South Africa was a problem. Many world leaders were quick to condemn the racist policies of the apartheid government. Less clear was what exactly to do about it. As always, international sporting events fell in the crosshairs.

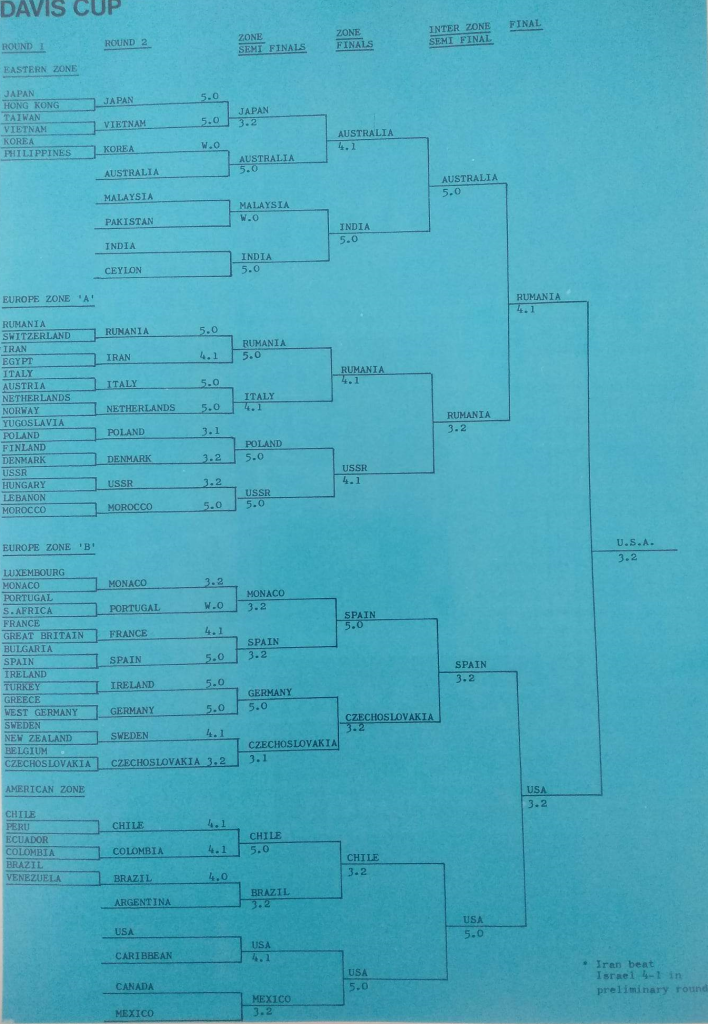

Eastern Bloc nations were willing to sacrifice the most. In 1968 Davis Cup play, South Africa advanced to the final of the European Zone when Romania gave them a walkover. (There was no separate Africa zone, and “zoneless” nations were free to choose another region in which to compete.) In 1969, both Poland and Czechoslovakia refused to play them. In 1970, South Africa was banned from the competition altogether.

There was never a consensus to exclude the country, and South Africa returned to competition in 1973. It chose to enter the South American zone, where the political ramifications were likely to be the least. Conveniently enough, the competition wasn’t particularly strong, either. In March, South Africa brushed aside Uruguay while Argentina defeated Brazil, setting up a zonal semi-final between the two, set to be hosted in Argentina.

The Argentines found themselves in a sticky situation. The federation had anticipated no problems; golf and rugby teams from South Africa had visited in the previous two years. But Davis Cup was one of the biggest events on the global sporting calendar, and the public outcry couldn’t be ignored. If the tie were played in Argentina, there would be protests, possibly substantial ones. On the other hand, it was unthinkable to forfeit the round, as the Eastern Europeans had done. Thanks in large part to charismatic 20-year-old star Guillermo Vilas, the tennis boom had reached Argentina. If they could get past the South Africans, Argentina would face regional rival Chile in the zonal final and push the sport’s popularity to even higher peaks.

It’s difficult to overstate just how much the South African issue roiled international sports. Arguably, it was an even more prominent, divisive issue than the fate of Russian and Belarussian athletes in 2023. The same week that Argentina’s tennis federation made its final preparations, New Zealand Prime Minister Norman Kirk settled a long-standing dispute by barring a visit from the South African rugby team. “Arguments over the tour,” wrote the New York Times, “have continued more than two years, spilling over party and racial boundaries and far eclipsing such international issues as the Vietnam War.”

Back in Argentina, the federation, pressured by the country’s Foreign Ministry, settled on a compromise. The tie would be held in Montevideo, just across the border in Uruguay. And to keep publicity down even further, the dates would be moved up by a month, from mid-May to mid-April. Once again, politics served as a cover for a bit of gamesmanship. Fiddling with the dates would keep South African standouts Cliff Drysdale, Bob Hewitt, and Frew McMillan on the sidelines. All three were committed to the World Championship Tennis circuit and couldn’t accommodate the revised schedule.

On April 13th, at the Carrasco Lawn Tennis Club, the sides could finally get down to business. With the WCT stars out of commission, the inexperienced Argentinian squad faced an even greener South African squad. In the first rubber, Argentina’s Julián Ganzábal held off doubles specialist Pat Cramer 6-2, 6-0, 3-6, 6-0. In the second, Vilas shut down 18-year-old Bernard Mitton in straight sets.

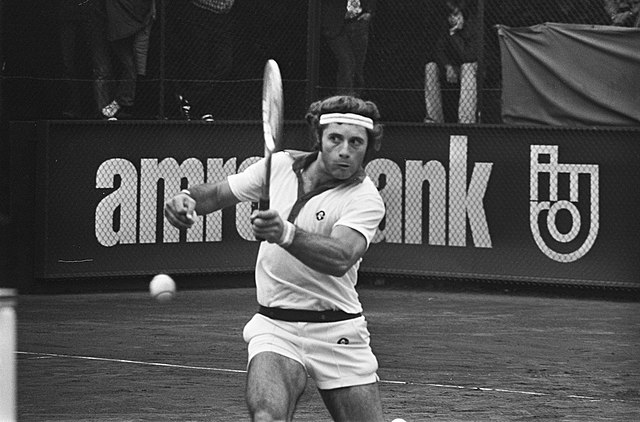

Vilas was far from the superstar he would later become, but the left-hander’s potential was becoming clear. He had reached finals in Cincinnati and Buenos Aires the previous year, and the Mitton match was his fifth straight victory of Argentina’s 1973 Davis Cup campaign. On the slow clay of the Carrasco Club, he may well have beaten Drysdale or McMillan, too.

But he didn’t have to. After the South Africans won the doubles on day two–the country was second only to Australia in its ability to churn out top-tier doubles players–Vilas made quick work of another teenager, Deon Joubert. Argentina’s top player lost just five games in three sets.

The international tennis community breathed a collective sigh of relief. Fractures were everywhere: The same day that the South Africans were eliminated, a spokesman for the International Lawn Tennis Federation threatened to suspend the women of the Virginia Slims tour if they continued to defy their national federations. Had Argentina lost, the Marxist government in Chile may well have forced its side to forfeit the zonal final. South Africa would have advanced to a bigger stage and the controversy would have multiplied.

Vilas hardly solved the South Africa problem, but he did punt it one year down the road. In the political and bureaucratic mess that was tennis in 1973, that counted as a major victory.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: