I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. Beware of GOATs.

* * *

Pete Sampras [USA]Born: 12 August 1971

Career: 1988-2002

Plays: Right-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1993)

Peak Elo rating: 2,319 (1st place, 1994)

Major singles titles: 14

Total singles titles: 64

* * *

Pete Sampras played over 500 tiebreaks in his career. His record over 15 years at tour level was 328-194, a 62.8% winning percentage.

Sounds pretty good, right? I don’t expect you to know exactly how 62.8% rates among the game’s best. It’s one of the many tennis stats that sounds like it might be great, but it might also be the sort of thing that strong players do as a matter of course.

In fact, 62.8% rates fifth among all players in the Open era. Only Roger Federer, Arthur Ashe, Novak Djokovic, and, puzzlingly, Andrés Gómez did better. Now that we know Pete scores in the top five, we can pretend that it was obvious all along. One of the biggest serves of his (or any) era, plus imperturbability under pressure–what more could you need?

Forgive me as we dive straight into the weeds here. Tiebreak success isn’t as simple as it sounds. Yes, Pete and Fed (and the others) were great at the end of sets, but they were great the rest of the time, too. The win-loss percentage simply confirms that they were very good at tennis, not that they raised their games at 6-all.

A decade ago*, I introduced a stat called Tiebreaks Over Expectations (TBOE) to address the less obvious aspect of tiebreak success. We can take a player’s serve and return performance over an entire match and calculate the odds that he would win a tiebreak. Do that for all of his tiebreaks over an entire season, or a full career, and you can figure out how that won-loss percentage compares to his overall performance.

* Yikes.

What may surprise you is that most players converge on a TBOE of zero. Conventional wisdom says that big servers have an edge in tiebreaks. Nope. Apart from the self-evident fact that better players tend to win more breakers, it’s a coin flip. The only minor exception is that men who contest lots of tiebreaks–big servers or not–do a tiny bit better. Experience may count for something, but the effect is barely enough to register.

A few specific players manage to break the mold. When we rank ATPers of the last thirty years by TBOE, Sampras edges up to third place. John Isner leads the list by a wide margin: He plays tiebreaks constantly and ups his level when he gets there. Federer comes next.

Had Sampras played as well at 6-all as he did in the first twelve games of the set, his career record in shootouts would’ve been 299-223, a respectable but hardly newsworthy rate of 57.3%. Instead, he outperformed expectations by 29 tiebreaks. That might be luck, tactical soundness, or ice-cold water where the blood is supposed to go. Even if we can’t pin down the details, it’s clear that he was doing something right.

* * *

Pete got smarter throughout the 1990s. Tim Gullikson and, later, Paul Annacone taught him to use his range of weapons to play percentage tennis. While he never became as single-minded as, say, Jack Kramer in pursuit of that goal, it was clear that he learned to outthink his opponents, not just outsmoke them.

Sampras didn’t have much to say about tiebreaks in his 2008 memoir, A Champion’s Mind. He recognized that luck often dictated the outcome of such close sets, especially on fast courts. If he holds any secrets (besides “don’t choke!”) he isn’t telling.

Opponents learned that Pete was at his strongest at the tail end of a set. Mats Wilander told Steve Flink that Sampras “had a lot of guts in big time moments.” Wilander also noticed that Pete made sure his opponent would be off-balance when the crucial moment arrived. Over the course of a set, he would alternately push hard, relax, keep points short, force you into a rally–anything to prevent the man across the net from getting into a rhythm. For a player like the Swede, that was deadly.

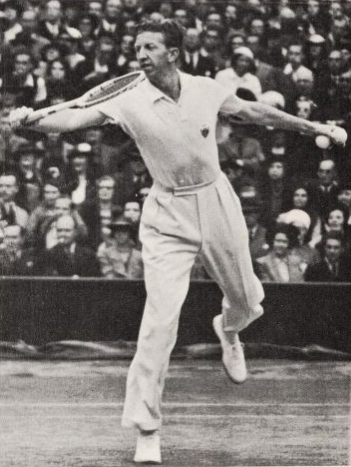

The Sampras serve in 1991

Pete knew better than anyone that a match could hinge on just a few turning points. “To me,” he wrote, “a match with a lot of service breaks is as unsatisfying as a match with none, because a great match is only supposed to have a handful of decisive moments.” He aimed to be ready for those opportunities.

For Sampras, that’s the difference between an all-time great and the rest. He noted in his memoir that more “one-slam wonders” have broken through at Roland Garros than at Wimbledon. Men like Boris Becker, Stefan Edberg, and himself often squeaked through by the smallest of margins, but the narrow scorelines were deceiving.

Jim Courier, who lost to Pete 16 times in 20 meetings, could only nod in agreement. “You wonder what the heck just happened because you thought you had been outplaying him,” Courier told Flink. “That is what playing Pete felt like because he could summon his greatness late in a set. He just had that knack.”

* * *

Far be it from me to question the wisdom of Sampras, Courier, and the rest, but I find these sorts of explanations unsatisfying. The closer we get to the top end of the Tennis 128, the more we see champions described in nebulous terms. They were intimidating, mentally overpowering, cool under pressure. Maybe it’s true, but they must have been doing something, too.

Back into the weeds we go.

The Match Charting Project has logged 163 Sampras matches, which include 116 of his career tiebreaks. It’s a not a random sample; for our purposes, it’s even better. We’ve recorded every point from the most prominent matches–grand slam and Masters finals and semi-finals, head-to-heads with Andre Agassi, and so on. The dataset offers us a fairly complete look at how Pete played when the outcome really mattered.

Compared to his performance in the twelve games leading up to each tiebreak, Sampras did everything better in the breaker. He put 1% more first serves in. He won 1.3% more of his service points. 1.3% more of his serves didn’t come back. He even won return points at a better clip, though by the minuscule margin of 0.4%.

Small as these numbers are, keep in mind that they represent improvements on already strong statistics. Pete amassed them when his opponents cranked their own games up as far as they could go. Consider also that they dispel a common notion that may be true of more one-dimensional big servers. Sampras may have taken it easy on some unimportant return points early in sets. But his tiebreak magic derived more from upping his game on serve than return.

What’s more, a 1% improvement on serve is massive compared to the performance of the average tour player. The Match Charting Project doesn’t have a wide base of 1990s matches from which to infer tour averages, but we can assume that this part of the game didn’t change much in two decades. Using charts from the 2010s, I found that in the typical tiebreak, returners win 6.5% more points than they had in the twelve preceding games. Virtually every contemporary player of note sees their serve numbers decline in breakers.

Not Pete. He recognized that the luck of the tiebreak could go against him, but he also knew that luck favors the elite server playing the smartest percentages.

To see Sampras’s steeliness under pressure, look no further than the fifth-set buster against Alex Corretja in the 1996 US Open quarter-finals. At 6-7, Pete saved match point with a forehand volley winner. After missing his first serve at 7-all, he went big with his second, caught the Spaniard leaning the wrong way, and scored an ace. Corretja–who, incidentally, retired with a 51% career tiebreak winning percentage–double-faulted to end the match.

They didn’t call him Pistol Pete for nothing.

* * *

The irony of all this tiebreak talk is that Sampras’s career results hardly rely on a pile of clutch breakers.

Of the 14 major finals that he won, perhaps two can be scored as direct results of his tiebreak prowess. Pete beat Courier in 1993 for his first Wimbledon title, 7-6, 7-6, 3-6, 6-3. His second Wimbledon crown also involved two shootouts. In 1994, he blasted past Goran Ivanišević 7-6, 7-6, 6-0.

In two later Wimbledon finals, the luck of the tiebreak evened out. Sampras and Ivanišević played a five-setter to determine the 1998 championship, each winning a breaker in the first two sets. The title match in 2000, against Pat Rafter, started the same way. The Australian–owner of a pedestrian 54% career tiebreak mark–took the first set in a 12-10 shootout only to see Pete win the next one.

For Pete’s opponents, the threat of the tiebreak was more daunting than the event itself.

Courier won 9 of the 17 breakers the two men contested. But more often, he didn’t make it that far. Pete “wouldn’t be bothered by not playing well in your service games,” he said, “because he would just keep holding serve.”

It was a walk in the park for Sampras, while the pressure kept building on the man trying to break him. Pete likened grass-court tennis to “an old-fashioned Western gunfight,” and he was rarely the one to blink first. Whether it was his own ability to raise his game or the pressure he put on opponents, he converted break points more often than he won other return points, just as he exceeded expectations in tiebreaks. His outstanding performance in breakers may have made only a modest impact on his career records, but it indicates how he was able to play his best tennis at just the right times.

* * *

All these numbers have a way of making the man sound colorless, and that was indeed the knock on Sampras for much of his career. He was shy, and he wasn’t equipped to handle the pressure or media attention when he won the 1990 US Open at age 19.

His tennis could be electrifying–especially if you liked your points short–but even as he matured, he left the tabloid headlines for Agassi.

Over the years, though, it became clear that his desire to compete was every bit the equal of more demonstrative Americans like Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe. In the 1996 match against Corretja, he became so dehydrated that he vomited between points of the fifth-set tiebreak. Tournament officials hooked him up to an IV after the match, and McEnroe told Pete’s girlfriend, “I don’t have that much guts.”

It wasn’t just one marathon match. By the time he outlasted Corretja, Sampras had gutted out nearly two years of his career. At the 1995 Australian Open, his coach and close friend Tim Gullikson collapsed from a seizure, the latest in a months-long string of health scares. He was soon diagnosed with brain cancer. Pete defeated Courier in the quarter-finals of that tournament with tears in his eyes. Gullikson battled the disease for another 16 months before succumbing. He was never far from Pete’s thoughts.

It was particularly difficult for Sampras to push aside his concern for his ailing coach when he played Davis Cup. The American side was led by Tim’s twin brother Tom. Pete’s exploits at the 1995 Davis Cup final made clear what he was capable of when his will to win was fully engaged.

The tie was held in Moscow, where the Russians laid down a glacially slow court designed to flummox the visiting Americans–the clay-phobic world number one in particular. Initially, the team planned to use Agassi and Courier in the singles. But when Andre pulled up lame, Sampras was forced into action on his weakest surface.

After a marathon five-setter against Andrei Chesnokov, Pete collapsed on the court from cramps–but he won. Leigh Montville wrote for Sports Illustrated that it “looked as if he might not play again for a long while.”

Yet the next day, he was back on court for the doubles. Yevgeny Kafelnikov was so dismissive of Sampras’s skills in the tandem game that he said the Americans had given the match away. “I guess they don’t know Pete,” Captain Gullikson said. “I would take him on my side for one-on-one tennis, two-on-two, three-on-three, any surface. I would take him for golf.”

Kafelnikov played six sets against Pete–three in doubles, and three in singles–and didn’t win a single one. On a surface chosen in large part to thwart him, Sampras won three rubbers to secure the 1995 Davis Cup for the Americans.

The higher the stakes, the more reliable Pistol Pete became. His typical attack was vicious enough to quickly dispatch most of his peers. When it wasn’t enough, Sampras was the one who could find another level.

When that wasn’t enough, it came down to sheer desire, a willingness to put his body on the line. Most opponents never learned how deep Pete was willing to dig. Push him to the brink, though, and they discovered that there was no limit to the amount of pressure he could handle. Sampras didn’t win every close match he ever played, but he never gave one away.