Chris Evert played a lot of tennis in her home state of Florida, but at the end of 1973, she had to travel all the way to South Africa to establish her supremacy over Evonne Goolagong and the rest of the Grand Prix field.

For two months, Evert had held a modest lead in the Grand Prix points standings, a table based on the results of the season’s sanctioned tournaments. A lot hung on the word “sanctioned.” The Grand Prix was organized in part to help traditional events attract stars and fend off competition from World Championship Tennis and the Virginia Slims tour, so results from those upstart circuits didn’t count. Goolagong had made a late push by reaching the US Open final, together with titles at the Canadian Open and in Charlotte, where Evert had withdrawn due to illness.

The only Grand Prix event on the ladies’ calendar in the last quarter of 1973 was the South African Open. Goolagong was the defending champion; if she won the title again and Chrissie stayed home, the Australian would claim the Grand Prix crown and its $23,750 bonus. (The runner-up would collect a healthy consolation prize of $16,250.)

Airfare from Florida to Johannesburg wasn’t cheap, but with $7,500 on the line–not to mention another $6,000 for the South African title–it would be foolish to stay home.

On November 22nd, Evert justified the journey. By defeating 17-year-old local Ilana Kloss in the quarter-finals, she secured enough points to put the Grand Prix laurels out of reach, even if Goolagong defended her crown.

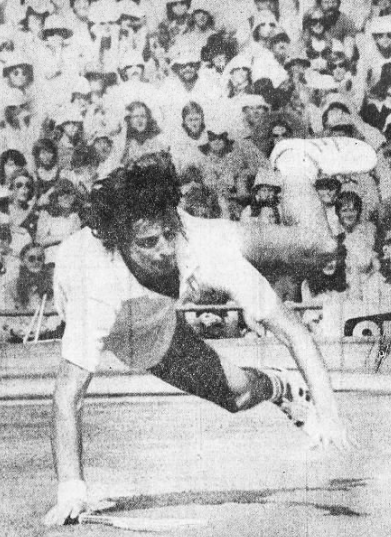

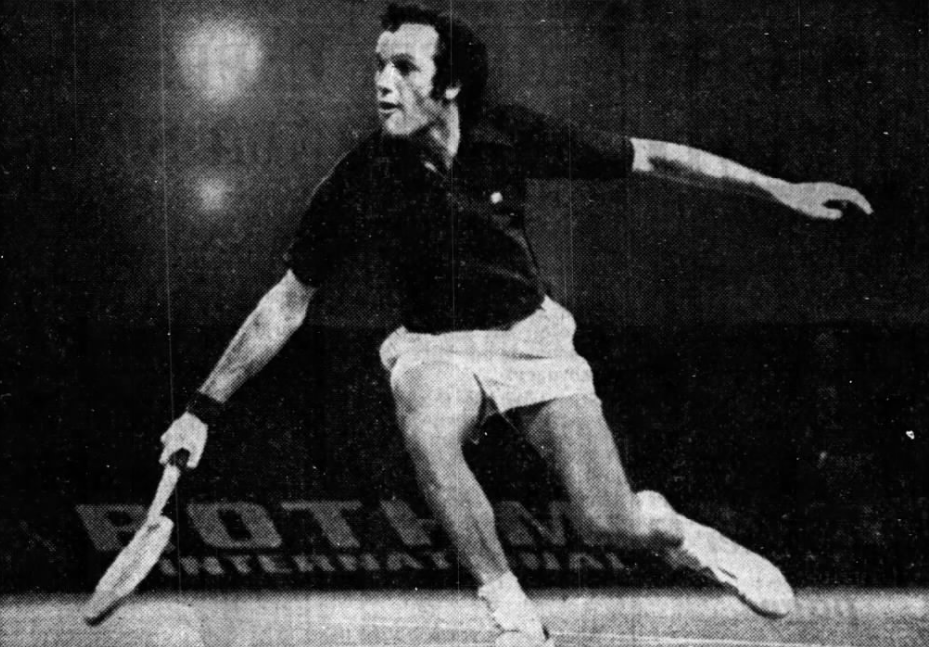

It wasn’t easy. Even though Evert hadn’t lost a set since Margaret Court beat her at the US Open and the Floridian won her first two matches in Jo’burg without the loss of a single game, Kloss came out fighting. Under the lights at Ellis Park, the left-handed Kloss pushed Evert behind the baseline and relentlessly attacked the net. She took the first set, 6-2, and after dropping the second, she grabbed an early break in the third. Only at 4-all in the third set did Evert find the form that had won her 84 matches and 10 titles since February. The American won 8 of the last 9 points to advance, 2-6, 6-3, 6-4.

Chrissie was officially the queen of 1973, even if her title came with an enormous asterisk. The dominant player of the season was Court, who won three of the four majors as well as just about every other tournament she entered. But most of those events were on the Slims circuit, while Evert and Goolagong piled up points on the weaker spring junket sponsored by the USLTA. Even without entering many of the Grand Prix-affiliated tournaments, Court finished third on the league table. Bonus money was contingent on participation, though, so the $12,500 third-place check went instead to Virginia Wade, and Court would have to settle for her existing season haul of just over $200,000.

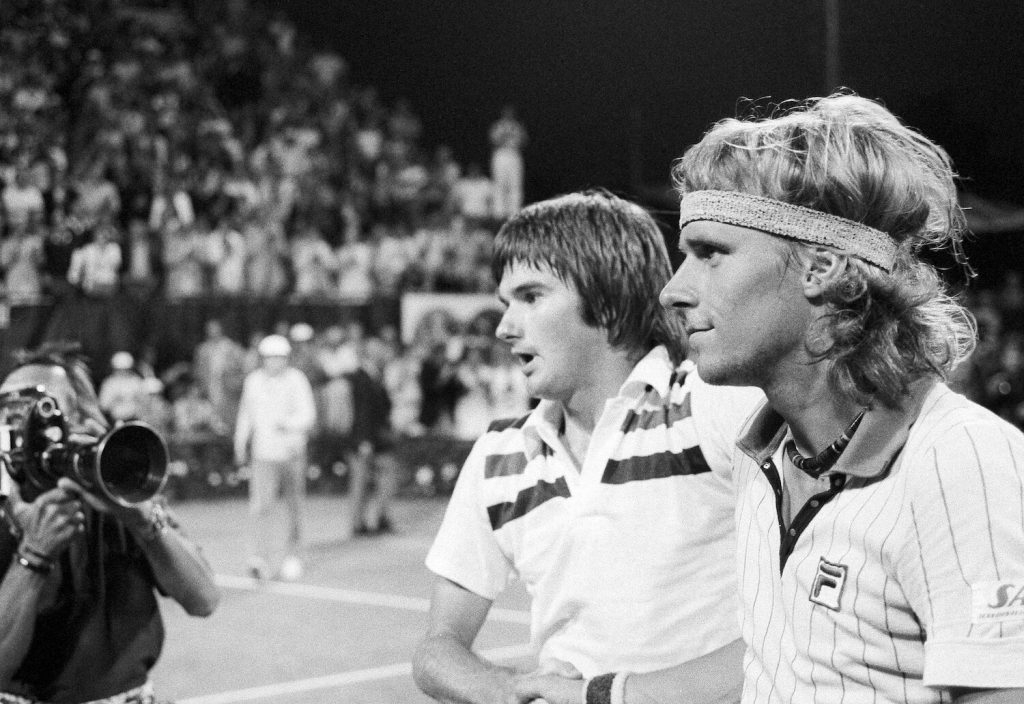

Still, Evert’s star was on the rise. She had reached two major finals, beaten Court at Wimbledon, and led the season series with Goolagong. Few would have questioned her status as the world’s top player on clay. Court and Billie Jean King wouldn’t be around forever, but promoters had little to worry about. With Chris and the wildly popular Evonne holding sway, the game was in good hands.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: