Alright, alright, alright.

When I started writing these player-themed pieces more than a year ago, Jessica Pegula was at the top of my list. One of my goals is to demystify the factors that cause each player’s success, or lack thereof. Pegula has had plenty of success, but compared to her peers at the top of the game, it is difficult to say exactly why.

There’s no obvious calling card that intimidates opponents. Pegula doesn’t serve very hard, ranking in the middle of the pack at least year’s US Open with an average serve speed around 92mph and first serves at 99mph. She doesn’t hit many aces. She ranks just outside the top ten in hold percentage, largely because she cleans up on second serves. That’s her one standout, top-line stat: In the 52 weeks leading up to Indian Wells, she won 51% of second-serve points. Only four women have topped 50%, and only Iga Swiatek wins more.

Pegula’s return numbers are even more anonymous. She ranks 20th among the WTA top 50 in break percentage. Top 20 on both sides of the ball is outstanding and unusual, but again, hardly intimidating. Whether serving or returning, she isn’t particularly effective on break points. Not that she’s bad in that department, but clutch play doesn’t help us understand all the match wins.

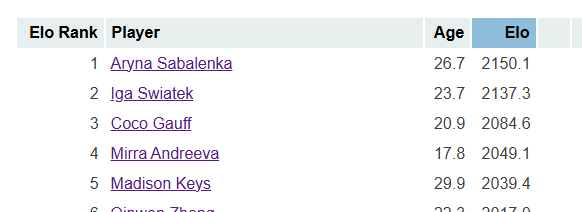

But win matches she certainly does. The American has held a place in the top ten since June 2022, much of that time in the top five. She has won seven tour-level titles and reached finals at both the US Open and the year-end championships. Off a title in Austin, she’s on a seven-match winning streak going into today’s match against Elina Svitolina. Elo isn’t quite as excited about her performance, but even that metric places her seventh, only 16 points behind fifth-place Qinwen Zheng.

What, then, is Pegula doing so right? When a player gets better results than her tools seem to suggest, I tend to fall back on difficult-to-quantify assets like movement, anticipation, and the blackest box of all, tennis IQ. Pegula excels in all those categories. But can we do better?

Second thoughts

Let’s start with the second serves. Here’s a generic theory for you: second-serve win percentages are related to success rates on return. Few women have dominant second serves–remember that Pegula is one of only a handful who win more than half of those points–so especially if the returner puts the ball in play, the server is already on defense.

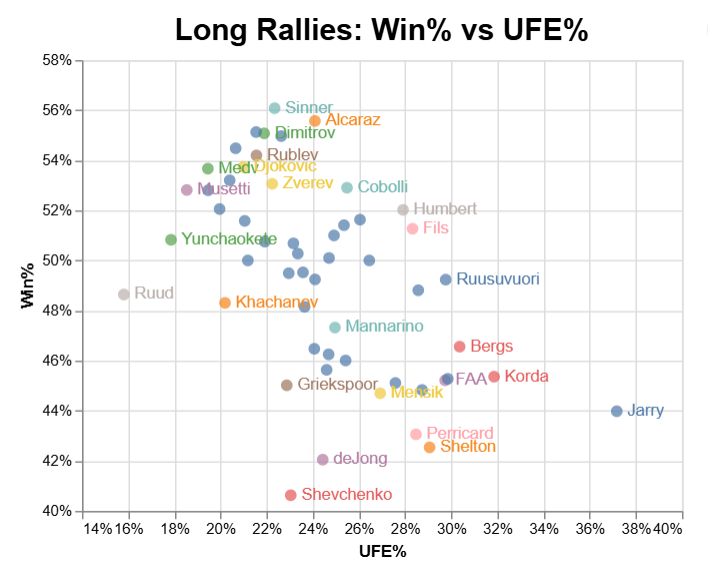

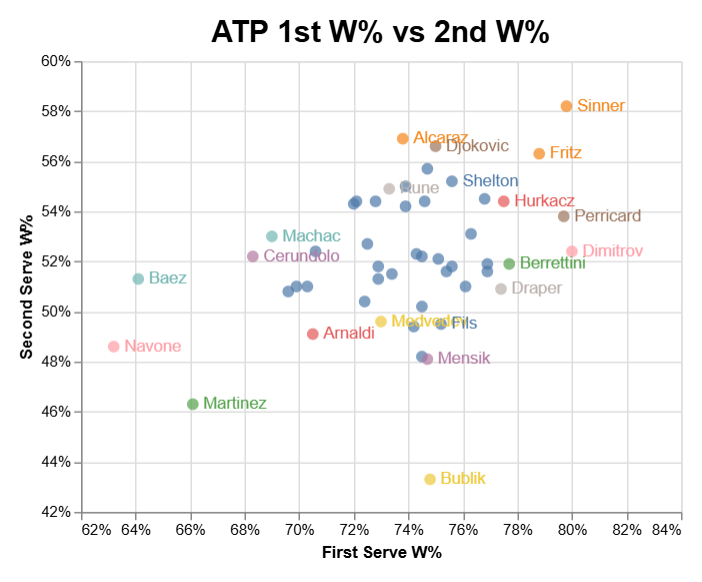

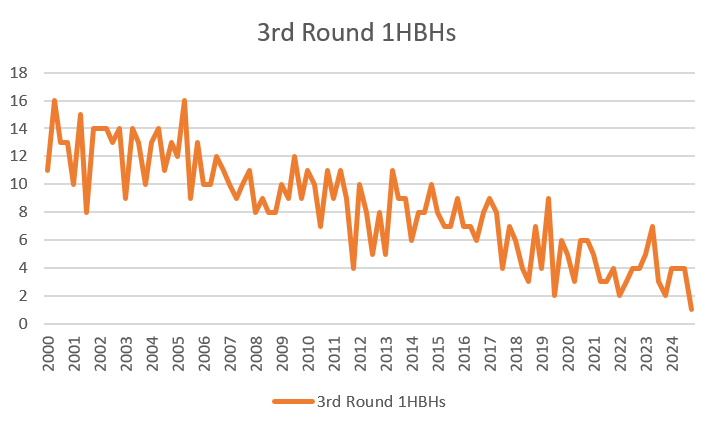

Indeed, there’s something of a relationship, though not a statistically strong one. This plot shows the WTA top 50 in both categories:

Here’s a sentence I didn’t expect to write: Pegula and Sabalenka are almost identical in this pair of metrics. To go a step further, the cluster of players extending from Alexandrova in the lower left, to Sabalenka, then to Swiatek in the upper right, is disproportionately made up of big hitters. (The finesse players, along with the always unpredictable Jelena Ostapenko, are in the lower right.)

Yet by the standards of women’s tennis in the 2020s, Pegula is not a big hitter. It’s natural enough that she would equal Sabalenka’s return results, even if they get there in different ways. But second serves, too?

After watching Pegula’s quick dismissal of Xinyu Wang on Sunday, I thought I had the answer. While her second serves aren’t fast (79mph on average at last year’s US Open), they are precise. She doesn’t tee them up down the middle, and she manages to hit targets close to the service line. Location can be as valuable as raw speed, so that might explain how she gets the results of a bigger server.

Except… I can’t prove that she does any of that on a consistent basis. US Open scorers classify serve depth as “close to the line” or “not close to the line. Pegula merited a “close to the line” designation on 15% of her second serves, compared to a tournament average of 18%. She was slightly below average on first serves, too.

As for serve direction, it’s the same story. The Match Charting Project classifies each serve as one of three directions: wide, body, or down-the-tee. The average server hits one of the corners (wide or tee) with about 80% of their second serves. Pegula’s number is 74%. That’s not in itself bad–Venus Williams sports the same number–but it certainly doesn’t support my theory.

If there’s a quantifiable reason why Pegula wins all those second-serve points, it doesn’t look like we’ll find it in the second serve itself.

The match and the territory

Another eye-test hypothesis about Pegula: She doesn’t wait for the game to come to her. She stands as close to the baseline as she can get away with, both returning serve and in rallies. She doesn’t back up when faced with a deep drive or a high bounce. Depending on the shot, she’ll pick it up on a short hop or reach above her shoulder.

Not everyone is able to do this. For those who can, the advantages are clear. The earlier you hit the ball, the faster it gets back in your opponent’s court–and the less time they have to react. It’s power tennis for women without overwhelming power.

This style of play is particularly effective against opponents who aren’t particularly aggressive. Pegula’s losses this year have come against Madison Keys, Olga Danilovic, Ekaterina Alexandrova, and Linda Noskova: a quartet of heavy hitters who end points fast. Pegula lost just two matches on North American hard courts last summer, both to Aryna Sabalenka.

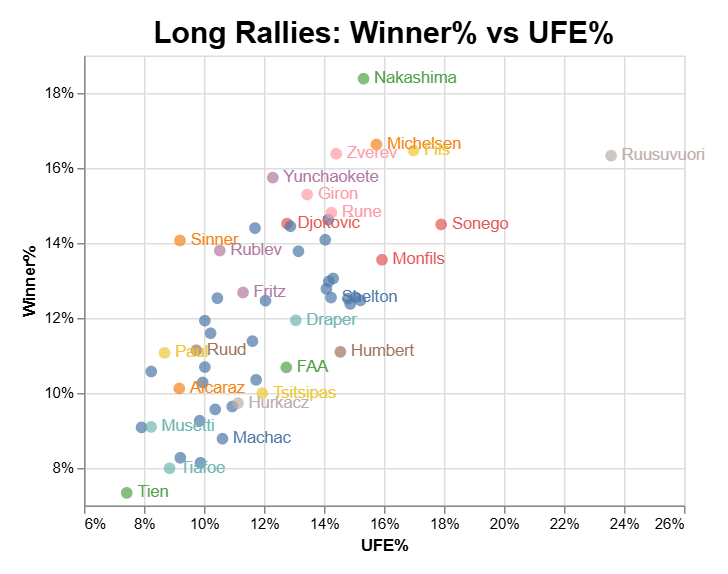

Against less free-swinging foes, the American takes away chances. Pegula doesn’t hit an overwhelming number of winners: 6% of her groundstrokes go untouched, in line with tour average. But her opponents do worse. In the Austin final, McCartney Kessler scored winners on just 2% of her shots from the baseline, half her usual rate. Pegula applied the same pressure to Xinyu Wang Sunday, slashing the Chinese player’s groundstroke-winner rate to 4% from a career average of 7%.

Again, these are stats that invoke parallels with a different style of player. The best way to prevent winners is to hit winners of your own, or at least end the point trying. That’s the Keys/Alexandrova/Ostapenko/etc playbook. Yet by Aggression Score, a metric that puts those ball-bashers on top, Pegula is below average, keeping company with the likes of Emma Navarro and Mirra Andreeva.

Deep research

Maybe you’re convinced that this explains a lot of Pegula’s success. She hugs the baseline, cuts off angles, and takes away opportunities for all but the most aggressive players to find openings of their own.

Still, I’d like more support from the numbers. Positioning is tricky to quantify, so I want to focus on one specific situation. What happens when the American is faced with a very deep service return?

Deep returns essentially erase the server’s advantage, neutralizing the point with one swing. The server usually needs to take a step or two back, and unless it’s a perpetual gambler like Ostapenko, she won’t try anything flashy for at least one more shot. Pegula doesn’t aim to end the point, either, but she’s less likely to concede territory. While that doesn’t allow her to seize the advantage, she’s careful not to hand too much of an edge to the returner.

Yet… nope. The next table shows how the ten players with the most hard-court data since 2022 handle deep second-serve returns: How often they get the next ball back in play (“3rd-inPlay”), how often those balls in play result in points won (“inPlay W%”), and how often they win points against deep returns, even considering the ones they didn’t get back (“vsDeep W%”).

Player 3rd-inPlay inPlay W% vsDeep W% Iga Swiatek 84.2% 59.8% 50.4% Aryna Sabalenka 77.5% 63.5% 49.2% Karolina Muchova 84.2% 56.3% 47.4% Paula Badosa 84.2% 54.6% 45.9% Elena Rybakina 79.5% 57.5% 45.7% Daria Kasatkina 85.5% 52.2% 44.6% Coco Gauff 83.6% 53.2% 44.5% Jasmine Paolini 82.7% 53.7% 44.4% Jessica Pegula 81.9% 53.2% 43.6% AVERAGE 81.8% 53.0% 43.4% Qinwen Zheng 76.5% 52.6% 40.2%

Pegula is almost exactly average, which makes her less effective against deep second-serve returns than most other top players. (The average considers all players, not just those listed, which is why it’s so close to the bottom.) Sticking to the baseline might still be the best solution for her, but it doesn’t win her an unusually high number of points.

This is a lot of negative results for one post. Pegula is close to the best in the business at turning her second serve into points won. But it’s not because she hits her seconds deep, or because she keeps the ball away the returner, or because she handles deep returns unusually well.

So we’re more or less back where we started. The American does a lot of things well, or at least well enough that they are not liabilities. Among top 50 players, she is average or better in nearly every category, close to the top ten in a few. By my groundstroke potency metrics, FHP and BHP, she does even better: She ranks among the top 20 in both, one of the few players to do so.

That, apparently, is good enough for a place in the top five. With better, finer-grained stats, we might be able to isolate how Pegula turns court position into victory. For now, we can appreciate how she holds her own against opponents with more fearsome weapons. Her personal brand of flexible shotmaking is certainly working, whether we understand it or not.

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: