Wimbledon was nothing if not predictable: Immaculate lawns, surging crowds, and the struggles of Virginia Wade.

“She goes on to court burdened with the weight of every national hope,” wrote David Gray in the Guardian. “She has played eleven times at Wimbledon and she has reached the quarter-finals only twice…. [U]p to now she has either disappointed and slumped against less talented and less fancied opponents or else she has lost to her old enemy, Billie Jean King.”

If the tournament ever needed Ginny to pull through, this was the year. The 1973 Championships were marred by a boycott of more than half the men’s field. This would be a “Women’s Wimbledon” in which the ladies would carry more of the burden than usual.

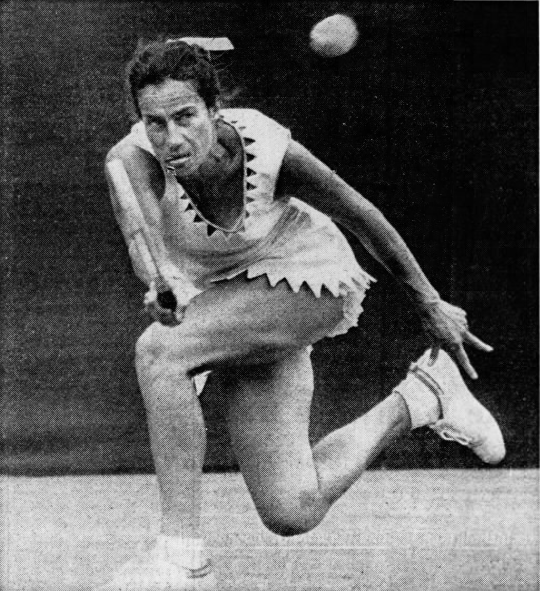

In her first outing of the fortnight, on June 26th, Wade didn’t exactly silence the doubters. She took on 16-year-old Australian Dianne Fromholtz, a lefty who had emerged as one of the game’s top prospects. The youngster had already won four minor titles in England and put together a 12-match winning streak on grass. She arrived on Centre Court and acted like she belonged there.

Fromholtz opened play with an ace and remained on top with a barrage of forehand winners. The pressure was all on Wade, who responded with enough unforced errors to allow her opponent to cruise to a one-set advantage, 6-3.

“I wish they would not sigh every time I miss an easy shot,” Virginia said of the home crowd.

Experience, eventually, told. Fromholtz felt the weight of her half-accomplishment, and Wade zeroed in on her backhand. The veteran took control of the net, discovering that her opponent had no lob to speak of. Wade rebounded with a 6-2 second set and was even better in the third. She won the last 14 points of the match to seal it, 6-1.

Still, it was hardly an inspiring start for the sixth seed, especially on a day when her “old enemy,” Billie Jean, advanced with the loss of just two games.

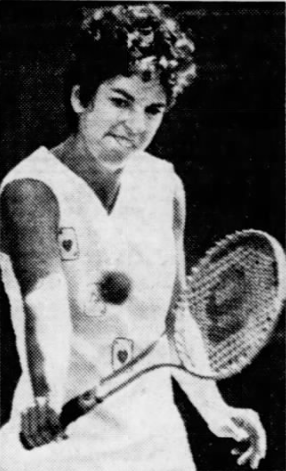

At least Wade fared better than another British heroine, 1961 finalist Christine (Truman) Janes. Janes also drew a left-handed 16-year-old, Martina Navratilova. Janes had learned her name only two days earlier, yet the Czech won in straight sets. “Now that I have played her,” said the Brit, “I am not surprised that she beat me. I think that she is good enough to push most of the players here.”

* * *

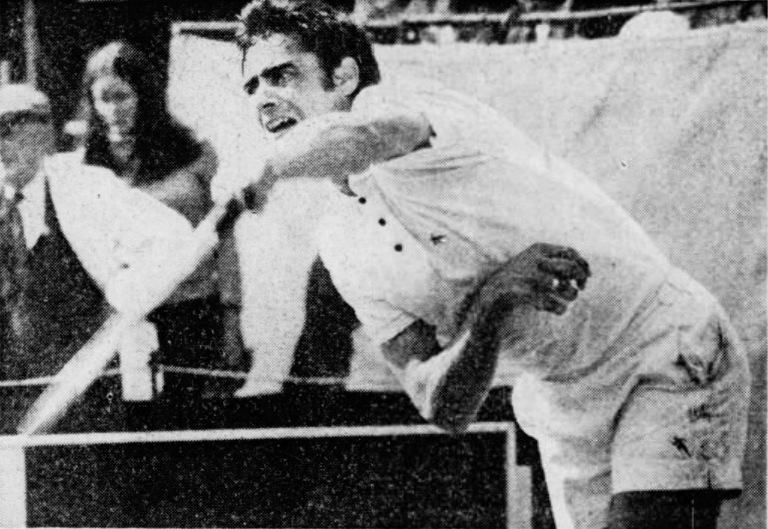

Back in New York, Bobby Riggs was playing exhibition matches with his pal, 62-year-old baseball legend Hank Greenberg. At a resort in the Catskills, the geriatric pair defeated a couple of younger opponents. Bobby did the math and made sure the crowd knew the exact age gap.

Riggs continued to aim for bigger prizes. “After I beat Margaret Court, she said there were seven women, including herself, who could beat me,” Bobby said. “I want all seven of them.”

“Right now I’m on my way to scout the women at Wimbledon. My goal is a match with the Wimbledon champion for $100,000, winner take all.”

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: