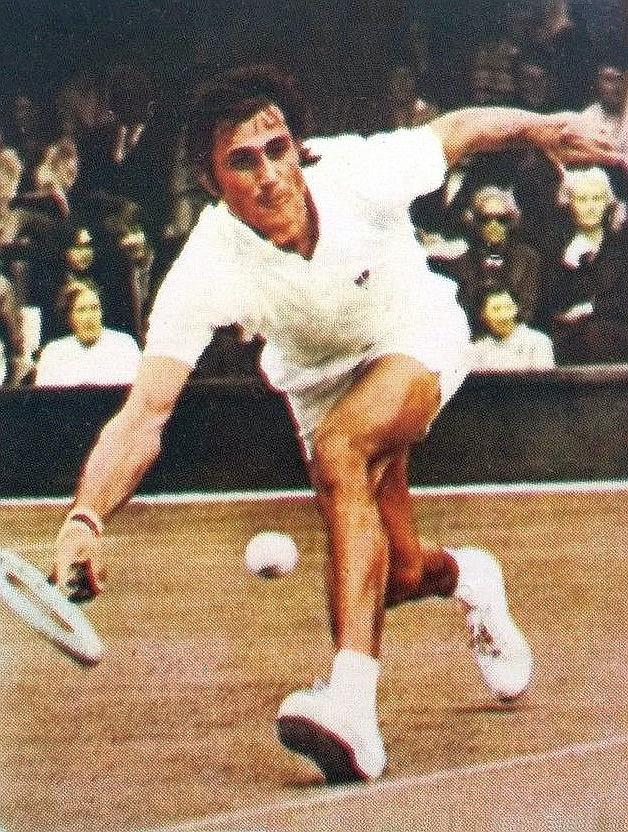

The knock on Arthur Ashe was always that he was erratic. At his best, he made flashy shots that no one else would even attempt. At his worst, those same shots would go wild, one after another. Early in his career, he lost a lot of matches when his focus betrayed him and he couldn’t recover in time.

Even at his most uneven, though, Ashe could usually hang in there. He owned a big serve, perhaps the most potent first strike on tour. When other shots betrayed him, he could reel off one ace after another and keep things close. Arthur won the 1968 US Open final on the back of a 14-12 first set. In a Davis Cup match a few weeks before that against Manolo Santana, two sets reached 11-all.

Arthur Ashe was not responsible for the introduction of the tiebreak, but he certainly played some sets that made fans wish for a quicker way of wrapping things up.

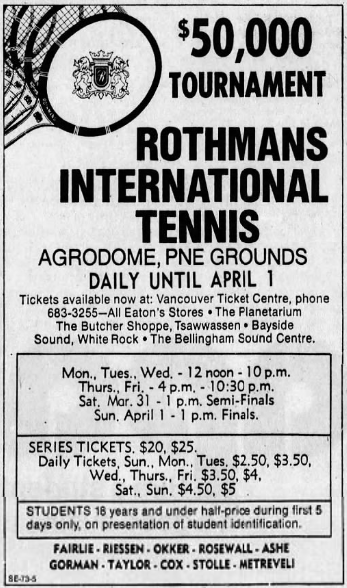

On April 4, 1973, Ashe met 21-year-old Roscoe Tanner in the second round of the World Championship Tennis event in Houston. Tanner was another cannonballer, the sort of opponent who would have guaranteed a marathon set or two against Ashe under traditional rules. But the WCT tour was all-in on the tiebreak.

In their best-of-three match, Ashe and Tanner didn’t play one tiebreak… they didn’t play two tiebreaks… they played three tiebreaks. Arthur earned a 5-2 lead in the first-set breaker, but Tanner charged back and took over, 10-8. The second set didn’t feature the same self-assured serving, and both men broke three times. But the end result was nearly the same. They reached a tiebreak, which Ashe won 7-2. The American pair deadlocked another 12 games before Ashe clinched his place in the quarter-finals with another 7-2 decision.

As far as I know, nobody counted aces. Safe to say there were a lot.

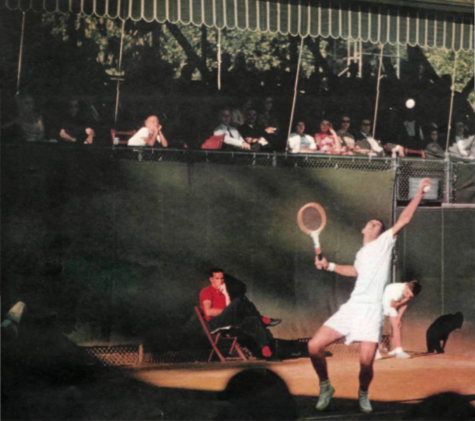

The oddest thing about the match, however, wasn’t the slim margin of victory. It was the crowd. Every single face in the gallery was a member at the River Oaks Country Club, the tournament venue.

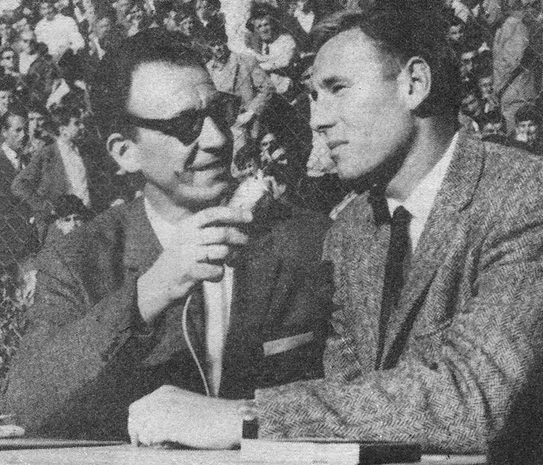

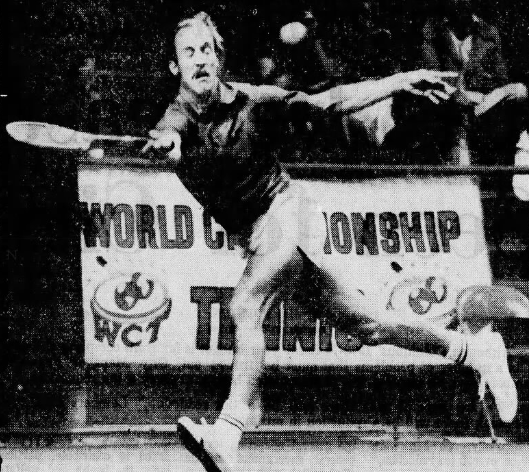

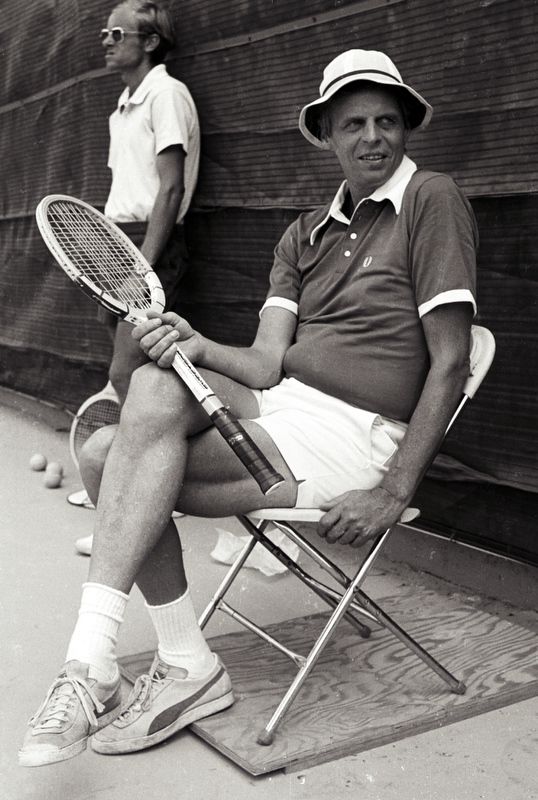

River Oaks had staged an event since 1931, when Ellsworth Vines won the inaugural title. It consistently attracted top American talent: Between 1931 and the end of the amateur era, eleven of the men in my Tennis 128 hoisted the trophy. Bobby Riggs won it in 1940. Rod Laver beat Roy Emerson for the title in both 1961 and 1962, and Laver came back as a pro to hold off Ken Rosewall in the 1972 final. The arrival of world-class tennis players was a highlight of the Houston social calendar, an annual tradition that survived into the Open era.

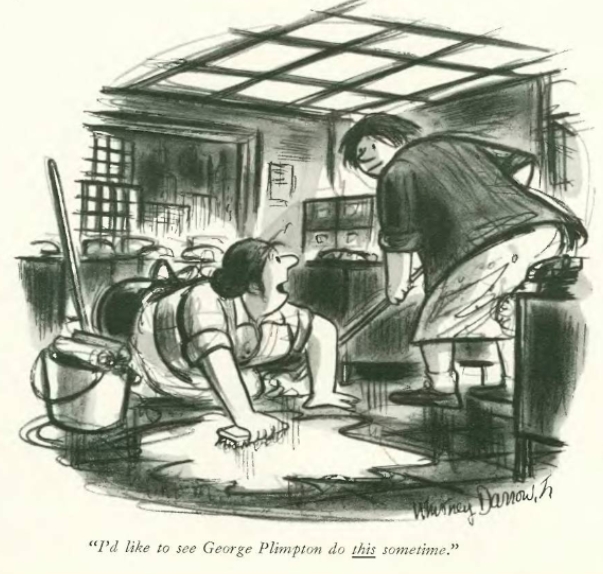

But in 1973, a change in the tax code prevented the non-profit River Oaks club from charging the public for admission. The club failed to find a workaround, funded the event itself, and held the matches behind closed doors.

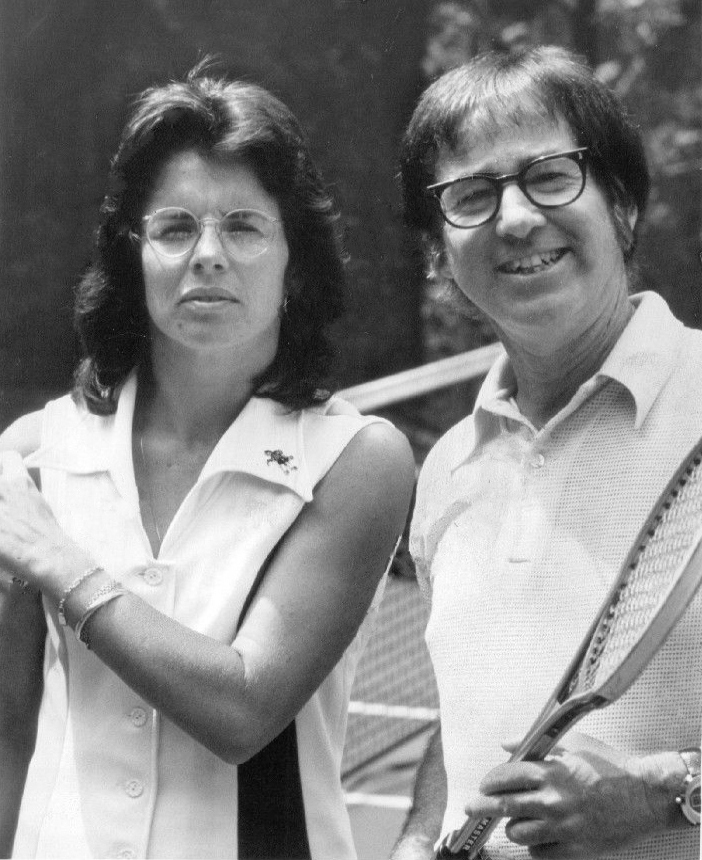

The players, understandably, didn’t like it. The tournament had long boasted the exclusive sobriquet of the River Oaks Invitational, but times had changed. This was the era of Open tennis, and that applied to fans as well. Ashe, who served as a kind of elder statesman among the pros through his role in the burgeoning players’ union, was the most outspoken of the group. “I don’t think the W.C.T. will play here [again],” he told reporters. “They’d be nuts if they did. They aren’t in the business of promoting closed tournaments.”

Ashe didn’t mention another offense, though many newspapers did. River Oaks was exclusionary on a full-time basis: The club had no Black or Jewish members. Arthur, however, picked his spots. He was more focused off the court than he was on it. In 1973, he fought harder for his fellow players than he did for racial justice. That would change over time, a shift accelerated by his November trip to apartheid South Africa.

Back in Houston, the closed doors of 1973 proved to be nothing more than a blip. River Oaks sorted out their tax issues and the public was welcome when the WCT troupe came through in 1974. In fact, they couldn’t have opened their doors any wider. When Laver returned and defeated Björn Borg in the final, he did so on national television.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: