lost all ten of his career meetings with the Italian.

Alcaraz’s long-rally magic doesn’t fully show up in the shot tolerance metric because it isn’t confined to the baseline. The signature Carlitos point is a ten-stroke rally that he puts away at the net or polishes off with a drop shot. His baseline prowess isn’t quite a match for Sinner, and his net skills probably rank behind those of Federer or Nadal. But has there ever been a player who could go from gutbusting rally to all-court acrobatics with such success?

The Spaniard approaches the net half-again as often as Sinner does. He wins nearly three-quarters of points when he does so. In today’s game, a mid-rally net approach has to be earned, and many strong forecourt players don’t have the baseline skills to create those chances.

Shot tolerance, then, is necessary but not sufficient. (And that’s even ignoring short points. Impregnable rallying doesn’t count for much when the serve is unreturnable.) Sinner earns his point-ending chances with sturdy baseline work, then converts them from the same position. Alcaraz is nearly as good at keeping the point alive, and he has more options than anybody when it comes to finishing it.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: