The Federation Cup barely registered on the packed tennis calendar. The international women’s team competition was still relatively new: The ILTF launched it in 1963. The arrival of the Open era almost immediately shunted it to second-tier status, as the game’s stars increasingly focused on prize money, none of which was available here.

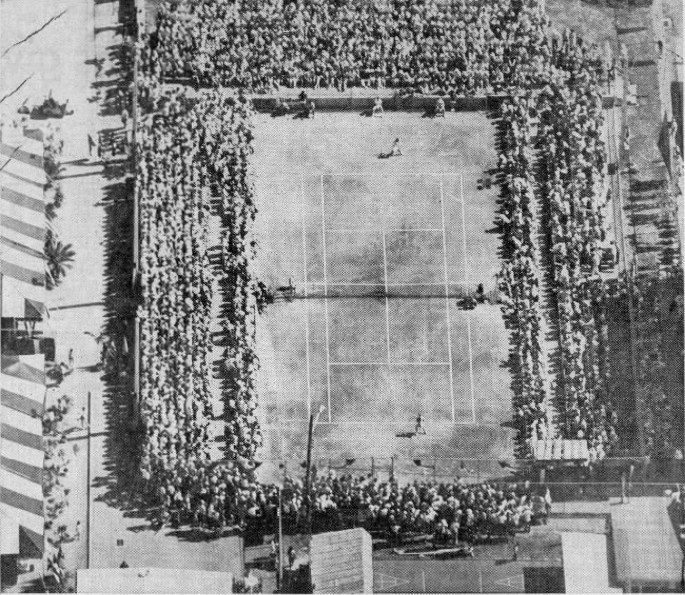

1973 couldn’t have driven the point home any more clearly. At the same time that women’s teams from South Africa to Norway to Korea competed for the Cup, $100,000 was at stake in Hilton Head, South Carolina. Needless to say, plenty of stars were missing at the quaint, old-world club in Bad Homburg, Germany where the one-week event was held.

Virginia Wade, however, was always ready to wear the colors. She had played every installment of Federation Cup since 1967. She led the British squad to runner-up finishes in each of the previous two years, falling to the hosts–Australia in 1971, South Africa in 1972–each time. Aside from another Cup stalwart, Evonne Goolagong, Wade was the best player there.

She had extra motivation, as well. The British team was well-financed, with cash prizes for players who recorded wins. The arrangement was not entirely novel, but the fact that it became public–even discreetly–was rare.

The Brits knew there were no guarantees, especially if it came down to a final against Goolagong and the Aussies. But Wade’s side had never, in a decade of Federation Cup play, failed to reach the semi-finals. With so much top-tier talent missing, anything less was unacceptable.

The 30-country field was whittled down to eight in a just a few days of best-of-three-match ties. Two nations didn’t play at all: Poland refused to compete because of South Africa’s participation, and Chile’s team didn’t show up at all. (It’s possible they stayed home for the same reason.) There were few early surprises. The United States needed a deciding doubles rubber after an unknown Korean named Jeong Soon Yang upset Patti Hogan. But the Americans weren’t expected to make a deep run anyway: The four-time champions were missing a football team’s worth of stars. Billie Jean King, Rosie Casals, and Nancy Gunter were at Hilton Head, and Chris Evert was finishing her senior year of high school.

On May 4th, Great Britain took on Romania in the quarter-finals. Romania was well-known for its exploits in the men’s game: Ilie Năstase was arguably the best player in the world, and with Ion Țiriac, he had made his country a perennial Davis Cup contender. The women had no such résumé. Veteran Judith Gohn was no threat against someone like Wade, and unknowns Mariana Simionescu and Virginia Ruzici were 16 and 18 years old, respectively.

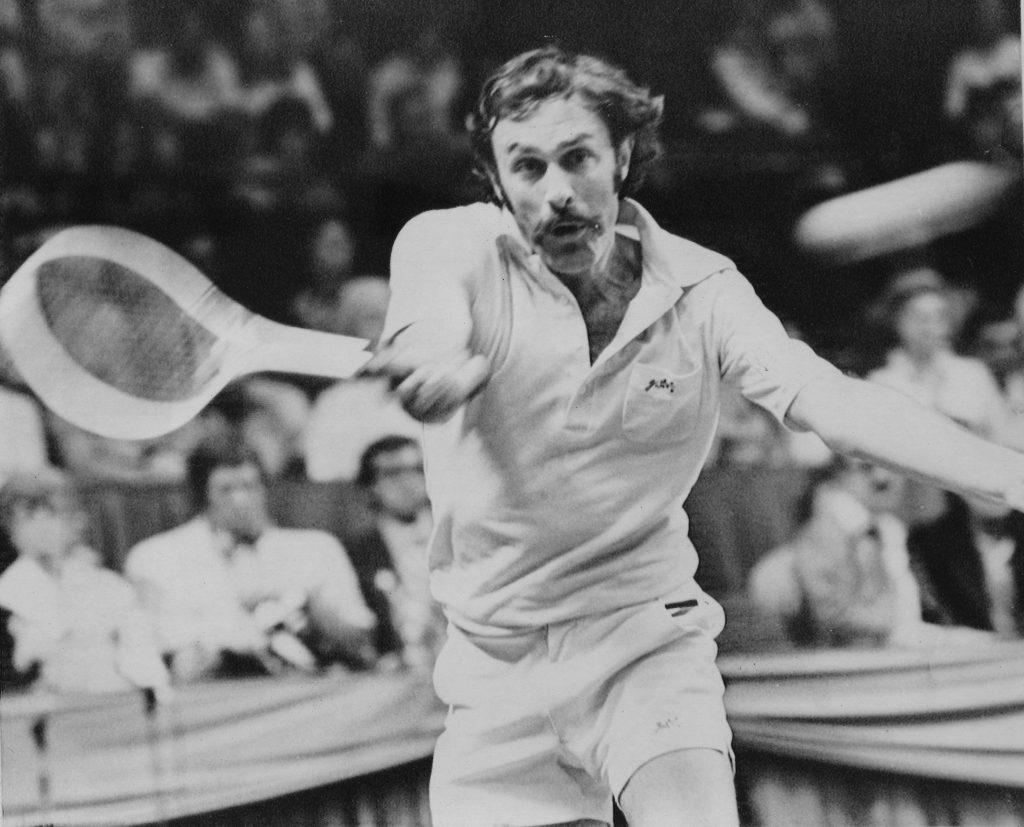

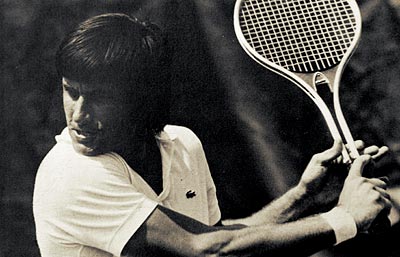

Simionescu (left) and Evert in 1980, when both were married to fellow tennis pros

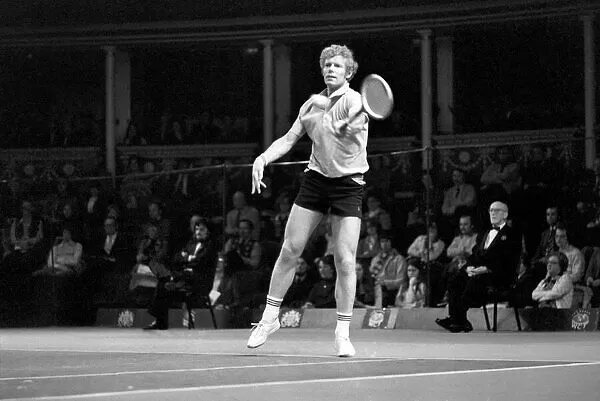

Wade dispatched Gohn with ease, handing off the baton to Joyce (Barclay) Williams, a 28-year-old Scot who had reached the quarter-finals of the US Open two years earlier. Alas, the British number two had no way of preparing for this crucial rubber. Lance Tingay captured the youthful verve of Simionescu:

She exploded into action, this strong, jolly lass of only 16, who laughed when she hit winners, laughed when she had winners hit against her and laughed when she fell over. And what fine winners hers were!

Simionescu’s forehand was “forked lightning,” the best weapon off that wing of any of the women in Bad Homburg. While she was every bit as inconsistent as you’d expect of a hard-hitting, inexperienced teen, she pulled out the victory, 6-3, 6-8, 6-3.

That left the stage open for Virginia Ruzici. Veteran journalist David Gray, who sang Simionescu’s praises nearly as heartily as Tingay did, judged Ruzici to be even more talented. The Romanians played as if they had nothing to lose, and the attack of Gohn and Ruzici snatched the deciding doubles rubber from Wade and Williams, 7-5, 6-2.

More than anything else, the British defeat was a reminder that women’s tennis was–finally–truly global. A dozen years earlier, the only international women’s competition was the Wightman Cup, which pitted the Brits against a United States squad each year. Now there were 28 more nations to contend with, most of them outside the Anglosphere. Romania hardly had a presence in the women’s game just a few years earlier; now they were two rounds away from a Federation Cup title.

This being 1973, though, it wasn’t that simple. Romania, like Poland, objected to the inclusion of South Africa in international sporting competitions. All of the sudden, the surprise victory against the UK set up a semi-final against South Africa. The Romanian coach had instructions from the upper reaches of his government to default such a tie if it arose. The country’s Davis Cup team had done so just five years earlier.

ILTF and federation officials spent the rest of the day in a flurry of diplomacy. For five hours, phone calls and telegrams bounced back and forth between Bad Homburg and Bucharest. The semi-final was rescheduled from Saturday morning to Saturday afternoon to give the negotiations more time. At last, the Romanians agreed to play. The potential for glory was, at least this time, on this stage, greater than the implicit approval of the apartheid regime.

The unexpected political brouhaha had at least one positive effect: It pushed the British loss out of the UK papers. No one was happy about the early exit, but it was easy to forget. This was, after all, just the Federation Cup. There were bigger events in tennis happening around the world, and the next two months would bring a crop of exploits and controversies guaranteed to keep British tennis fans focused elsewhere.

* * *

This post is part of my series about the 1973 season, Battles, Boycotts, and Breakouts. Keep up with the project by checking the TennisAbstract.com front page, which shows an up-to-date Table of Contents after I post each installment.

You can also subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: