Top dog John Newcombe must have yearned for the days when Australia produced a seemingly endless parade of up-and-comers. Tennis’s center of gravity had decidedly shifted to the United States–Newk was one of many foreigners with a home in the States–and when a new face appeared in the late rounds of a tour event, odds are he was American.

The first of week of October 1973, it was Eddie Dibbs’s turn. “Fast Eddie” was a two-time All-American at the University of Miami. In his first year as a full-time pro, the 22-year-old offered a few hints of stardom, picking up two titles against second-tier and knocking out Stan Smith in Toronto. At the US Open, however, he won just six games against countryman Tom Gorman.

Dibbs won his first two matches at the Colonial Pro in Fort Worth, earning him a place in the quarter-finals against top seed Newcombe. Newk had continued streaking after winning the Open a few weeks before. The adopted Texan had picked up a title in South Carolina, then fell to Tom Okker in the Chicago final a week later. Eyeing the number one ranking, the mustachioed master was no longer a part-timer: He would play every week up to Australia’s next Davis Cup date in mid-November.

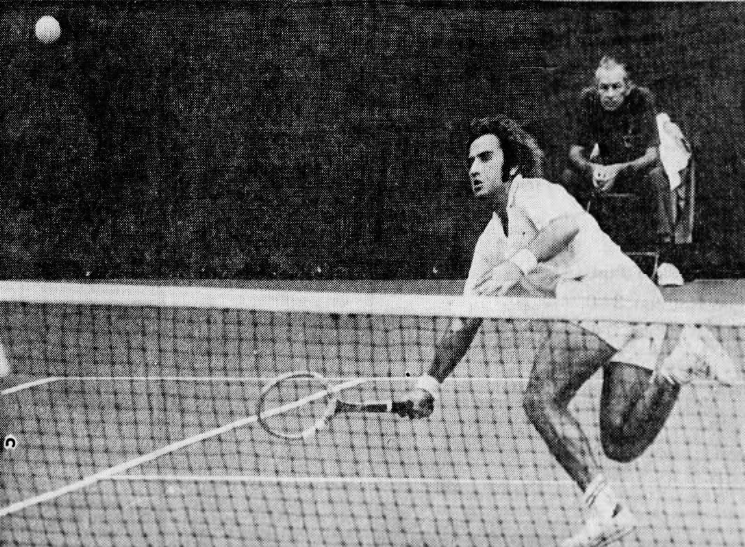

Rain wiped out the quarter-final slate on Friday, so the two men met on Saturday, October 6th. The contrast could hardly have been greater. Newk converted every inch of his six feet into raw power. Dibbs… well, he was fast. Writing in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Mike Shropshire described Fast Eddie as “built along the lines of Mickey Rooney”–the five-foot, two-inch actor not known for feats of athletic prowess.

Dibbs’s five-foot, seven-inch frame hardly intimidated the Aussie, but it was enough to get a racket on Newk’s fabled serves. Overcoming a second-set lapse, the American scored the upset, 7-5, 1-6, 6-3.

“I returned unbelievably,” said Fast Eddie. “He’s got a huge serve, and I returned it.” Dibbs added another point to his own credit: The cement surface should have favored Newk and his cannonballs. Not today.

The 22-year-old carried his momentum into the semi-finals against another big hitter, Roscoe Tanner. Thanks to the previous day’s rain, there was little break. Dibbs relaxed as much as he could, watching the first day of the baseball playoffs on television. This time there was no mid-match lull: Dibbs outplayed Tanner in a first-set tiebreak, then sealed the victory with a 6-3 second set.

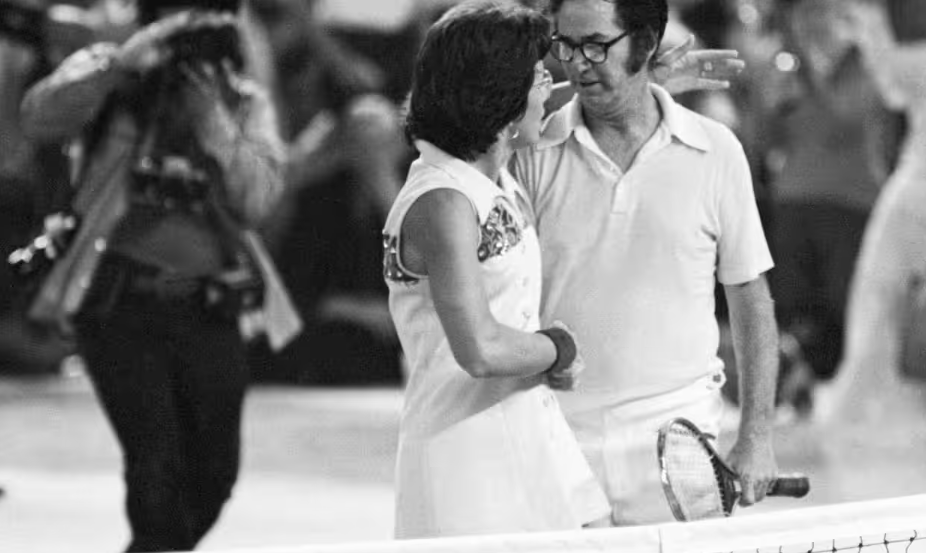

American players had been shut out of the championship matches at their home major, but Dibbs and another youngster, Brian Gottfried, would make it a red-white-and-blue final in Fort Worth. Newcombe’s assault on the number one ranking would have to wait.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: