Every time tennis’s rival groups reached an agreement, another interloper entered the field. Top players were free agents, and there was so much money up for grabs through television broadcasts and commercial sponsorships that the cycle seemed like it might continue forever.

The ILTF-backed Grand Prix had come to terms with World Championship Tennis in late 1972, granting the US-based WCT circuit four uncontested months at the start of each calendar year. That left the Grand Prix more than half the year to fill with the traditional federation-sponsored events, including the four majors.

The peace lasted less than a year. World Team Tennis was the latest newcomer, and it laid a claim to a prime segment of the season between May and July. Wimbledon wasn’t directly under attack–WTT franchisees said they would break for the Championships–but the French, the Italian, and a slew of other traditional events had new reasons to worry about attracting talent. The WTTers were parvenus, but they had enough money to cause problems. In its inaugural player draft, the league divvied up the rights to every single player of note.

On August 8th, Commercial Union–the title sponsor of the Grand Prix–made its move. A spokesman for the insurance group announced the plan for 1974: an expanded slate of 15 tournaments with prize pots of at least $100,000, including the majors. Players would be eligible for a bonus pool–and here’s the kicker–only if they entered a certain number of designated events.

Put another way, stars who passed on World Team Tennis would have a new end-of-season payday to aim for.

The explicit goal was to get more big-name players at more Grand Prix events:

In the past some tournament organisers have not known sufficiently well in advance which players would compete and this is most important since they wish to obtain the best terms of sponsorship and television.

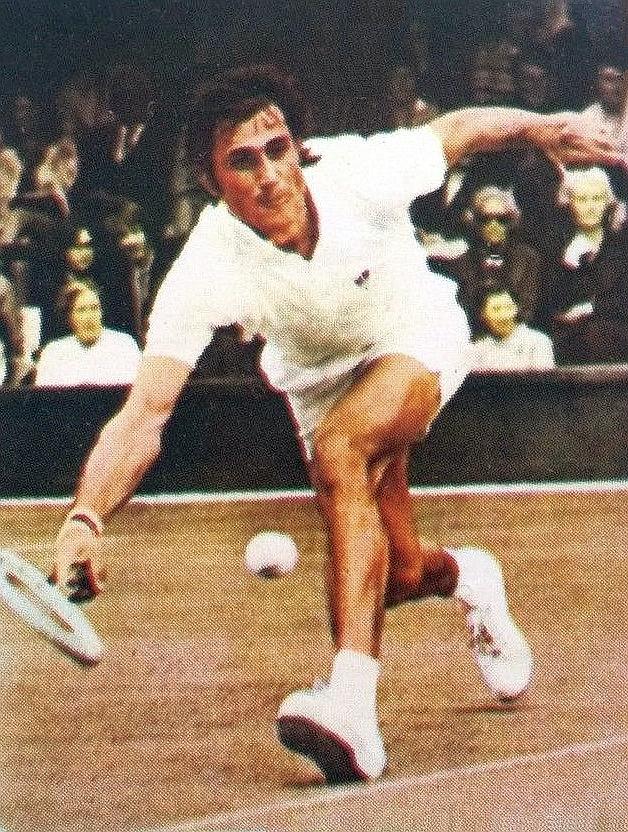

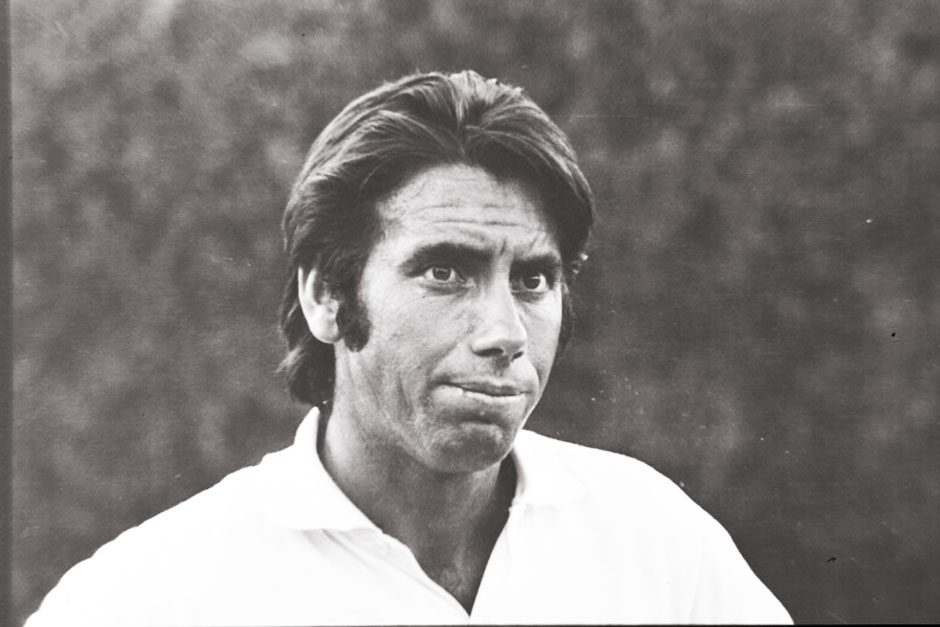

Pro tennis was tied in a knot that it still hasn’t entirely figured out how to undo. The marquee names were immensely valuable, worth more than most events could offer in prize money. Their popularity, though, depended on conquering the familiar circuit. Take Davis Cup and Wimbledon away from Stan Smith and you were left with a B-lister. The tournaments succeeded on the backs of players–preferably, all of them. But men who had already earned their reputations–Smith, Rod Laver, Ilie Năstase, John Newcombe, Ken Rosewall, and others–could cash in their celebrity without entering 30 tournaments a year.

Both sides needed the other, but the tournaments needed the players more.

Team Tennis threatened to disrupt what fragile balance remained. One-off, made-for-television exhibitions were the scourge of traditional tournament promoters. WTT’s proposed 44-match schedule was that much worse.

Federation officials dreamed of getting the stars back under control. Only six years earlier, tournaments didn’t even offer prize money, and top players (usually) went where the bureaucrats told them to go. Now, the athletes were getting rich, and like their colleagues across all major sports, they sought even greater control of their destiny. Free agency was inching toward reality in Major League Baseball. The same day as Commercial Union’s announcement, a judge in the United States ruled in favor of the World Hockey Association, which sought to sign players whose National Hockey League contracts expired. A proposed merger of the National Basketball Association and the American Basketball Association was held up in the courts by hoopsters concerned about their bargaining position.

The future belonged to the players. First, though, there were more skirmishes to fight. Team Tennis, it was becoming increasingly clear, would provide the next battleground.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: