I’m counting down the 128 best players of the last century. Separation anxiety is starting to set in…

* * *

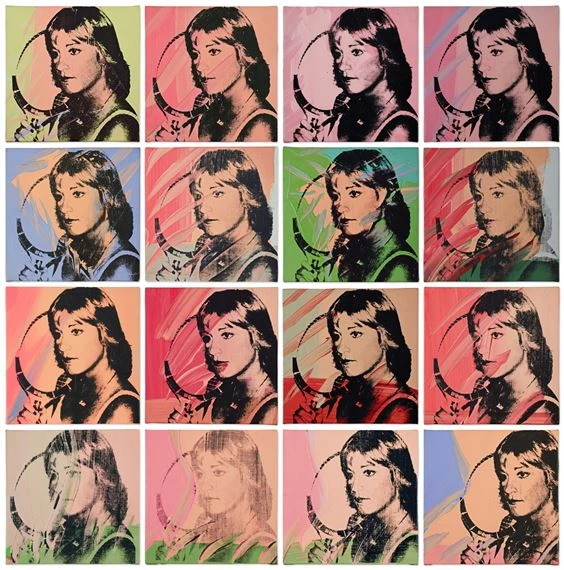

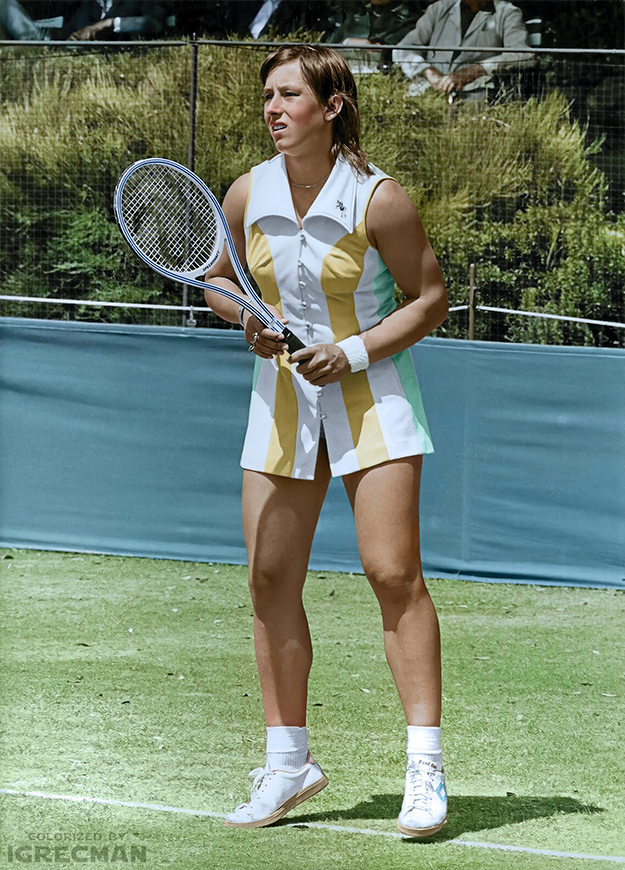

Martina Navratilova [CZE/USA]Born: 18 October 1956

Career: 1973-94 (doubles to 2006)

Plays: Left-handed (one-handed backhand)

Peak rank: 1 (1978)

Peak Elo rating: 2,575 (1st place, 1984)

Major singles titles: 18

Total singles titles: 167

* * *

On Monday, it rained.

On Tuesday, it rained.

Wednesday, Thursday, you get the idea … it rained every single day of the first week of the 1985 Wimbledon Championships. It wasn’t a total washout; the singles events remained nearly on schedule. With women like Martina Navratilova and Chris Evert atop the field–they were co-number one seeds this year–the sky didn’t need to clear for long. Martina’s victories were so certain that news reports were more likely to emphasize how quickly she got off the court.

Two years earlier, Navratilova averaged just 47 minutes per round as she won her fourth Wimbledon title. Andrea Jaeger was so aware of the clock that when she lost the first set of the final to Martina in 17 minutes, she considered stalling to salvage a little bit of dignity.

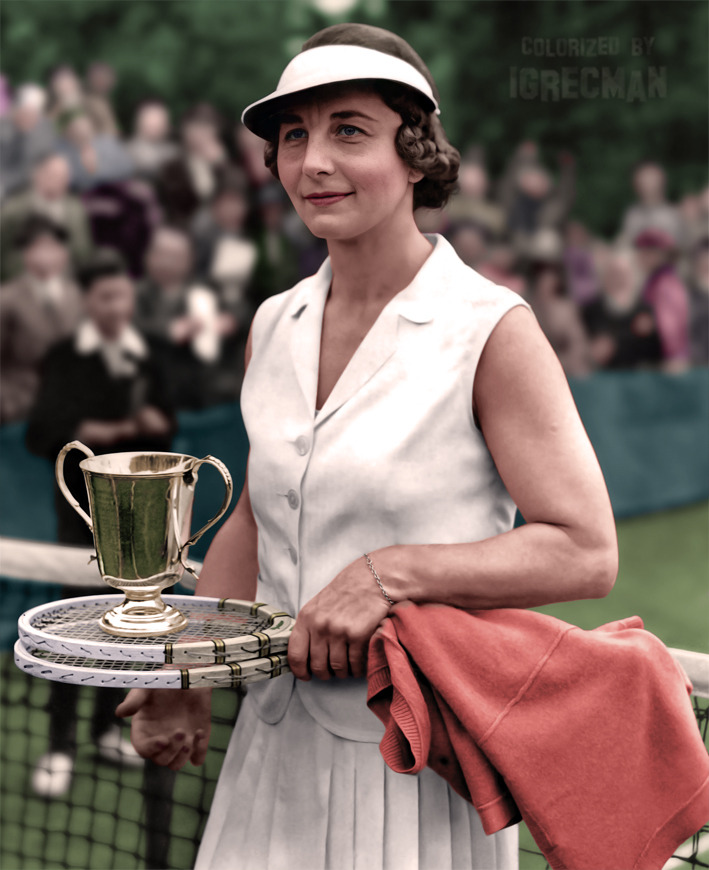

In 1985, Navratilova was gunning for her sixth Wimbledon crown, her fourth in a row. No one had done that for 55 years, since Helen Wills. Martina was always the favorite on grass, her athletic serve-and-volleying game a perfect fit for the surface. But Evert was a renewed threat. While Navratilova had won 19 of their last 24 meetings, one of the losses was the French Open final a month before. Chrissie was playing so well that she had retaken the number one WTA ranking. Only the idiosyncrasies of the All-England Club kept a 1 next to the defending champion’s name in the draw.

Martina’s other problem was that her schedule was about to get very busy. To fit all the singles matches into the first week, the tournament had postponed most of the doubles. Navratilova was entered in women’s and mixed doubles, so if she reached all three finals, she’d have as many as sixteen matches to play in the second week.

Spoiler alert: She made all three finals.

Navratilova got past her long-suffering doubles partner, Pam Shriver in the quarter-finals, Pam’s 24th loss in their 27 meetings to that point. (She’d lose 17 more.) Their chemistry on the doubles court was, as always, unaffected. In the doubles round of eight, the pair straight-setted Evert and Jo Durie. It was Navratilova and Shriver’s 108th straight victory as a team, a streak going back two years.

On Saturday, the women’s singles final was Martina’s 11th match in six days. Evert played nearly perfectly in the first set, making only three unforced errors and taking the opener, 6-4. But Navratilova settled her nerves and resumed her world-beating grass-court form. That day–okay, that entire year–she played some of the best serve-and-volley tennis in the game’s history. Chipping returns on the grass, she could come in on Chrissie’s serve, too. She allowed only two break points in the final two sets. With a 6-3, 6-2 finish, she improved her career record against Evert to 34-32.

Fatigue finally set in for the women’s doubles final, played the same afternoon. Navratilova and Shriver fell in three sets to Kathy Jordan and Elizabeth Smylie. The doubles streak ended at 109.

But the tournament did not end on a down note for the 28-year-old Czech-American. On Sunday morning, she had still yet to start her mixed doubles quarter-final. She and Paul McNamee played nearly six hours of tennis, including a 23-21 deciding set in the semi-finals. For the title, Navratilova and McNamee beat the Australian team of Smylie and John Fitzgerald in another three-setter, capping a 99-game day.

Navratilova later admitted to her biographer, Johnette Howard, what she sometimes wondered. She was speaking more generally, but it sure fits that week at Wimbledon: “How did I ever do it?”

* * *

If it weren’t for that madcap final week, the 1985 Championships would barely register as a notable moment in Navratilova’s career. It was her sixth of nine singles trophies at Wimbledon, her 12th of 18 major titles overall. It was one of 37 career major finals in women’s doubles and one of ten mixed doubles championships.

The end result was certainly not a surprise. 1985 was the fourth season of an exceptional five-year run in which Martina lost only 14 singles matches. Total. She won 74 straight in 1984. From the end of 1982 through the 1984 US Open, she beat Evert 14 times in a row.

A reporter asked Chrissie if she thought anyone else even had a chance against Navratilova. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I don’t.”

“You know exactly what she’s going to do,” said Arthur Ashe, “but there isn’t a thing you can do about it.”

No one had ever doubted Martina’s athleticism. She won her first tour event in 1974, when she was 17. Her big left-handed serve, combined with flashy footspeed and an acrobatic net game, got her past veterans Rosie Casals, Françoise Dürr, and Julie Heldman in succession. A few months later, she reached her first major final, upsetting Margaret Court in the Australian quarter-finals before falling short against Evonne Goolagong in the final.

Colorization credit: Women’s Tennis Colorizations

The same year, Billie Jean King told the teenager just what she was capable of. “You know,” said the Old Lady, “you could be the greatest player ever.” King was still plenty competitive, but as she had when she got her first glimpse of Evert, she recognized a player with the potential to take the women’s tour to new heights.

“But,” added Billie Jean, “if you don’t work hard you are not going to make it.” That was the problem. Navratilova defected from Czechoslovakia in 1975, and everything about the move conspired against her tennis. She was on her own at 19, cut off from a once-close family. In the United States, she suddenly had everything she could dream of. There was no pressing need to fight to improve her game.

Talent was enough to earn Martina her first two Wimbledon titles, in 1978 and 1979. On her day, she was unbeatable. But then, even more than today, the tour was a year-round slog. Questionable fitness and a topsy-turvy personal life made her susceptible to human backboards like Evert and Tracy Austin.

Nancy Lieberman, the basketball star who would soon change Navratilova’s outlook, recognized what was missing. “I could see,” Lieberman said, “that Chris Evert wanted to win and Martina just wanted to play.”

* * *

The arrival of Lieberman marked a turning point for Navratilova’s career. The women met at the Amelia Island tournament in 1981. Evert beat Martina there on the clay, 6-0, 6-0, but Lieberman quickly cottoned on to her new friend’s astonishing gifts.

Seven years earlier, Billie Jean had said that the left-hander could be the best. Lieberman told Martina that she should become the greatest of all time.

The hoopster quickly became a familiar face at Navratilova matches. She took the role of a full-time fitness coach and motivator. Martina both slimmed down and gained muscle. Gym work was rare among women players of the time; competitive as Chrissie was, she hesitated to compromise her femininity. Navratilova had Lieberman’s persuasive voice in her ear, and she didn’t have a reputation as America’s princess to protect.

The same year, Martina added her first full-time coach: Renée Richards. The transgender Richards had competed as a man before undergoing surgery and making headlines on the women’s tour. Navratilova rarely shied away from controversy, and another distraction hardly registered at this point; she had recently been outed as gay by a New York newspaper. While fans and media fixated on the growing entourage of outsiders, Richards added the technical and tactical acumen that Navratilova’s game had been missing.

“I couldn’t believe how little Martina knew about playing tennis and how faulty her strokes were,” Richards told Johnette Howard. (How great an athlete was she? This is a two-time Wimbledon champion we’re talking about here!) Navratilova’s first tournament with Richards at her side ended in disappointment, as she failed to put away Austin in a three-set final at the 1981 US Open. But she had beaten Evert in the semis to get there, and she upset her rival again at the Australian a few months later.

Stronger, sturdier, and savvier, Martina was ready to ascend to a higher plane of tennis dominance.

* * *

1982: 15 titles in 18 events. Evert lost to Jaeger at Roland Garros, and Navratilova took advantage to win the French for the first time.

Commentator Mary Carillo said, “Martina went from somebody who got nervous and thought, ‘I can be up a set and a break and still lose’ to someone who thought, ‘This shouldn’t take more than forty-five minutes.'”

1983: 86-1. Martina lost early at the French, and that was it. She completed her career Grand Slam at the US Open. Across seven matches in New York, she lost only 19 games.

“I try to… uphold women’s tennis,” said Shriver, “and say that the other players aren’t that far behind, when, in fact–at least at the majors–we’re light-years behind.”

Mike Estep took over for Richards this season as Navratilova’s coach. Martina was already the most aggressive player on the circuit, and Estep encouraged her to go even bigger, attacking at every opportunity. “You’re not trying to be number one,” he told her. “Your goals are beyond that.”

1984: 74 wins in a row. Hana Mandlíková scored an upset in Oakland to start the season. Navratilova reeled off 13 straight tournaments before finally dropping another decision to Helena Suková in Australia. Oh, and she paired with Shriver to win the doubles Grand Slam.

“It’s hard playing against a man–I mean, Martina,” said Mandlíková. “She comes to the net and scares you with those big muscles. She is very big and difficult to pass.”

For the record, the “very big” Navratilova was five feet, eight inches tall. Hana was–let me check my notes here–five feet, eight inches tall. Martina was difficult to pass both with and without the scary muscles. The young Czech eventually apologized.

1985: Another 84 match wins and, for the first time, the singles final at all four majors. Chrissie had rededicated herself to catching Navratilova, and Martina still won four of six meetings.

“It’s really strange what Martina’s play has done to the women’s tour,” said Billie Jean King. “Everyone seems so paranoid to walk on the court with her.”

1986: 89-3. Three more singles finals in three majors, continuing a streak that would eventually run to 11 straight slams. The cast of characters was changing, but the 29-year-old Navratilova continued to hold sway. She won three of four meetings with Steffi Graf, four of four against Gabriela Sabatini, and two of three over Evert for good measure.

“She seems a freak of nature,” said Virginia Wade, “the perfect tennis player.”

* * *

Any one of those seasons would have earned Martina a place in tennis history. Five of them together was unthinkable.

Estep often told her, “A good attacking player will beat a good baseliner almost all the time.” Navratilova went out and proved it.

The field–led by Graf–slowly caught up, but not without revealing the depth of Martina’s transformation. In the 1970s, she had all too often played brilliant tennis and lost. By the 1990s, she couldn’t always summon the speed and the reach of her younger self, but she kept winning anyway.

She did, in fact, turn in a flawless performance to win her record-setting ninth Wimbledon title in 1990. But that was secondary. “I didn’t care if I scraped and scratched to get this,” she said after beating Zina Garrison in the final. “They don’t put an asterisk next to your name saying you won but didn’t play that well.”

No, there are no asterisks on Navratilova’s record. Not on her 43 wins over Evert. Not on her seven defeats of Monica Seles, who was a teenager as Martina persisted into her thirties. Not on her Australian Open mixed doubles title in 2003, the championship that completed her career Grand Slam in all three disciplines.

Back in 1978, the left-hander finished the year atop the WTA rankings for the first time. After a hard-fought season, though, her status was insecure. Many pundits overruled the computer and rated Evert higher. Martina didn’t care for the uncertainty. “I want to be number one in the mind of every single person on this earth,” she said.

It didn’t happen immediately. It took a complete mental and physical overhaul. But for five full years, that’s exactly what she was.

* * *

Previous: No. 4, Novak Djokovic

Next: No. 2, Steffi Graf

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: