By the time she was 19, Molly Hannas had been playing against boys and men for years. It wasn’t until she was 1973 that her story caromed off the zeitgeist.

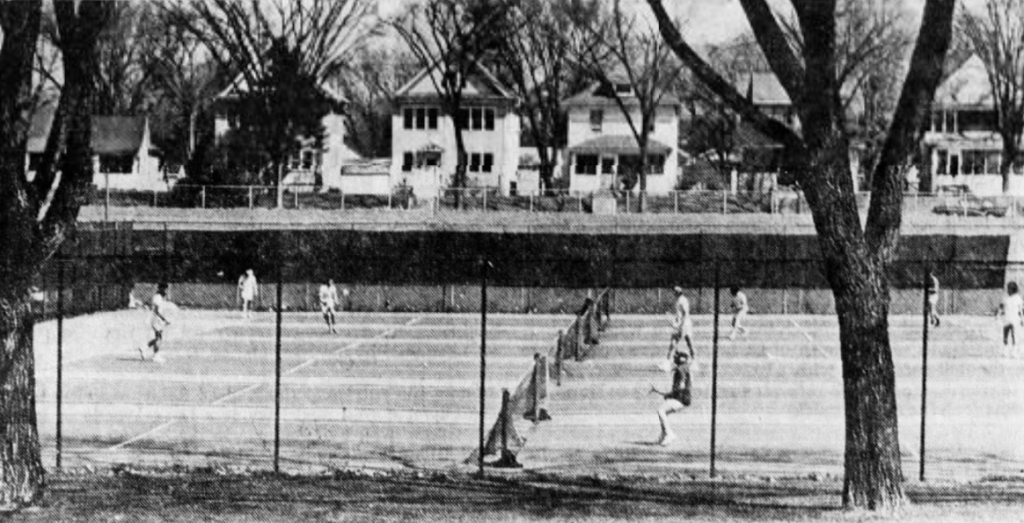

Hannas started her career playing high school tennis in Kansas City–on the boys’ team. She headed next to Purdue, competing against women and finishing runner-up in the Big Ten conference tournament. After a year, she transferred to Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. There was a women’s team there, but like at most institutions in 1973, it was nothing more than a club sport–an opportunity to get some practice with a part-time coach and play a few matches against local opponents.

Molly quickly got the lay of the land at Macalester and realized she could compete with anybody there, regardless of gender. The men’s coach, Jack Bachman, didn’t have any problem with her trying out for his team. She not only made the cut, she won the ladder competition and began the 1973 season as the squad’s number one player. Hannas’s first victim smashed his racket in frustration. Bachman kept the damaged stick as a souvenir.

In her own telling, Hannas wasn’t fighting any larger battle: She just wanted to play tennis. She assumed the same of the college boys across the net, and few of them treated her badly. Still, her success marked another tiny step on the road to gender equality in college sports. Title IX, the U.S. law that forbade sex-based discrimination at schools receiving federal funding, had passed in 1972. But no one had yet applied the law to athletics. Progress remained in the hands of one-off lawsuits and small-scale trailblazers like Molly.

The reputation of Macalester’s new star spread quickly. Bachman’s tally of broken rackets remained at one–it’s harder to get angry when you expect to lose. Hannas’s teammates were supportive–her doubles partner, John Molder, was especially complimentary–and competitors around the conference* learned that they needed to ignore her gender. “I thought I’d be embarrassed if I got beat,” said a vanquished rival from Bemidji State. “But I don’t. She’s just a real good player.”

* The best team in the Minnesota Intercollegiate Athletic Conference belonged to Gustavus Adolphus College, where the squad included a strong doubles player named Tim Butorac. Tim’s son Eric would star with the Gusties 30 years later, then go on to reach the Australian Open doubles final in 2014.

On April 27, Macalester’s season was winding down when the Associated Press sent Molly’s story out over the wire. She made the paper back at home in Kansas City. She even got a squib in the “People in Sports” column of the New York Times. The Times didn’t make an explicit connection to the upcoming Bobby Riggs–Margaret Court match, barely two weeks away, but no reader would’ve missed the link. It had been the biggest story in tennis for a month.

Hannas stayed focused on her local battles. “I like to think I play in Billie Jean King’s style,” she said. “But I’d never be able to match her.”

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: