We’re lucky that it was a bit of a slow news day for tennis on March 24, 1973. A few newspapers had room for this:

PHILADELPHIA–The local team of James L. Van Alen 2d and Jimmy Dunn won the United States amateur-professional handicap court tennis doubles championship today by defeating George Plimpton and Eddie Noll of New York, 6-5, 6-5, 3-6, 6-4, at the Racquet Club.

Yes, that Jimmy Van Alen. And yes–oh yes!–that George Plimpton.

Van Alen was, depending on your perspective, somewhere between a gadfly and a visionary. He invented the tiebreak and spent more than a decade badgering the rest of the US tennis establishment. Even when his brainchild became standard, he wasn’t satisfied. His ideal was a nine-point breaker: first to five, sudden death. As the first-to-seven, win-by-two variation gained popularity, he got steadily crankier about it.

Details aside, the man loved tiebreaks. He proposed that once a set reached 6-all, a special red flag would be flown above the stadium to indicate that a tiebreak was underway. He convinced the officials at the US Open to go for it, and when he attended other events, he brought along a spare flag of his own.

In 1973, Van Alen was 70 years old. He was far past his prime as a lawn tennis player, and he had never been a particularly great one. (He did win a match at the 1931 US National Championships.) His pastime of choice was court tennis, the ancient sport on which lawn tennis was based. Court tennis is a more strategic game that relies less on power. Van Alen won national singles and doubles titles in his niche pursuit.

Van Alen’s prestige gave him another advantage. This was an “amateur-professional” doubles championship–that is, one of each. Van Alen the amateur chose to team up with Jimmy Dunn, the head pro at the Philadelphia host club. It always helps to choose the right partner: It was Dunn’s tenth title at this event.

* * *

Van Alen was not, however, the most interesting man on the court that day. Few characters could compete with George Plimpton in that category.

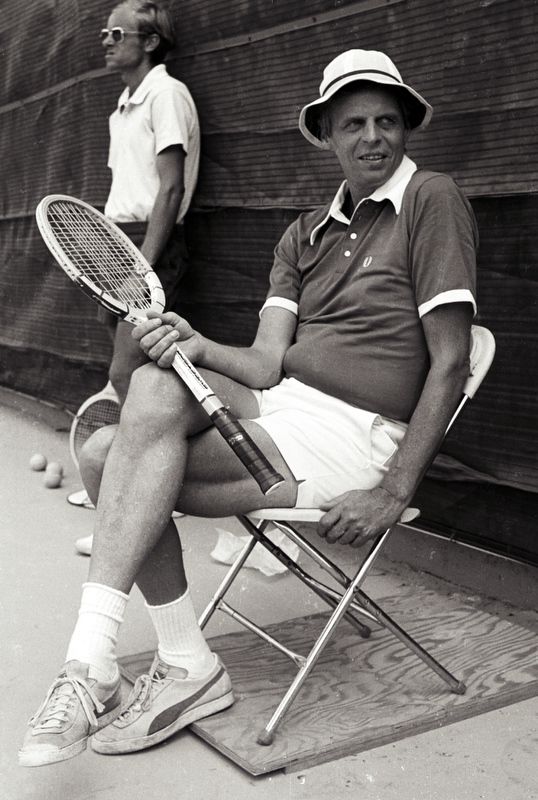

Plimpton was a journalist and occasional actor. By 1973, he was 46 years old and a minor celebrity. Despite a patrician background that could be traced back to the Mayflower, Plimpton got closer to the action than any sportswriter before him. He pitched to major-league all-stars, traded punches with Sugar Ray Robinson, and manned the net for hockey’s Boston Bruins.

He achieved his fame through dalliances in football and golf, yet when he wasn’t on assignment, tennis was his sport of choice. The writer was known as an excellent lawn tennis player, and he occasionally turned up in pro-am exhibitions. When he got married in 1968, the New York Times went with the standard line for a racket-wielder: “Plimpton Drops Singles for Doubles.” A decade later, he played alongside Vitas Gerulaitis as a headliner at a Rockefeller Center benefit match–on ice.

Among his many stunts, he once faced off against Richard González at the Los Angeles Tennis Club. Gorgo wasn’t one to show mercy on an amateur, and the fact Plimpton was a journalist probably didn’t help either. González destroyed him.

Like Van Alen, Plimpton found a home in the small world of court tennis. He had competed at national events since at least 1961. He merged his profession and his passion in 1971 when he edited Pierre’s Book, the instructional guide written by French court tennis great Pierre Etchebaster.

Despite an advantage of more than two decades, Plimpton doesn’t seem to have been Van Alen’s equal at the royal game. In that 1973 championship match, his pro partner, Eddie Noll, had to handle three-quarters of his team’s shots.

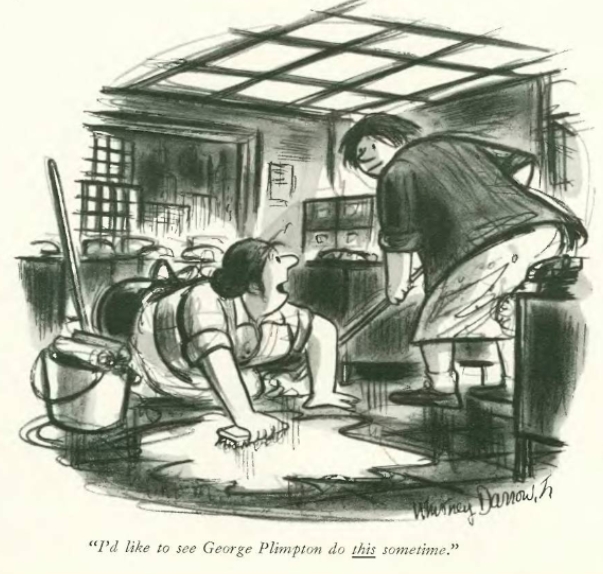

Unfortunately for us, Plimpton never wrote much about the sport he pursued so avidly. He covered lawn tennis just once for Sports Illustrated, the publication that backed him on some of his wilder adventures. For that 1967 story, he was drawn to a series of unusual matches at Southampton and Newport–early-round tilts that refused to end, extending to 32-30, 48-46, and 49-47. Naturally, he checked in with the tournament director at the Newport Casino, Jimmy Van Alen.

“That’s nonsense out there,” said the inventor of the tiebreak. “Just nonsense.”

* * *

This is the second installment in what I fear will be an ongoing series about 1973, perhaps the most consequential season in modern tennis history. Check back throughout the year for the latest news from, uh, fifty years ago.