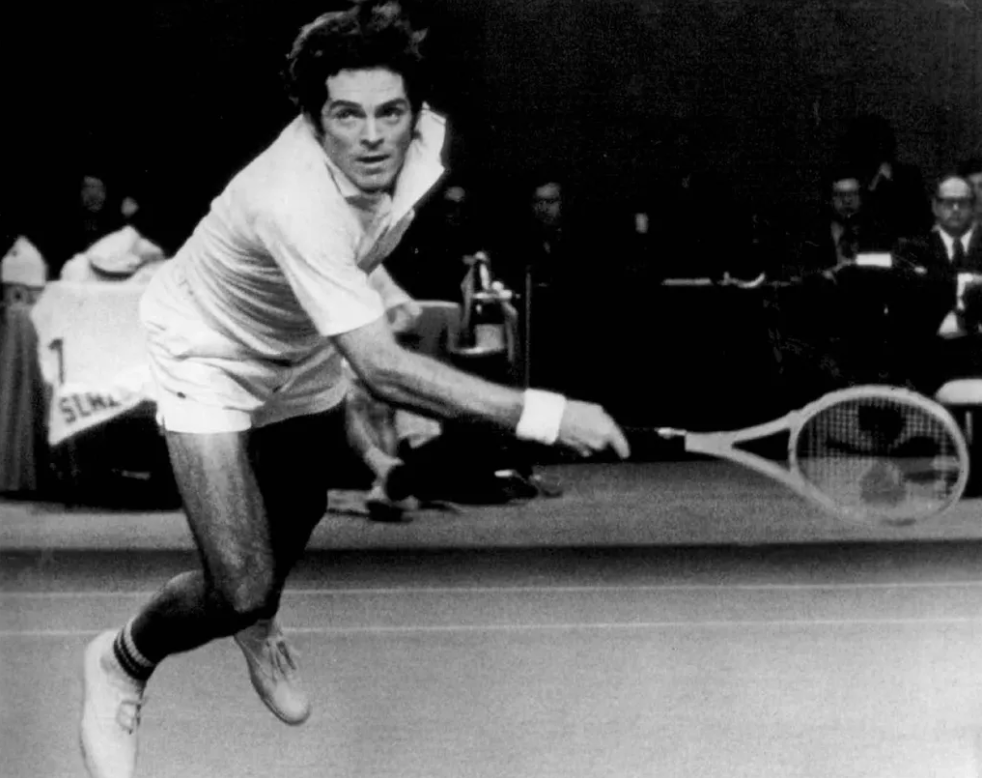

There was no single moment when the 1973 season officially ended and 1974 began. The tennis calendar was more of a perpetual cycle than a series of set campaigns. By the time Australia defeated the United States to reclaim the Davis Cup, preliminary ties in the 1974 competition were already in the books. When Ilie Năstase put the icing on his Grand Prix season with a victory at the elite Masters tournament, Australian Open warmups were in progress Down Under.

After the Australian Open, most of the world’s top players would head to North America, where the competing circuits had, for the most part, set aside their differences. Men would play World Championship Tennis and women would compete on the Virginia Slims tour. Unlike in 1973, Chris Evert would test her mettle against Billie Jean King, Rosie Casals, and the rest of the gang, and not just at the majors.

In the ongoing battle between tradition and made-for-television modernity, both sides tended to focus on money. Everyone’s bank balance looked better when the circuit headed for the biggest markets in the richest countries, especially if a TV network was interested in the rights. As the amateur ethic drifted further into the past, tournaments were less likely to be hosted at venerable clubs, more likely to be wedged into the calendar at arenas with artificial surfaces laid down a few days before the talent arrived. The traditionalists had fought for decades to preserve the old ways; now, their defeat was total.

One of the casualties was mixed doubles. What used to be a weekly feature was increasingly a novelty in a world where the tours rarely intersected. For 1963, my records include mixed doubles events at 215 tournaments around the world. A decade later, the number was down to 23, many of which were amateur events far off the beaten track of the major circuits.

The Riggs-King Battle of the Sexes symbolized a lot of things, perhaps none more than this: The genders now played against each other, not side by side.

* * *

That was not what Major Walter Clopton Wingfield had in mind.

In December 1973, the sport marked one hundred years since Major Wingfield first tried out “Sphairistiké,” the game he invented that would become known as lawn tennis. In 1873, Britain’s upper classes were mad for sports and games. Wingfield aimed to create a game that men and women could play together, more active than croquet and less vulnerable to a windy day than the newly faddish badminton.

As lawn tennis spread across the globe, many of Wingfield’s innovations, like his hourglass-shaped court, were set aside. But the notion of a mildly strenuous activity that mixed the genders was one of the keys to its success. Matches could be arranged in any conceivable permutation–Wingfield even imagined teams of three or four players on each side of the court–and competitors soon worked out ways to even the odds. Eighty-plus years before Riggs-King, early champions such as Blanche Bingley Hillyard and Lottie Dod competed against men, starting each game with a two- or three-point advantage.

Tournaments, back then, were social events, for players as much as for spectators. While mixed doubles was treated as a light-hearted pursuit compared to the more serious singles and men’s doubles, the most accomplished men and women usually took part. Fans loved it. It sometimes figured in courtships, as well: Even in the 1970s, the number of couples in the tennis world was a reminder of the amateur-era joint tournaments of the decade before. John Newcombe, Roy Emerson, and Cliff Drysdale all married veterans of the circuit. (It was also a small world: Emerson’s sister married Davis Cupper Mal Anderson, and Drysdale’s brother-in-law was doubles specialist and memoirist Gordon Forbes.) Even as opportunities dried up, the genders continued to mix: Stan Smith would soon wed Princeton standout Marjorie Gengler, and tabloid favorites Chris Evert and Jimmy Connors planned nuptials as well.

The new economics of tennis didn’t support old-school garden parties, and players of both genders eagerly made the sacrifice to chase after record prize money. Still, the public wanted mixed doubles, and promoters tried to give it to them.

* * *

A few days after Connors and Evonne Goolagong clinched titles at the 1974 Australian Open, a brand-new tennis concept appeared on North American televisions. Spalding sponsored the International Mixed Doubles Championship, an eight-team event with a prize pool of $60,000. The winning team would take home $20,000: ten grand apiece.

“Heterosexual tennis has come out of the closet,” cracked Bud Collins.

The event was a success, pleasing both players and fans at the Moody Coliseum in Dallas, Texas. King and her usual mixed partner, Owen Davidson, took first place with a best-of-five-set victory over Casals and Marty Riessen. Simply reaching the final was an achievement: Other names in the field included Rod Laver, Nancy Richey, and doubles whiz Françoise Dürr.

(Laver wasn’t known as a mixed expert, but between 1959 and 1962, he won three majors and another six titles with Darlene Hard. Her first words to the untested youngster: “I’ll serve first and take the overheads.”)

“I loved to play mixed,” King said. “The millions of ordinary players, the hackers, can relate with mixed–or any kind of doubles–because that’s mainly what they play. Often mixed is a lot more interesting and exciting for spectators than singles. The ball’s in action more. The attendance at this tournament, and the TV prove there’s a market for mixed.”

It wasn’t just Spalding that was willing to make that bet. World Team Tennis, slated to begin play in May 1974, was built on the same premise. Each squad would feature both men and women, and doubles matches–included mixed–would have as much weight as one-on-one competition. When the Minnesota Buckskins faced the Philadelphia Freedoms, Davidson, player-coach for Minnesota, would find himself in an unfamiliar and unenviable position: across the net from Freedoms star Billie Jean.

Major Wingfield would barely have known his own invention in the tennis world of 1974. The courts had straightened out, the nets had come down, and rackets had evolved beyond recognition. The sport featured millionaire players, tournaments on six continents, and a 55-year-old man who walked like a duck but had somehow captivated a nation. Still, Wingfield would have picked out glimmers of what made lawn tennis a 19th-century sensation: Men and women playing alongside one another, joking, bickering, and–every once in a while–falling in love.

* * *

This post concludes my 128-part series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Read the whole thing by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows the full Table of Contents.

In 2024, I’ll be writing regularly about analytics and contemporary tennis, with some history thrown in. Subscribe to receive each new post by email: