There was no better encapsulation of the 1973 tennis season than the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Pro-Celebrity Tournament, held at Forest Hills on August 25th, a few days before the US Open was set to begin. The field was packed with tennis stars, Hollywood idols, and Kennedys.

And Bobby Riggs stole the show.

Ilie Năstase played doubles alongside Walter Cronkite. Davis Cup captain Dennis Ralston teamed up with NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle. Ethel Kennedy showed off groundstrokes that would have passed muster on tour. Sidney Poitier held a hand-shaking session–“no autographs, just handshakes.”

So many celebrities took part that the most famous tennis players in the world blended into the background. Stan Smith was forgotten next to his doubles partner, Merv Griffin. Björn Borg, who had attracted so much attention at Wimbledon that the groundskeepers feared his teenage fans would destroy the turf, was ignored entirely.

Some of the stars even cared about tennis. Dustin Hoffman won the event in 1972. “This means more to me than my family,” he said as he attempted to defend the title.

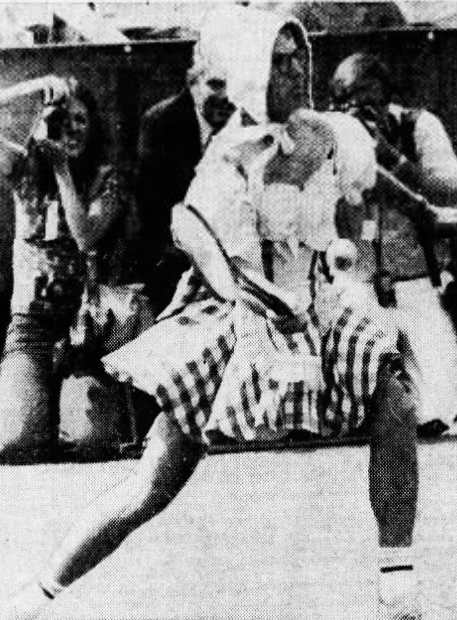

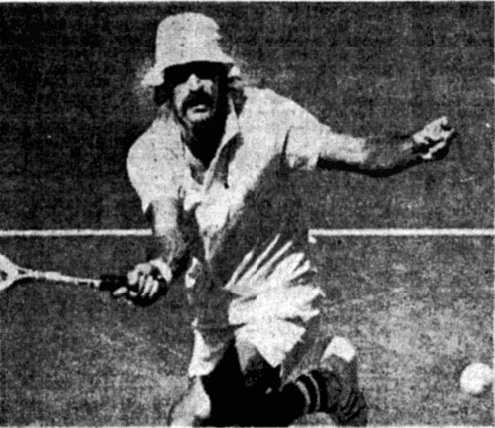

But no one could compete with Bobby Riggs. The 55-year-old Happy Hustler was a walking advertisement for his match against Billie Jean King, now 26 days away. Riggs showed up in a red minidress–“Little Red Riding Hood in drag,” according to the Daily News.

Despite the getup, Riggs singlehandedly took on comedians Alan King and Bill Cosby. Bobby won the first point with a trick serve that barely cleared the net. Cosby was realistic about his chances: He kept a cigar in his mouth for the entirety of the three-game “match.” Riggs won it, 3-0.

He agreed to a rematch–another opportunity to show off. The teams bet $100 a man, with numerous handicaps in place to slow down the former Wimbledon champion. Riggs had to carry valise containing a heavy rock and sit in six chairs placed around the court. All while wearing a trenchcoat–but that might have been a courtesy for those fans who had seen the minidress fall down one too many times.

This time, King and Cosby won. “If they were woman comedians,” said Riggs, “I would have bombed them right out of their socks.”

It was never about the tennis, of course. The stated purpose of the event was to raise money for disadvantaged children. Really, it was an opportunity for the “beautiful people” to mingle. Tennis had always been a rich man’s game. Now tradition was turned on its head: 15,000 fans could come out and watch famous faces try to keep the ball in play. At the height of the tennis boom, it didn’t even really matter if the celebrities could play. A movie star holding a racket was enough.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: