Credit: Michael Erhardsson

In 2022, I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. With luck, we’ll get to #1 in December. Enjoy!

* * *

Stefan Edberg [SWE]Born: 19 January 1966

Career: 1983-96

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1990)

Peak Elo rating: 2,239 (1st place, 1990)

Major singles titles: 6

Total singles titles: 41

* * *

No one ever knew quite what to make of Stefan Edberg. When he burst out on the international scene by winning the 1985 Australian Open at the age of 19, he was called a machine, a robot. He was unfailingly polite, as he always would be. But he didn’t give the press much to go on.

“Stefan doesn’t say much, even for a Swede,” according to his more voluble countryman, Mats Wilander.

He didn’t smile much, either. That was what many fans noticed when he upset world number one Ivan Lendl in the Melbourne semi-finals. Lendl’s stolid on-court demeanor was old hat. But they expected more personality from a teenager, especially after witnessing Boris Becker’s jubilant victory at Wimbledon earlier that year.

He could also verge on the heartless. Edberg said in 1986, “For sure, I’m disappointed, but there is always a tournament next week.” That was after losing in the third round at Wimbledon. Ho hum. The following year at the Championships, he beat Stefan Eriksson, 6-0, 6-0, 6-0.

Personality or no, the Swede’s serve-and-volley game steadily gained admirers. He did all the talking he needed to do with his racket. Fellow player Horst Skoff said, “Stefan has the grace of a ballet dancer.”

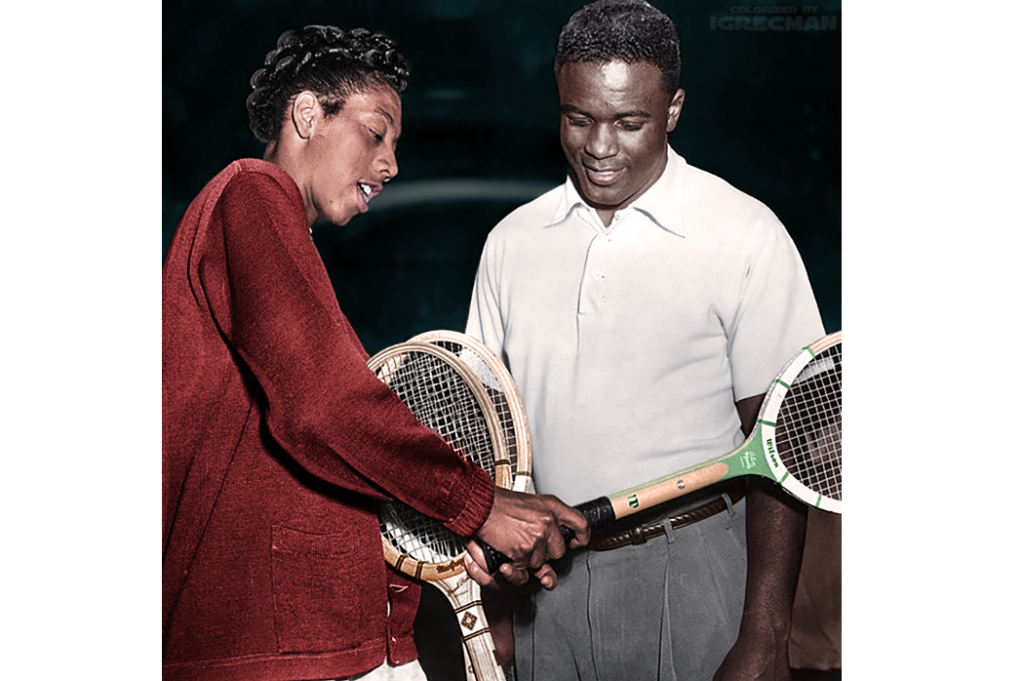

Edberg at Wimbledon in 1987

Alison Muscatine wrote in the Washington Post: “There is nothing more beautiful or more breathtaking than Stefan Edberg’s tennis game when he is on. Every stroke is poetic, every movement lyrical.”

By 1991, Edberg was number one in the world. He remained a closed book, but journalists chronicling the Hollywood life of Andre Agassi were coming to appreciate that. After the US Open, Sports Illustrated summed him up as “a quiet, tough and admirably swell fellow.” A year later, he defended his title in New York with a series of dramatic victories, even showing the occasional flash of emotion on court. It was unanimous: Stefan was definitely human.

Edberg was an introvert, certainly. He liked things organized. He was easily overshadowed by Becker’s flashiness or the late-career showmanship of Jimmy Connors. No matter. For him, the object was to win tennis matches with a minimum of fuss–no more, no less.

The word that reporters spent a decade looking for, the one adjective that summed up the Swede and his tennis, was efficient.

* * *

“I play tennis the simple way,” Edberg told the journalist Franz Lidz in 1991. “Don’t wait for the other guy to make mistakes–just outplay him and finish the point off yourself. Try not to make tennis too difficult: It’s difficult enough. Don’t complicate it: Just hit the ball where the opponent is not.”

Ah, so that’s what I’ve been doing wrong all these years.

Tennis was so simple for Edberg that he was sometimes accused of lacking a brain entirely. Two months after his 18th birthday, he picked up his first tour title with a straight-set victory over Wilander in Milan. The veteran never got a good read on the newcomer’s serve, and he admired Stefan’s second-serve kicker so much that he tried to add it to his own game. After the match, he delivered a whopper of a backhanded compliment:

When I was coming up, Björn Borg told me I could become one of the best players in the world because I used my mind when I play. With his serve, Edberg can play without thinking.

Edberg might not have possessed a tennis brain equal to Wilander’s. Few players did. Still, he was hardly just taking his whacks and hoping for the best.

The young Swede recognized that charging the net was a gamble. He knew that some of his serves would come back too hard. Some passing shots would find the line. But he also learned that he could stack the deck in his favor.

It’s a misleading platitude that tennis is like chess; for one thing, serve-and-volleyers rarely need to think more than one or two moves ahead. Edberg liked the metaphor anyway, and he thought about his own game in those terms. No less an expert than Russian chess great–and tennis fan–Anatoly Karpov concurred. “I play positional chess,” said Karpov. “He plays positional tennis.”

* * *

Even in the 1980s, Edberg’s particular brand of serve-and-volley tennis was something of a throwback. While his serve–especially the high-bouncing second serve–was strong, it was far short of the devastating deliveries wielded by Becker and, later, Pete Sampras.

The few players today who come in behind their serves tend to be the men with the biggest first-strike weapons. The move forward functions as a kind of final sweep. If, somehow, the ball comes back, it’s an easy putaway. That trend was already in evidence by the midway point of Edberg’s career. Men like Goran Ivanišević, Michael Stich, and even Becker could expect that most of their trips to the net would be purely ceremonial.

Edberg serving in 1989

The Swede was different. Like the stars of earlier eras whose serves were limited by primitive equipment and strict foot-fault rules, he used the serve to set up a first, or even second volley. It’s the tactic that he encouraged in Roger Federer, and one that we occasionally see now from Carlos Alcaraz.

We can look at the data compiled by the Match Charting Project to get a sense of how Edberg differed from the best of his serve-and-volleying peers.* In the matches logged by the project, 71% of his serves came back. That’s a solid service performance, but returners had a much harder time against Becker (65%) and Sampras (62%).

* These figures are not official, because the Match Charting Project hasn’t logged anywhere close to every match from this era. In addition, the sample is not random. We’re more likely to have high-profile matches–finals, semi-finals, meetings between elite players–than others, so each man’s true career averages are probably more impressive than the numbers I give here. That said, the biases in the dataset should be roughly the same for all three men, and the stats are based on many thousands of points for each player. We’ve charted 159 Edberg matches, 107 of Becker’s, and 163 involving Sampras.

As soon as Edberg struck his second shot, his numbers edged into elite territory. He won 46% of his total service points with his first or second strike. Becker was only marginally better (47%), and Sampras’s advantage (at 52%) was much smaller than his lead in the unreturned serve category.

When we look specifically at the serves that came back, the gap almost disappears. Edberg won the point 51% of the time that the returner put the ball in play. Becker managed 50%, and Sampras narrowly led the trio at 52%. Opponents may have felt they had a better chance against the Edberg serve, but their optimism was only fleeting.

* * *

It was unfair to suggest that Stefan played without thinking. But there was a grain of truth there. The game did come extremely easily to him. By his early teens, he had developed the signature service motion that later became part of the logo for the Australian Open.

He was also a quick study. His first coach, Percy Rosberg, saw him knife one backhand volley after another and suggested that Stefan trade in his double-handed backhand for a one-hander more akin to his graceful stroke at the net. It was a gamble for an established junior star–he had already won the European Junior Championships–but it barely slowed his progress.

(The advice also makes Rosberg one of the more underrated gurus in modern tennis. A decade earlier, he told a young Borg to ignore the skeptics and stick with his own two-handed backhand.)

Rosberg didn’t like the life of a traveling coach, so Edberg began a career-long relationship with former British Davis Cupper Tony Pickard. Taking over after Stefan’s standout 1984 campaign, Pickard saw only two things missing from the 18-year-old’s game. He needed to improve his body language on court. And to extract the most out of his serve-and-volley strategy, he needed to get faster.

Edberg’s tendency to get down on himself contributed to the generally morose atmosphere in that 1985 Australian Open semi-final with Lendl. Pickard was convinced that the sulking not only gave too much information to opponents, it also directly affected the play of his young charge. In those first few years, the result was to make Edberg seem even more robotic. If he didn’t reveal any negative emotions during matches, he didn’t show any emotion at all.

* * *

The second Pickard project is what inspired all those ballet metaphors. Footspeed isn’t the only ingredient in a successful serve-and-volley attack, but it sure helps.

The difference between Edberg’s service and (for instance) Becker’s more powerful deliveries gave the Swede a tiny bit of extra time to assume a threatening position at the net. As he got faster, opponents couldn’t return the ball and track his location simultaneously. They could only assume he was close, and they were usually right.

By 1991, Edberg had won four majors, and Pickard considered his task accomplished. “Now Stefan moves like a gazelle,” he told Sports Illustrated. “Sometimes he seems to be floating. It’s almost mystical.” Veteran sportswriters had it easy when Roger Federer came along. They could describe the young Fed with the same fawning phrases they had used for Edberg a decade earlier.

The Swede won the US Open that year with a near-perfect performance in the final against Jim Courier. In 1992, he defended the title–barely. It took three straight five-setters, including one of the monumental encounters in tournament history, a semi-final against Michael Chang. Chang was one of the few men on tour with the timing–not to mention the chutzpah–to take Edberg’s serve on the rise, so matches with the American were never easy. In this one, the Swede rushed the net 258 times in 404 points. After five and a half hours, Edberg advanced, 6-7, 7-5, 7-6, 5-7, 6-4.

The final was a cakewalk by comparison. Edberg was exhausted, but so was his opponent, Pete Sampras. Sampras was sick, too. This one took only four sets, and at age 26, Edberg had his sixth major title.

* * *

Early in his career, Stefan once practiced with Jimmy Connors. Connors was famous for his short, intense sessions. He told the Swede that it was only worth playing if you could give 100%. To reach that level in matches, you needed to practice that way, too.

Edberg later said it was the best advice he ever received. He certainly took it seriously. Injuries crept in–Percy Rosberg had predicted back injuries the moment he saw young Stefan’s kick serve–and when the champion couldn’t maintain a high level of form, he didn’t drag things out. He played a competent full season in 1996 and called it quits.

Even in retirement, he keeps Jimbo’s advice in mind. Edberg has taken part in his share of senior events, but he prefers not to play too many. He’s not that interested in competing when he’s not at his best, and he knows the physical demands of reaching that level. Instead, he took up squash, quickly becoming one of the best players in Sweden.

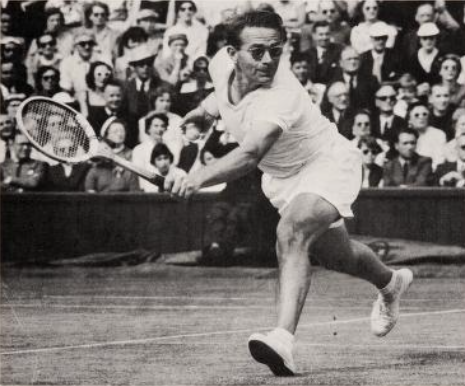

Edberg (right) with Federer at Wimbledon in 2014

And, of course, the graceful netrusher spent two years coaching Roger Federer.

Mats Wilander remains one of Edberg’s most frequent on-court foes. In a broadcast interview, Wilander asked Federer, “What have you told him about his forehand? It’s become a fatal weapon now. I have no chance anymore, that used to be his weak side.”

“You’re right,” Federer joked. “I didn’t call up Stefan to ask him to be my new coach. Stefan called me because he wanted to start working on his forehand in his old age. He said he was willing to pay anything for my advice. So, we work on it daily, and he travels with me wherever I play.”

We all laughed. But during his playing career, Edberg rarely let such a prime opportunity get away. Are you sure you’d put it past him?